PRAISE FOR LYNDA SCHUSTERS A BURNING HUNGER:

This must rank as one of the most important contributions to the history of the period. It is simply required reading. The Northern Echo

A Burning Hunger is the history of a South African family that suffered, resisted and finally triumphed over apartheid: a book that is as fascinating as the best novels. Mario Vargas Llosa

It is strange that no South African writer has thought of doing what Lynda Schuster, an American journalist, has done so well in this bookfollow through the history of a black family in the context of the anti-apartheid struggle. The Sunday Times

This is an earnest and passionate historical account, crafted from meticulous research and study. It is a narrative made for captivating reading and painful reminder of the brutality of the apartheid system. The book is a welcome addition to a much needed but historically neglected genre of struggle biography. Reverend Frank Chikane, Director-General in the Office of South African President Thabo Mbeki

In A Burning Hunger, Lynda Schuster tells a tale that should have been told a long time ago. The Citizen

Although A Burning Hunger gives a clear insight into the politics of the time, it is the exposed humanity of the family members that makes this book so compelling and poignant. Brainstorm

The apostles of apartheid wanted African children to become hewers of wood and drawers of water. Lynda Schuster shows why those of Nomkhitha and Joseph Mashinini became brave freedom fighters instead. They were sustained by the spirit of their ancestors, their religious belief and their confidence in the leaders of the struggle. The story of the Mashininis is a lesson which both oppressors and democrats should read. George Bizos, human rights advocate and author of No One to Blame: In Pursuit of Justice in South Africa

It is a major contribution to the history of the struggle era, giving a human face to a family that was idolized by black South Africans and demonized in white South Africa. Business Day

The characters lives are filled with twists that make this book part Greek tragedy, part love story, and part thriller. Femina

A BURNING HUNGER

A BURNING HUNGER

One Familys Struggle Against Apartheid

LYNDA SCHUSTER

Ohio University Press

Athens

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

www.ohio.edu/oupress

Copyright Lynda Schuster 2004

First published in Great Britain in 2004 by

Jonathan Cape

Random House

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road

London SW1V 2SA

First published in the United States of America in 2006 by

Ohio University Press

The Ridges

Athens, Ohio 45701

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schuster, Lynda.

A burning hunger : one family's struggle against apartheid / Lynda Schuster. 1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: London : Jonathan Cape, 2004.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8214-1651-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8214-1651-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8214-1652-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8214-1652-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Mashinini family. 2. ApartheidSouth Africa. 3. Anti-apartheid movementsSouth Africa. 4. South AfricaRace relationsHistory20th century. 5. Civil rights workersSouth AfricaBiography. 6. Civil rights workers, BlackSouth AfricaBiography. 7. Political activistsSouth AfricaBiography. I. Title.

DT1757.M385 2006

323.092'268dc22

2005033771

for Dennis because of all his patience

Contents

Illustrations

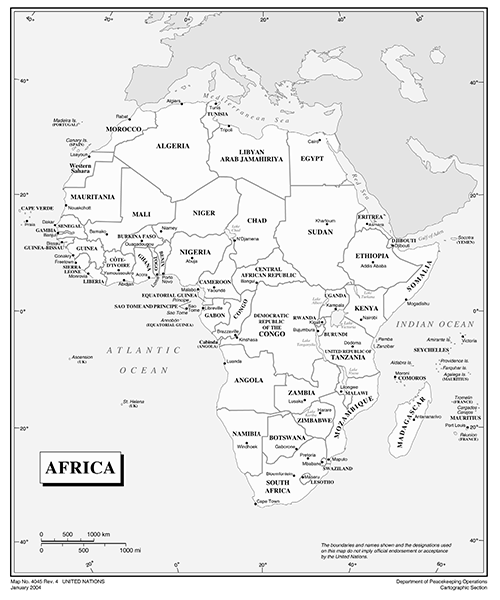

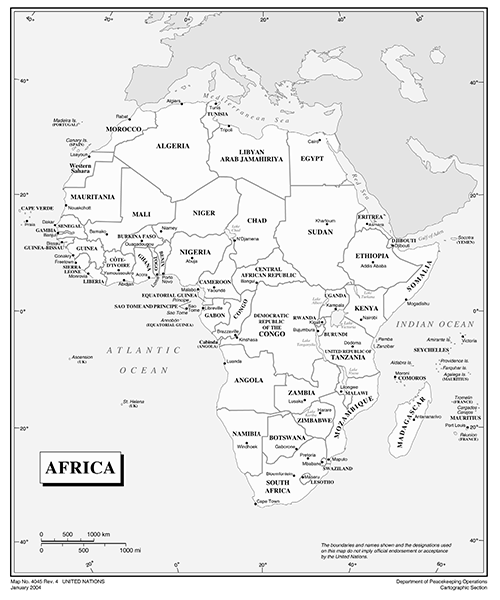

Map by World Sites Atlas (sitesatlas.com)

Prologue

On 4 August 1990, Tsietsi Mashinini finally came home.

Few were accorded the welcome given the young man. And rightly so: despite all his years in exile, Tsietsi remained a legend among South Africas black youth. He led the 1976 Soweto uprising, in which thousands of students rebelled against the white-minority government and hundreds died. Tsietsis ability to elude the police, as one of South Africas most wanted men, had made him a legend. He was spotted dressed as a stylish girl here, a workman there, a priest on the other side of Soweto, the vast black township. Then, just when the police seemed on the verge of capturing him, Tsietsi escaped over the border.

And so on that brilliant winter morning, hundreds of his admirers descended on Jan Smuts International Airport to await Tsietsis return. They jammed the cavernous arrival hall: chanting his name; singing liberation songs; doing the toyi-toyi, the war dance imported from Zimbabwean guerrilla camps that made them look as though they were running in place. Suddenly, a shout went up. Through the doors that led to the cargo area, the youths saw the pallbearers emerge, carrying the coffin. They saw the hearse pull up to the curb outside to receive it. They saw the family huddle around the vehicle, weeping. And they knew that Tsietsi Mashinini had finally come home.

This was not the way it was supposed to have happened. Like so many Africans, Nomkhitha, his mother, believed in the voices of the ancestors. Her long-dead father had appeared to her in a dream to say Tsietsi would return one day to rule South Africa; Nomkhitha had clung to that promise during all the years of her sons exile. But then came the telephone call telling of Tsietsis sudden and inexplicable death in an obscure West African country. So instead of a triumphal return by a conquering hero, a funeral procession of family and followers bore Tsietsi back to the city of his birth.

It was the end of a story that had, in one way or another, entangled all the Mashininis. For Tsietsi set in motion a series of events that would forever define his family. From the time of the Soweto uprising, the Mashinini name became a magical thing among black South Africans and a thing of infamy among whites. Many of Tsietsis twelve siblings and even his parents, heretofore mostly apolitical observers of the countrys gross inequities, were inexorably drawn into the fight against apartheid.

His oldest brother rose through the ranks of the outlawed African National Congress army to command freedom fighters, guerrillas who infiltrated South Africa from neighbouring countries and blew up military installations. Another was twice arrested for his political activities, brutally tortured, tried for treason, released only to go on to help orchestrate the insurrection that rocked the nation from 198486 and ultimately brought the white government to its knees. Yet another fled the country when he was only fifteen, was educated by the ANC in Egypt and Tanzania, and became a senior official in the ANCs exiled diplomatic service. Even Nomkhitha, the family matriarch, spent 197 days in solitary confinement in a South African prison.

Yet these are not members of a political elite. Like so many black South Africans, the Mashininis were ordinary people caught in extraordinary circumstances. Their tale is that of perhaps every other family in the townships: impoverished, law-abiding citizens who got sucked into the anti-apartheid struggle by the involvement of a child or sibling and whose lives changed irrevocably as a result. They became the foot soldiers in the fight for liberation. Mostly unnoticed and often with little publicity, these families made huge sacrifices that, in the end, proved essential in bringing down the white-minority government.