Introduction

Thinking Outside

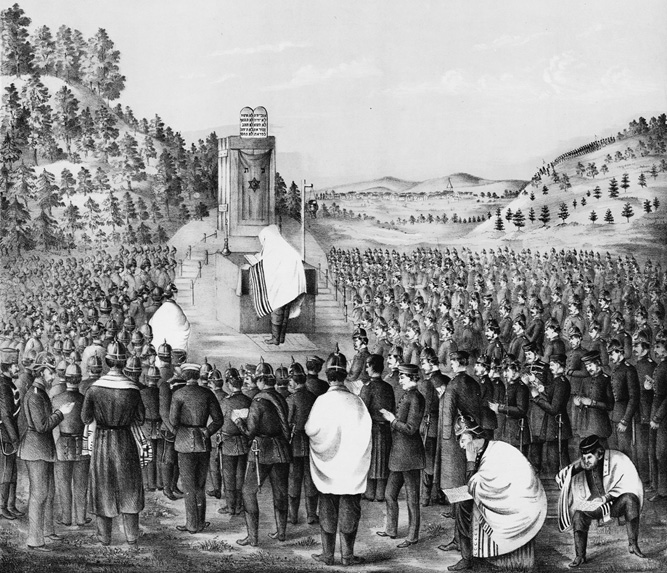

Between the middle of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a handful of men and women changed the way we see the world. Some of their names are on our lips for all time: Marx, Freud, Proust, Einstein, Kafka. Others have vanished from our collective memory but their importance endures in our daily lives. Without Karl Landsteiner, for instance, there would be no blood transfusions or major surgery, without Paul Ehrlich no chemotherapy, without Siegfried Marcus no motor car, without Rosalind Franklin no model of DNA, without Fritz Haber not enough food to sustain life on earth, without Genevive Halvy no Carmen , without Emanuel Deutsch no state of Israel.

What these transformers have in common is being Jewish, some by having Jewish parents, others by practising the Jewish faith. All appear to think outside the box and all of them think fast. Why, at this period, a handful of Jews managed to see what others could not is the subject of this book.

There is a reverse side to the proposition. If Jews remade the world between 1847 and 1947, did the world also change Jews, perhaps beyond recognition? (Short answer: yes.) No historian has, to my knowledge, addressed the story from both aspects. In a multicultural twenty-first century, there may be a wider relevance to these engagements as a template for cultural dialogue and symbiosis.

Folk wisdom has it that five Jews wrote the rules of society:

Moses said the Law is everything

Jesus said Love is everything

Marx said Money is everything

Freud said Sex is everything

Einstein said Everything is Relative.

Ha-ha, but more than half-true. And Jews have a half-truism for most things. A century before Christ, a man demanded to be taught the whole of the Torah while standing on one foot. Hillel the Elder said: Love your neighbour as yourself. The rest is commentary. Two millennia later Albert Einstein, asked by a journalist to explain the theory of relativity, replies: Matter tells space how to curve. A Hillelian aphorism. When the hack still looks blank, Einstein tells a Jewish joke. That works (see page 203).

The Jewish mindset behind the wave of genius has not been successfully explored. How much do Jewish elements in their background inform Mahler, Modigliani, Proust? How does Freud know that sex is the source of most unhappiness? What makes Marx hate Jews? How much do science and mass migration affect rabbinic thinking, not to mention the physical shape of Jews? When is being Jewish a virtue? Why cant the world see what, to one or two Jews, is blindingly obvious?

The tendency to take a different point of view is illustrated by an anecdote apocryphal of the head of a famous Lithuanian yeshiva (rabbinic college) who chides his students for playing football in their lunch break when they could be discussing pearls of Torah. But football is a beautiful game, kevod harav [honoured rabbi], they protest. Let us show you. At the next weekday league match in Vilna, featuring the nations best players, the students and their rav take seats in the stands. At half-time, the young men ask the rav for his response.

I have solved your problem, he replies.

How, kevod hara v ?

Give one ball to each side and they will have nothing to fight over.

The rosh yeshiv a s way of thinking is counter-intuitive to the western method, which starts with observing the facts on the ground twenty-two men and a football before seeking to understand them in a context of social interaction. The ra v , unaware of the rules, sees the game from a fourth dimension, a world apart from the situation. He offers a solution which, while irrelevant to the game of football, has a certain angelic elegance and ethical rightness.

Aspects of the ra v s solution can be sighted in Benjamin Disraelis deconstructive approach to British politics, in Sarah Bernhardts exploitation of fame and, critical for the outcome of the Second World War, in Leo Szilrds cracking of the atom: he saw a way to the future the shape of things to come. Time and space are flexible for Szilrd, as they are for Einstein, Haber, Meitner and Kafka, because their grasp of time and space is not confined to white lines on green grass. Jews speak of Jewish time as a relative measurement; the Talmud establishes a relative hour, also known as an halachic hour, which varies in length from one day to the next according to the Suns position. Relative time is part of Einsteins genetic heritage long before he announces the discovery of relativity.

Sigmund Freud declares on several occasions that he was brought up in an irreligious home and that he knows nothing about Judaism. It will come as a shock to any researcher with a knowledge of the Talmud to find that Freud uses no fewer than six of the thirteen rules of Talmudic exegesis unconsciously, no doubt in his analytic approach. It is no less eye-opening to find Marx exposing a profound familiarity with Jewish toilet manners or Trotsky being so sensitive to left-wing anti-Semitism that he denounces it in Pravda as early as 1923. Prousts madeleine is almost certainly baked with a Jewish recipe. Kafka dreams of waiting on tables in a Tel Aviv caf. Their Jewish psyche neither sleeps nor slumbers.

There is another connective factor. In every person of genius who appears in this book there runs a current of existential angst. Jews in the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth are gripped by a dread that their rights to citizenship and free speech will be revoked. After the Dreyfus Trial, great minds are driven by a need to justify their existence in a hostile environment and to do it quickly, before the next pogrom. They do not expect acceptance. On the contrary, knowing that their ideas are likely to be rejected leaves them free to think the unthinkable, and forced to do so at speed, before the next crisis. It is no coincidence that Freud, Einstein, Schoenberg, Proust, Herzl, Trotsky, Haber and Hirschfeld all rise in the decade after Dreyfus, a turning point whose magnitude is generally unacknowledged outside France. Dreyfus reawakens a primal fear in his fellow Jews, a token of their marginality and therefore of their opportunity.

For Kafka, alienation is not a Jewish problem, nor even a personal shortcoming; he extrapolates it as an essential symptom of the universal human condition. Gershwin, the first American-born songwriter to earn international acclaim, is only happy at parties when he is sitting at a piano in the corner of the room, figuring out the meaning of it all. Schoenberg, asked if he is the man who makes that horrible, atonal music, says: Well, someone had to, so it might as well be me. A Jew, steeped in concerns for collective survival, is free to go where angels fear to tread, thinking well, whats the worst thing they can do to me? Angst, a sense of dread or apprehension (from the Latin anxiu s ), is regarded by most psychologists as a negative, inhibiting emotion. Freud does not see it that way. Among Jews, anxiety is a primary motivating factor, the engine of fresh thinking.