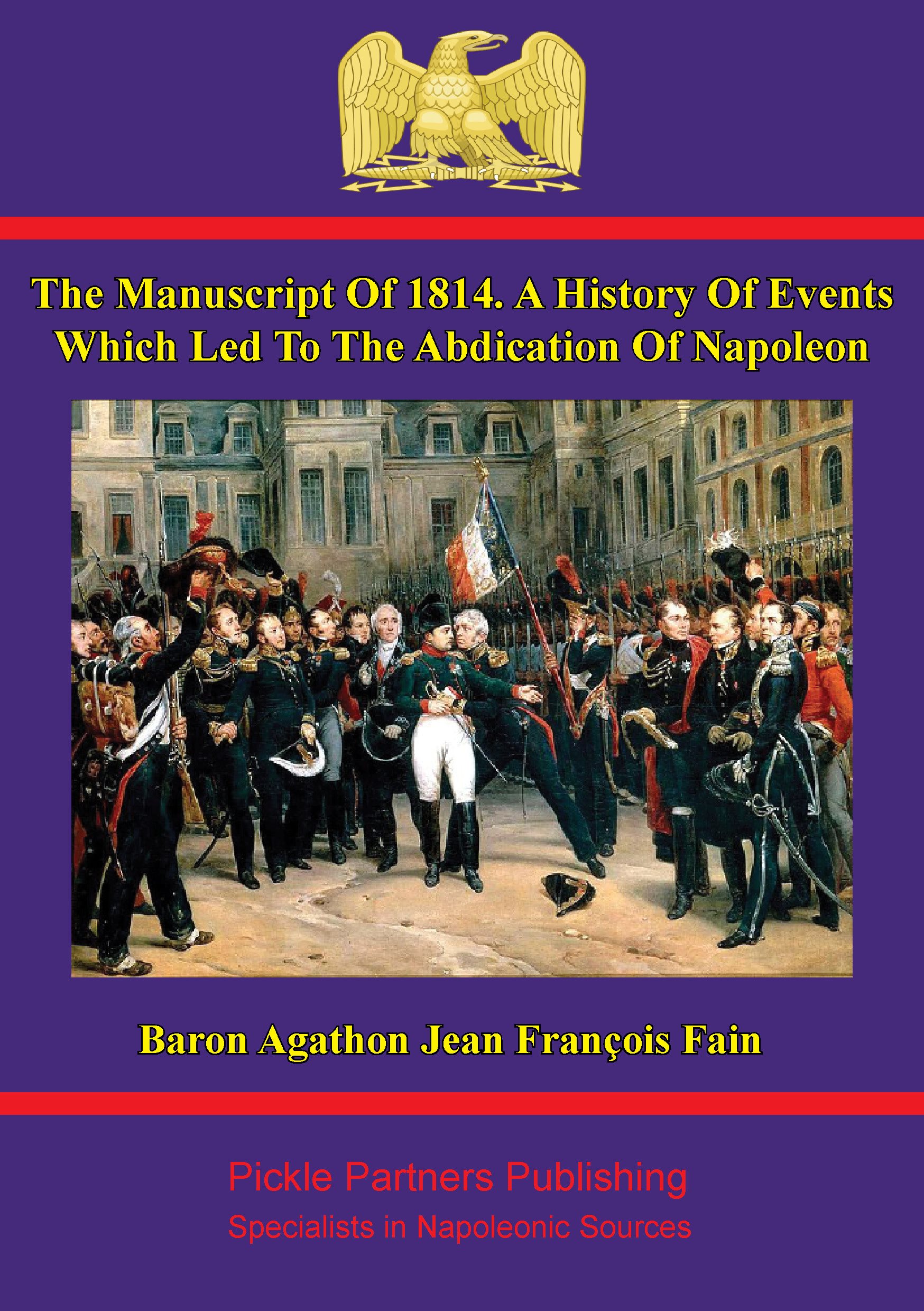

This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books contact@picklepartnerspublishing.com

Text originally published in 1823 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2013, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

MEMOIRS OF THE INVASION OF FRANCE

BY THE ALLIED ARMIES, AND OF THE LAST SIX MONTHS OF THE REIGN OF NAPOLEON, INCLUDING HIS ABDICATION.

WRITTEN AT THE COMMAND OF THE EMPEROR,

BY BARON FAIN,

FIRST SECRETARY OF THE CABINET.

NEW EDITION.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

MANUSCRIPT OF EIGHTEEN HUNDRED AND FOURTEEN.

PART I.NAPOLEON IN PARIS. (FROM THE 9th OF NOVEMBER, 1813, TO THE 24th JANUARY FOLLOWING.)

CHAPTER I.NAPOLEONS ARRIVAL IN PARIS.THE FIRST MEASURES HE ADOPTED. (November, 1813.)

Germany was lost; nothing now remained but to save France or to fall with her.

Napoleon returned to Paris on the 9th of November, 1813; and he exerted every effort to turn his remaining resources to the best account.

The first words he addressed to the senate were:A year ago all Europe was marching with us; now all Europe is marching against us.

A decree was immediately issued for levying three hundred thousand men.

Engineers were ordered to proceed to the roads and fortresses of the north, with directions to restore the old walls which were formerly the ramparts of France; to lay out redoubts on the heights, to serve as rallying points in our retreats; to fortify the defiles in which national courage might oppose the enemys passage; and finally to make every preparation for cutting the dykes and bridges which it would be necessary to abandon.

Orders were issued to the depots for remounting the cavalry, to the cannon foundries, the manufactories of arms, the clothing warehouses, &c.

But money was wanting; the treasury was exhausted. Napoleon had recourse to his private funds. In vain was it proposed that these funds should be set aside, as private deposits which might secure the different members of the Imperial family against the reverses with which they were threatened. This advice was rejected as being of too personal a nature, and the Baron de La Bouillerie, the crown treasurer, was directed to transfer thirty millions in crowns from the private to the public treasury. Thus public credit, and every branch of the public service resumed its wonted activity.

Councils of administration, of war, and of finance, succeeded each other hourly at the Tuileries. The days were too short for the business which it was necessary to transact. But Napoleon availed himself of the night, and employed the hours which should have been devoted to rest, in reading what his ministers had not had time to tell him, in signing the documents which had not been dispatched in the day, and in deliberating on his plans.

The army of Germany had just returned within the limits of the French territory, by the bridges of Mentz. It was necessary to assign to it a position where the troops might enjoy the repose of which they stood in need. This army now formed behind the Rhine, a line, which was every day extending, and which was soon to be prolonged from Hningen to the sands of Holland; but the exhausted state of our troops and magazines afforded no ground to hope for maintaining the defence of so extended a line. Those who considered the question merely in a military point of view, became alarmed at the idea of our forces being dispersed. We could not seriously think of defending the Rhine, and therefore, it was said, we ought immediately to abandon it. But Napoleon was guided by other considerations: We were weak, but our weakness was a secret which it was necessary should be kept as long as possible. The Allies, astonished at having conquered us, had halted at the sight of our territory, which they so long regarded as sacred. France, on her part, from the long habit of conquering, seemed to have retained a remnant of confidence which supported her amidst her adverse fortune. It was requisite to preserve these protective illusions. When the enemy should attack it would be time to retrograde. Our army, therefore, received orders to maintain its station along the Rhine. The enemy would respect this barrier long enough to justify our boldness in trusting to it; and the French Eagles floating on the left bank would lend support to the negotiations that were about to be renewed.

CHAPTER II.PROPOSITIONS MADE AT FRANKFORT. (November continued.)

Overtures for peace had just been made. At the opening of the British Parliament, on the 4th of November, the Prince Regent of England said: No disposition to require from France, sacrifices inconsistent with her honour, or just pretensions as a nation, will ever be on my part, or on that of his Majestys Allies, an obstacle to Peace.

On the 14th of November, Baron de Saint-Aignan arrived in Paris, charged by the Allied Powers, to make communications confirming these pacific intentions. M. de Saint-Aignan, who was the Emperors equerry, had recently been minister from France, to the Court of Weimar. A band of partizans had removed him from his residence; but his personal reputation, his connection with the Duke of Vicenza, and the interest with which he was regarded at the court of Weimar, contributed to his deliverance. M. de Metternich took advantage of his return to France, in order to communicate certain propositions to Napoleon. He invited M. de Saint-Aignan to Frankfort, and on the 9th of November, in a confidential conversation, at which were present, M. Nesselrode, the Russian minister, and Lord Aberdeen, the English minister, M. de Metternich laid down the bases of a general pacification, which M. de Saint-Aignan noted down from his dictation. These were the bases which M. de Saint-Aignan now presented to Napoleon.

The Allies offered peace on condition that France should abandon Germany, Spain, Holland, and Italy, and retire within her natural boundaries of the Alps, the Pyrenees, and the Rhine.

These conditions seemed very unreasonable, after those which had been proposed at Prague four months before. To abandon Germany, was only to submit to what the late events of the war had nearly decided; to abandon Spain, was merely to convert into a formal obligation, the inclination which was already felt to yield voluntarily to the resistance of the Spaniards: but to renounce Holland, which was wholly in our possession, and which afforded so many resources; to abdicate the sovereignty of Italy, which was entirely our own, and which presented forces sufficient to make a diversion to Austria,these immense sacrifices, Napoleon could only have been induced to make in return for a speedy and sincere peace, calculated to protect France against foreign invasion. But it was not the cessation of hostilities, but merely the opening of a negotiation, that was offered as the price of Napoleons adherence to the proposed bases. This point is important, and deserves to be attentively borne in mind. Accordingly, the last article dictated to M. de Saint-Aignan, set forth that if these bases were accepted, it was proposed to open the negotiation in one of the towns on the banks of the Rhine; but that the negotiation was not to suspend the military operations.

Next page