Dubois - Haiti: the aftershocks of history

Here you can read online Dubois - Haiti: the aftershocks of history full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York;Haiti, year: 2013, publisher: Henry Holt and Co.;Metropolitan Books, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Haiti: the aftershocks of history: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Haiti: the aftershocks of history" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Dubois: author's other books

Who wrote Haiti: the aftershocks of history? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Haiti: the aftershocks of history — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Haiti: the aftershocks of history" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For Georges Anglade, whose writings illuminated the past and present of Haiti,

and for all those who, like him, died in the earthquake of January 12, 2010

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

For eighty years Haiti has been judged, Louis-Joseph Janvier wrote in 1883. Since the birth of their country in 1804, Haitians had been incessantly accused by outsiders, and it was time for them to respond.

A Haitian student living in Paris, Janvier was particularly outraged by a set of newspaper articles by Victor Cochinat, a visitor from the French colony of Martinique. Having spent a scant few weeks in Haiti, Cochinat had penned a cutting portrait of the countrys culture, its people, and its politics. Some of his complaints were just those of a grouchy traveler: the porters in the harbor were disorderly and ill-clad, there was no set price for anything, Haitis capital city of Port-au-Prince was dirty and unpleasant and full of beggars. But Cochinat quickly extrapolated much more. Haitians were lazy and ashamed of work, he wrote, which was why they were so poor. They spent too much money on rum. The children of the country were lively and intelligent, but their parents gave them funny namesinstead of Paul or Jacques, they chose the names of Haitian heroes, Greek philosophers, and French writersand these, Cochinat asserted somewhat mysteriously, interfere with their intellectual development. He teased that Haitians, having freed themselves from slavery, seemed enamored of the whip, using it against their children. Haiti, as he saw it, was a farce, a phantasmagoria of civilization. It was a nation of admirals without boats, generals without soldiers, and schools without teachers: a hopeless and absurd place with no future. Its attempt to look like a modern country was nothing more than a joke.

Seething, Janvier wrote a sardonic six-hundred-page history of Haiti and its visitors. Many of these visitors had, like Cochinat, breezed through Haiti and then penned authoritative-sounding condemnations of the entire country. Janvier demanded at least a shred of objectivity. Was Haiti the only country with beggars in the streets? Hed noticed quite a few in Paris. Was it wrong for parents to name their children after great figures, in the hopes that their children would achieve great things? Janvier found himself having to remind his readers that Haitians were real people, living in a real society. They had their problems, to be sure, but they could not be reduced to mere caricatures, presented with no sense of context or history.

Janvier himself knew Haitis challenges intimately. When he was born in 1855, Haiti was dominated by the unpopular emperor Soulouque, and of the five presidents who had ruled by the time he wrote his book, four were violently overthrown, with the country torn apart by civil wars. Janvier served his nation as a diplomat, a judge, and a politician, trying to confront the forcesboth external and internalthat were holding the country back. He also became one of Haitis great intellectuals; his fourteen books included several novels, a critique of European racism, and the classic study of Haitis constitutional history. His defenses of his beloved land were eloquent, impassioned, erudite, and often funny.

But Janvier wasnt able to bring much change to Haiti; and he didnt make much of a dent, either, in the overwhelmingly hostile and distorted views held by most outsiders about the country. A few years after Janvier died, yet another Haitian president was overthrown in a bloody coup. The country was then occupied by the U.S. Marines, several of whom wrote popular accounts that portrayed Haiti as a dismal, backward place, full of lazy (if sometimes charming) peasants in the thrall of Vodou. In the decades since then, a succession of economic troubles and dictatorial regimes like that of Franois Papa Doc Duvalier have reinforced the negative stereotypes. When Haiti appears at all in the media, it registers largely as a place of disaster, poverty, and suffering, populated by desperate people trying to escape.

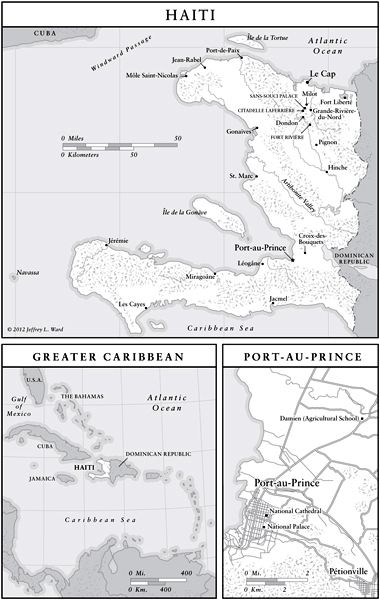

On January 12, 2010, Haiti was struck by one of the deadliest earthquakes in modern history, which killed upwards of 230,000 people and left millions homeless. The countrys National Palace, Port-au-Princes historic cathedral, and the headquarters of the U.N. mission in the country were demolished. As troops and relief workers rushed to help, the familiar tropes emerged again. Nearly every mention of Haiti in the press reminded readers that it was the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere, a moniker incessantly repeated like some dogged trademark. The coverage often made the country sound like some place entirely outside the Westa primitive and incomprehensible territoryrather than as a place whose history has been deeply intertwined with that of Europe and the United States for three centuries. And when people wanted to know how Haiti had come to be so poor, and why its government barely functioned, pundits offered a plethora of ill-informed speculation, like so many modern-day Cochinats. Many seemed all too ready to believe that the fault must lie with the Haitians themselves.

The day after the earthquake, televangelist Pat Robertson famously opined that Haitians were suffering because they had sold themselves to the devil. A more polite version of the same argument came from New York Times columnist David Brooks, who accused Haiti of having progress-resistant cultural influences, including the influence of the voodoo religion. Why else would the country be so poor, so miserable, when its immediate neighbor the Dominican Republicright there on the same island of Hispaniolawas a comparatively prosperous Caribbean tourist attraction? Many called openly for Haiti to be made a protectorate. Brooks advocated intrusive paternalism that would change the local culture by promoting No Excuses countercultures. Against such claims, other voices responded by placing the blame for the situation entirely on outside forces: foreign corporations, the U.S. and French governments, the International Monetary Fund. Nearly all of the coverage portrayed Haitians themselves as either simple villains or simple victims. More complex interpretations were few and far between.

But the true causes of Haitis poverty and instability are not mysterious, and they have nothing to do with any inherent shortcomings on the part of the Haitians themselves. Rather, Haitis present is the product of its history: of the nations founding by enslaved people who overthrew their masters and freed themselves; of the hostility that this revolution generated among the colonial powers surrounding the country; and of the intense struggle within Haiti itself to define that freedom and realize its promise.

* * *

A little more than two hundred years ago, the place that we now know as Haitithen the French colony of Saint-Dominguewas perhaps the most profitable bit of land in the world. It was full of thriving sugar plantations, with slaveswho made up nine-tenths of the colonys populationplanting and cutting cane and operating the mills and boiling houses that produced the sugar crystals coveted by European consumers. The plantation system was immensely lucrative, creating enormous fortunes in France. It was also brutally destructive. The plantations consumed the landscape: observers at the time already noted that alarmingly large areas of the forests had been chopped down for construction and for export of precious woods to Europe. And they consumed the lives of the colonys slaves at a murderous rate. Over the course of the colonys history, as many as a million slaves were brought from Africa to Saint-Domingue, but the work was so harsh that even with a constant stream of imports, the slave population constantly declined. Few children were born, and those that were often died young. By the late 1700s, the colony had about half a million slaves altogether. It was out of this brutal world that Haiti was born.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Haiti: the aftershocks of history»

Look at similar books to Haiti: the aftershocks of history. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Haiti: the aftershocks of history and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.