Originally published in 1991 by Prentice Hall Press

Published 2001 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2001 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 00-55985

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gold, Herbert, 1924

Haiti : best nightmare on Earth / Herbert Gold ; with a new

afterword by the author.

p. cm.

Originally published in 1991 by Prentice Hall Press, under the

title Best nightmare on Earth : a life in Haiti.

ISBN: 0-7658-0733-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. HaitiDescription and travel. 2. HaitiSocial conditions.

I. Gold, Herbert, 1924-Best nightmare on Earth. II. Title.

F1917 .G65 2000

972.9407dc21

00-55985

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0733-5 (pbk)

With grateful friendship to Jean Weiner,

Jacques Large, Al Seitz, F. Morisseau

Leroy, Shimon Tal, Shelagh Burns, Issa el

Saieh, and to some who cannot be named.

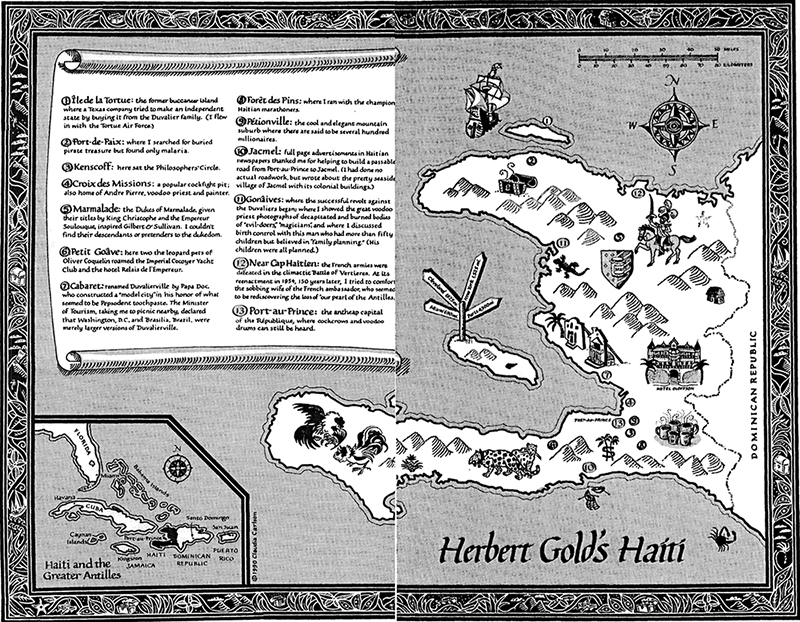

This is an account of my times in Haiti, from the years of the early fifties when I lived there as a young student to my most recent visit in 1990 as a less-young traveler. I have changed some names and identifying details. As in the past, some of my Haitian friends will not be happy with my reporting; but they know I keep coming back because their country is still the magic island.

Haiti was the first independent black nation of modern times, winning its freedom from France with a slave revolt against Napoleon at the height of his power. Here is the first sentence of a primary school reader still in use in the 1950s:

Nos anctres, les Gaulois, avaient les yeux bleus et les cheveux blonds.

Our ancestors, the Gauls, had blue eyes and blond hair.

We are very much interested in Haiti, said the American Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, in 1913, to the Ambassador from Haiti. Tell me about the country and who the people are. Where is Haiti?

.

Dear me, think of it! Niggers speaking French.

CHAPTER

ONE

1953: The Golden Age of Strange

N PARIS I met the teasing, laughing, flirting, Haitian bride of a black American friend. The lady, a singer and dancer, was the daughter of a poor family which lived in a cinder-block house a short walk from the National Palace in Port-au-Prince. Haiti has a National Palace? I asked.

It doesnt have a tin roof, she said. My mothers house does. And then the inexorable winding down of my G.I. Bill and Fulbright sinecures brought me back to my hometown, Cleveland, the Paris of northeastern Ohio, to await the fame and riches which would surely fall from the heavens (New York) after publication of my first novel. The novel came out; I hurried to the Post Office in the Public Square; my picture failed to appear on the new three-cent stamp.

I had a wife, two babies, no good prospects to support them. I remembered the laughing Haitian singer and dancer. I went to the library to look up scholarships and fellowships and applied for one to take me to the Universit dHaiti. In due course, I was on a ship traveling from New York to Panama, with a stop in Port-au-Prince.

Steaming south along the coast on a white Panama Lines vessel, I watched a tall, imperious Haitian, with an aquiline nose, impeccably dressed, pacing the deck. I admired his self-possession, and as a very young man enraptured by everything different from Cleveland, Ohio, I wondered about his manner of proud exasperation. A quality I had not developed and could only admire from afar was the talent for being elegantly pissed-off.

In the way of travelers, eventually we spoke, and we became friends for the next quarter of a century. As the years went by, his exasperation grew. Haiti gave him plenty to be exasperated about, although he would not leave his country except for brief visits.

This tall black man pacing the deck, Jean Weiner, was an electrical engineer. His family, from the town of Jacmel, had been in the coffee-exporting business. A certain molding of his face and the prominent nose carried on the look of one of his grandfathers, a Jew fromas his name suggestedVienna. Later I met other good Roman Catholic or voodoo-believing Haitians with ancestors among the wandering Jews who at times had pressing reasons to make their lives in this hidden and unlikely place. Educated in Paris and the United States, an angry and generous soul, Jean was my first friend among the class of Haitians called the eliteAfrican and French and Haitian all at once, and negotiating their lives and their history with unique charm and difficulty.

When the coastal waters began to turn tropical, Jean changed into a white linen suit and began to groan about the island where I was coming to spend the next yearthe next year and, as it turned out, a part of every next day and night of my life. Ah, Herb, go back, go home while you can! he said, and I laughed, treating this as a joke.

In fact, Haiti was not bad to me. Haiti was mostly bad to Haitians.

The white Panama Lines ship passed the lie de la Gonve, where uncounted people lived without electricity, machinery, or contact with the larger world of Port-au-Prince and the mainland. I had tried to prepare myself by reading everything I could find in English and French and so I said, Oh yes, the White King of La Gonve, remembering one of the romance-drenched books. These accounts were normally illustrated with woodcuts of drum-beaters or voodoo ceremonies, all staring eyes and licking flames.

You think youre ready, Jean Weiner said. My dear friend, you are not ready.

The bay of Port-au-Prince was like a black mirror reflecting the heat. Frantic boys in burned-out log canoes were begging for coins alongside the ship, diving into the murk and coming up gasping for more, another, vite, moin, vite! Jean extended his long arm to offer me the entire city, spread out in a yellow-gray haze along the wide, wide baya low jumble of thick-walled colonial buildings and corrugated tin sheds nearby, and the smoking slum of La Saline, then the irregular slopes with spots of gardens, cloud-shrouded mountains rising into the distance above the town.

I landed with household goods for four; my family would follow by airplane when I found a house. The tropical rush, noise, heat, and harborside dust gave me a dizziness of expectation. I braced myself to sink into clamor as a team of port officials, sweating primly and stubbornly in clothes made for another climate, asked for my papers. Passport, please! The startled customs chief looked up, smiling, and waved me through with a welcoming largeness. He was, he declared, an immense and devoted Haitian

N PARIS I met the teasing, laughing, flirting, Haitian bride of a black American friend. The lady, a singer and dancer, was the daughter of a poor family which lived in a cinder-block house a short walk from the National Palace in Port-au-Prince. Haiti has a National Palace? I asked.

N PARIS I met the teasing, laughing, flirting, Haitian bride of a black American friend. The lady, a singer and dancer, was the daughter of a poor family which lived in a cinder-block house a short walk from the National Palace in Port-au-Prince. Haiti has a National Palace? I asked.