This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1839 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

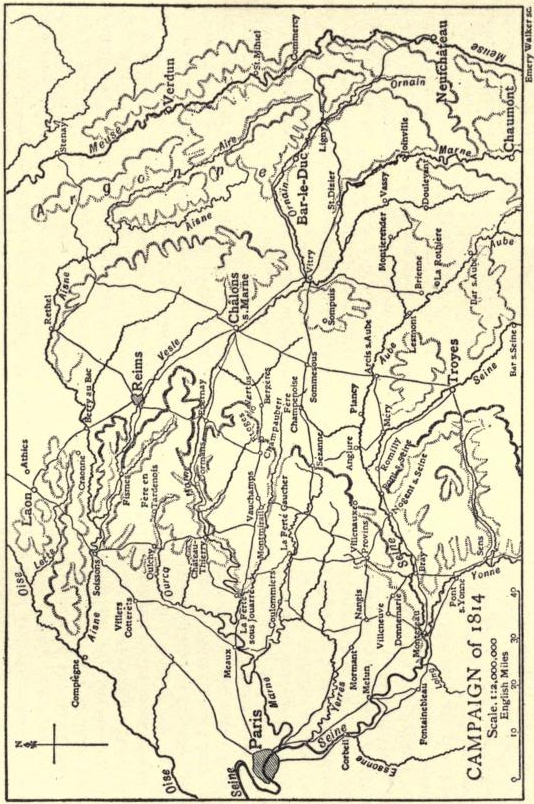

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

HISTORY OF THE CAMPAIGN IN FRANCE, IN THE YEAR 1814

TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN

BY

A. MIKHAILOFSKY-DANILEFSKY

Aide-de-Camp and Private Secretary of the late Emperor Alexander.

ILLUSTRATED BY

Plans and Maps of the Operations of the Army.

NOTICE.

THE original Work, from which the present volume has been translated, was published in St. Petersburg during the latter part of the year 1836. The Author, a well-known Russian General, is now a Member of the Imperial Senate.

During the eventful campaign of 1814, he served as Aide-de-camp to the Emperor Alexander, and was constantly at His Majestys headquarters, where he was employed in wielding both the sword and the pen.

Although the Translator has not the pleasure of being personally acquainted with the Author, yet he had ample opportunities of learning, from other distinguished Russian officers, who were high in command during the war in France, their very favourable opinion of the merits of his work, both for its accuracy and impartiality.

RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN IN FRANCE.

CHAPTER I.

General view of the CampaignPosition of Affairs on the Opening of the Campaign of 1814The Designs of the Emperor AlexanderCondition of the AlliesThe Allied ForcesState of the French ArmyThe Russian ForcesConduct and Views of the Emperor Alexander.

Russia had already celebrated, before the beginning of the year 1814, the anniversary of her deliverance from foreign invasion, with the appointed religious solemnities and public rejoicings. The grass had again waved green on the fields of Borodino, Taroo-Vino, and Krasnoy, and, from the Moskva to the Niemen, towns and villages had risen from their ashes. Our country had revived with a fresh and vigorous life, and our sovereign, the acknowledged liberator of Europe, was at the head of his victorious legions on the banks of the Rhine. Austria, Prussia, the German Princes, Holland, Spain and Portugal, had thrown off the yoke of Napoleon, who was now engaged in negotiating with the Pope and Ferdinand VII. the terms of their re-establishment on their respective thrones. His near relation, the King of Naples, was only waiting for a favourable moment to take up arms against him. England having renewed her friendly relations with the continental powers, the flags of all nations were again unfurled on seas, on which, during the long period of ten years, not even the peaceful merchantman had ventured to set a sail. To ensure the general tranquillity of nations, there needed but to place an insurmountable barrier to the ambition of Napoleon, and that could only be done by crossing the frontiers of France.

The campaign of 1814 ought not to be considered as a new war, but simply as the continuation of the campaign of 1813, which the Emperor Alexander had opened single-handed, and in which he was afterwards joined by the other powers, in the hope of regaining their independence. The victory of Leipzig brought the Allies to the Rhine, but did not put an end to the war. The negotiations at Frankfort failed of success, for this plain reason,that neither side brought anything like sincerity to the discussion. Alexander warmly insisted on the necessity of continuing the contest, and exerted himself to infuse the same spirit into his allies, some of whom were satisfied with seeing the French driven out of Germany, and pretended that the object of the treaties of offence and defence had been gained, and that Napoleon, forced across the Rhine, was no longer in a condition to trouble the peace of Europe. The Emperor at last succeeded in bringing over the Allies to his opinion, and in getting them to adopt the plan of operations which he had traced; in short, it was finally resolved to invade France, and by penetrating into the heart of that country, to oblige Napoleon to accept of such terms as should re-establish and secure the political balance of Europe.

Napoleon was still the recognised ruler of France, and it is certain that at this time the Cabinets had not the slightest idea of wresting the sceptre from his grasp, and of handing it over to the representative of the Bourbons, who was residing in England as a private gentleman. On the occurrence of any important event, the latter would take occasion to remind the Allies, by letter, of his right to inherit the throne of his ancestors, and when they approached the Rhine, he requested them to proclaim his legitimate authority; but no attention was paid to his wishes. His brother, the Count d Artois, with his two sons, was now on the point of leaving London for the Continent, in order to be nearer to the theatre of war, but not one of the allied monarchs entered into treaty with the Bourbons, or flattered them with promises. Yet in the bosom of him, who was the soul of the Alliance, there already lurked the intention of dispossessing Napoleon,an intention, which though not manifested by any overt act, was no secret to two or three persons, who enjoyed his confidence. Still a sharp-sighted observer might, in some measure, guess the colour of his thoughts from the following maxim, which Alexander, as he drew near the frontiers of France, and indeed during the whole course of the war in that country, frequently repeated, both verbally and in writing, and to which he steadily adhered: We should make the march of political arrangements depend on the success of our arms, and not fetter ourselves with any premature engagements; we should look to victory for the most advantageous conditions of a general peace.

Napoleons reflections had led him to precisely the same conclusion, and he acted accordingly. He was not shaken by the successive blows which had annihilated his armies in Russia and Germany. He bore his defeats with firmness, and, on his return from Leipzig, gave his exclusive attention to the assembling of fresh troops, to oppose the general armament against him. He used the utmost activity in the formation of his armies, and tried, by every means, to render the war national. In neither of these attempts, however, was he cordially seconded by the wishes of France, where all ranks were calling out for peace. The reflection of that military glory, with which Napoleon had dazzled France, was now felt to be a feeble compensation for the decay of agriculture and manufactures, the stagnation of trade, the conscription, the loss of husbands and fathers, and heavy taxes. But Napoleon heeded the voice of his suffering people as little as he did the counsels of his friends and the representatives of those public functionaries, who, after years of silence, now ventured to speak out their sentiments on the ruined condition of the empire, and the absolute necessity of peace. The child of victory turned a deaf ear to their respectful remonstrances, and told his advisers that he could not sit on a throne whose lustre was tarnished, nor wear a crown which was shorn of its glory. Inveighing against despondency, he exerted himself to rekindle the warlike ardour of the nation, and to rouse the spirits of his troops to a contest in which he hoped to regain the glory he had lost, and consequently that preponderance in the affairs of Europe which he had once enjoyed. In these circumstances, reconciliation was far off; indeed it was equally distant from the thoughts of Alexander and of Napoleon.