ALSO BY NORMAN LEBRECHT

NONFICTION

Who Killed Classical Music?: Maestros, Managers, and Corporate Politics

Mahler Remembered

The Maestro Myth: Great Conductors in Pursuit of Power

The Life and Death of Classical Music:

Featuring the 100 Best and 20 Worst Recordings Ever Made

Covent Garden: The Untold Story

The Companion to 20th-Century Music

The Book of Musical Anecdotes

FICTION

The Game of Opposites

The Song of Names

Copyright 2010 by Norman Lebrecht

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lebrecht, Norman, [date]

Why Mahler : how one man and ten symphonies changed our world / Norman Lebrecht.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37950-4

1. Mahler, Gustav, 18601911. 2. ComposersAustriaBiography. I. Title.

ML410.M23L44 2010

780.92dc22 2010006034

www.pantheonbooks.com

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

DESPERATELY SEEKING MAHLER

M y search for Gustav Mahler began in 1974 in a London edifice where a Beatle once got married and paparazzi hung out each morning in hope of another payday. Marylebone Town Hall and its adjoining public library embodied Victorian values of public order and enlightenment. The library stocked books in all disciplines, from trivial romances to nuclear science, and readers were encouraged to recommend new titles. I lived nearby in a dank basement flat, working unsocial hours in television news. Whatever leisure I had was spent reading and practicing the piano. My musical tastes were turning away from the confrontational sounds of my own generation to the challenging complexities of classical music. Sitting on backless choir benches at concerts in the Royal Festival Hall, I trained my eyes on conductors of many kinds in an effort to discover how gesture shaped sound. Subtler than rock, whose rhythm and dynamics contained little variation, orchestral music opened a door to a world of feeling and ideasif only I could fathom how it worked.

The concert notes I read were not much use to a struggling autodidact, rattling on as they did about subtonics and dominants, and newspaper reviews worshipped each morning at a shrine of Great Composers whose sanctity was taken for granted. As a child of my time I rejected established hierarchies. To find music that mattered to me, I attacked the music section at Marylebone library from top shelf to bottom, Alkan to Zelter, in pursuit of human affinities, relishing Charles Burneys birds-eye view of the 1784 Handel Commemoration, Stendhals life of Rossini, and the wonderfully acrid diaries of Hector Berlioz. William Reeds Elgar As I Knew Him, Marguerite Long on Ravel, and Agatha Fassetts observations of Bartk in exile added a flesh-and-blood dimension to the poignancy of their subjects music.

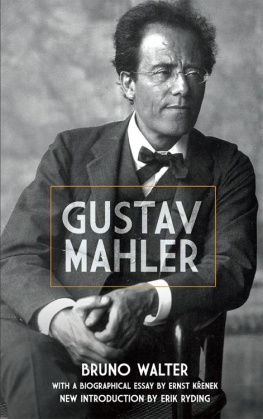

My reading was advancing at a rate of six loans a week when two books stopped me in my tracks. Alma Mahlers memoir of her marriage to a composer was so vivid, so incisive, so intrusively possessive, that I was consumed by a need to understand a man who could inspire such passionate ambivalence. It was published in 1940, when Mahler was widely banned, and there was a desperation to Almas tone, as if she feared that his life and hers had been wasted. Mahlers voice, crisp and assured, rang out in his letters. I ran back to the shelves, but there was nothing more to read until, weeks later, there arrived from the publisher Victor Gollancz the 980-page first installment of a projected biography by a French baron, Henry-Louis de La Grange, who seemed to know what Mahler was doing practically every waking minute. The mountain of intimate detail in this first volume (of four) drew yelps of astonishment from me, reading on shift at the BBCs Newsnight show, and prompting the newscaster to ask if war had broken out.

What struck me in these accounts of Mahlers life was my familiarity with his experience. There was not much I could relate to in the lives of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven: Their loves were unfathomable, their routines dull, their diseases medieval, and their fortunes dependent on patronage. Mahler was a self-made man, driven by ambition. He dealt with issues I could recognize: with racism, workplace chaos, social conflict, relationship breakdown, alienation, depression, and the limitations of medical knowledge. My time will come! he vowed, confident that his works would someday find a sympathetic audience. I also took this to mean that he was living outside his time frame, fast-forwarding to a future date. It struck me that the best way to approach Mahler was to treat him in the present continuous, as a man of my own time.

My search for Mahler would, I realized, need to cover every footstep of his odyssey from a land without a name to world fame in Vienna and New York, as well as every aspect of his personal conduct, from the way he made love to how he knotted his tie. (Arnold Schoenberg once said you could learn more about music from watching Mahler get dressed than from any conservatory lecture.) I first went to Vienna in 1983 to write a feature for the Sunday Times and, after a rehearsal of Mahlers Second Symphony in the Musikvereinsaal, walked twice around the Ring on a subzero winter night. I talked my way into Mahlers apartment (where his bathtub was still in use), stroked Rodins cast of his head in the Opera foyer, and placed a pebble on his grave in Grinzing. Broad-minded travel editors helped me to visit Mahlers birthplace, the small towns where he made his career, and the summerhouses where he composed. Reeling with vertigo, I scaled a mountain peak that inspired the Third Symphony. In Helsinki I relived the crossroads encounter between Mahler and Sibelius. In the Czech Philharmonic archive in Prague, I studied symphonic scores with Mahlers red-and-blue pencil marks. In the pin-quiet reading room of the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, I looked at side-by-side manuscripts of his Second, Fifth, and Ninth Symphonies, charting the changes in his handwriting.

Along the route I found relics. A grungy bookshop in Amsterdam yielded a copy of stage designer Alfred Rollers scarce iconography. A riffle through a Munich railway terminus store produced an uncatalogued photograph of Mahler on the podium. A chat at a cocktail party disclosed unpublished letters. By 1987 I had acquired so much Mahleriana that, needing to clear the desk, I wrote Mahler Remembered, a portrait of Mahler through the eyes of those around him. The month that book came out I moved into a flat in St. Johns Wood, London, where, it turned out, the old lady on the top floor had attended Mahlers wedding and had the invitation to prove it. Mahler, it seemed, was following me to my lair as much as I was pursuing him.

Down the years the book I wanted to write changed from musical biographythere were several in existence by nowto one that would try to address the riddle of why Mahler had risen from near-oblivion, to displace Beethoven as the most popular and influential symphonist of our age:

Why Mahler? Why does his music affect us in the way it does? Are we hearing what he meant us to hear, or a figment of interpretation? Why does Mahler make us cry?