This book tells, for the first time, the true story of Mohammed Mansour Jabarah, a young Canadian who was recruited into terrorism, and the international intelligence operation that brought him down. It is about the radicalization of one man, but at the same time it is the story of the thousands of other youths who are being lured into terrorist groups in much the same way. When I embarked on this project, I felt that by looking closely at how a seemingly ordinary high school graduate from Canada was transformed into a trained killer for his God, I could understand what was motivating so many others, especially in North America and Europe, to fall under the spell of Osama bin Laden, Abu Mussab Al Zarqawi and their murderous peers.

Because Jabarah traveled so much during his brief but stellar Al Qaeda career, I thought it was important to follow in his footsteps to experience the world he passed through on his way to becoming a full-fledged terrorist. I retraced his journeys across three continents, from Canada to the Middle East to Southeast Asia, and drew upon my reporters notebooks from assignments in Pakistan in 2004 and Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002. The book is therefore not only about Mohammed Jabarah and his fellow recruits, but also the people, places and ideas that shape their dangerous outlook on the world.

Much has already been written in the press about Jabarah. Some of it was accurate. Some of it was not. In all of these journalistic fragments, however, Mohammed was never more than a disembodied name. I wanted to know who he was and why he did what he did. This was not an easy task. It is challenging to write a book about someone you have never met, especially a terrorist about whom little information has ever been officially released. This was the hardest story I have investigated in more than 15 years as a journalist. I wrote letters to Mohammed in prison, asking him to tell me his story, but I never received a reply. Likewise, phone calls and a letter to his lawyers went unanswered. I also sent many requests to the Canadian government asking for the disclosure of documents about Jabarah under the Access to Information Act. With a few minor exceptions, all were denied for reasons of national security and personal privacy.

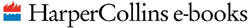

Although I was never able to interview Jabarah, when I followed him around the world I did find his trail. I was also able to find out what Mohammed had told the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and FBI investigators, who documented what he said in various intelligence reports. I interviewed people involved in the Jabarah investigation and studied the statements that those who worked most closely with himKhalid Sheikh Mohammad and Hambalihave given to interrogators since their capture. Finally, I spoke at length with the Jabarah family, who shared with me some of Mohammeds personal effects: report cards, family photos and letters from prison. While some may question the veracity of interrogation reports, especially following the recent concerns about the treatment of U.S. detainees, the version of events reported by the FBI is identical to the one documented independently by CSIS, and both accounts are consistent with the other available information on Jabarah. Since intelligence leaks are a politically charged topic for some, I note that none of the CSIS or FBI documents I obtained were leaked to me by either CSIS or the FBI. They were either released under the Access to Information Act or obtained from trusted third parties who had access to them.

In addition to finding out how Mohammed was recruited, I also wanted to know how he was brought to justice, which, it turns out, is one of the most misunderstood parts of the Jabarah case. The story told here is unusualit is an account of a successful intelligence operation. This is not to say that such successes are rare, but that they are rarely told. One of the realities for intelligence agencies is that their successes are hardly ever known, while their failures become common knowledge. This helps feed a commonly held public perception that those who work in the field of security and counterterrorism are incompetent. My experience, both in Canada and abroad, is that this is far from the truth.

The book can be divided roughly into three sections. The first, chapters 1 to 5, tells the story of Mohammeds childhood in Kuwait and Canada, and Al Qaedas early efforts to recruit him. The second section, chapters 6 to 12, chronicles his Al Qaeda training and operational assignments. The final section, chapters 13 to 18, deals with the aftermath of Mohammeds capture.

Jabarah was not the most important person in Al Qaeda, but that is partly why his story is so compelling. High-ranking leadership figures like bin Laden are no longer the only worrisome part of the international jihadist movement. Equally frightening are the mostly young men like Mohammed, who are volunteering to fight and die for the global jihad. People like bin Laden and Al Zarqawi are nothing without their dedicated foot soldiers. While counter-terrorism agents are rightly pursuing the leaders, Jabarahs story shows us that they must also ensure they are paying close attention to the significant pool of recruits. If terrorism is to be stopped, the incitement, indoctrination and recruitment of the Mohammed Jabarahs of the world must be disrupted.

The names, dates, places and events in this book are real, and I have presented them as accurately as possible. Some of the written source material I relied on was translated from Arabic, as were many of the interviews. Dollar figures are in U.S. currency unless otherwise stated. Finally, any references to the religious, ethnic, national or other attributes of terrorists are obviously not meant to suggest that all members of these groups are terrorists.

I want to thank Don Loney, my editor at John Wiley & Sons in Toronto, who encouraged me to write this book and skillfully saw it through all stages of development. Thanks also to Robert Harris, Meghan Brousseau and the rest of the team at Wiley Canada, as well as Pat Cairns at Creative Connections. The photojournalist Jeff Stephen of Global National accompanied me on most of the journeys described in the book and I appreciate his contributions, energy and companionship. Thanks also to George Browne and Kevin Newman. I would like to thank all those who saw the value of telling the Jabarah story properly and completely, especially those who shared with me the pieces of the puzzle in their possession and trusted that I would put them together responsibly.

The travels described in the book would not have been possible without the assistance of the diplomats, soldiers, civil servants, journalists, fixers, drivers and others who guided me when I was abroad, particularly Stewart Innes in Kuwait City, Rahimullah Yusufzai in Peshawar and Rohan Gunaratna in Singapore. I appreciate the cooperation of Mansour Jabarah, who was, if nothing else, a gracious host. Many thanks to Rita Katz and her staff at the SITE Institute, who found and translated some of the documents. Thanks also to Michael Elsner at Motley-Rice and the United States Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton for sharing their documents. Maha Talkah translated some of the Arabic documents and provided valuable insights into their meaning and context.