Who Owns Haiti?

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA

Florida A&M University, Tallahassee

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton

Florida Gulf Coast University, Ft. Myers

Florida International University, Miami

Florida State University, Tallahassee

New College of Florida, Sarasota

University of Central Florida, Orlando

University of Florida, Gainesville

University of North Florida, Jacksonville

University of South Florida, Tampa

University of West Florida, Pensacola

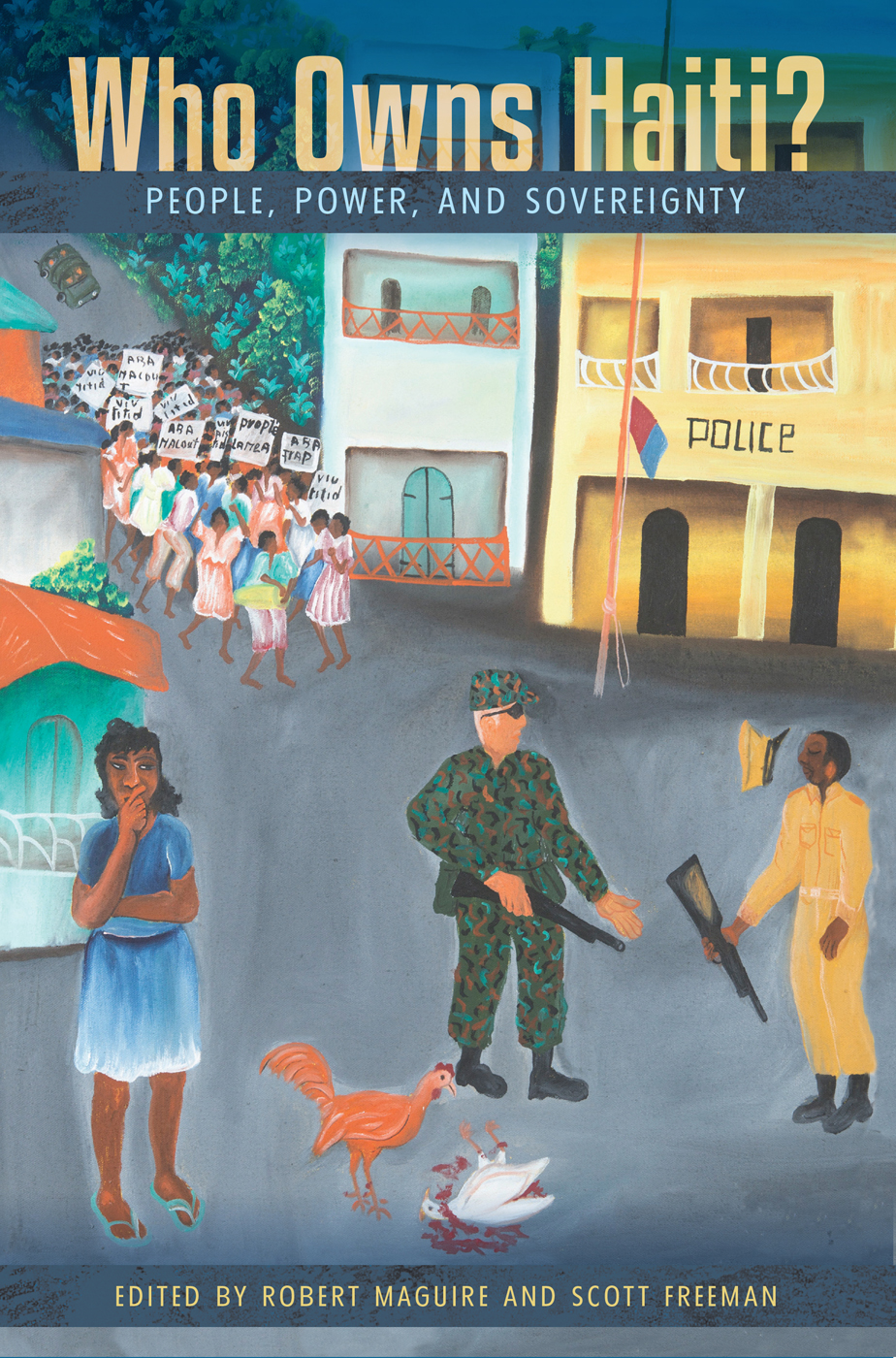

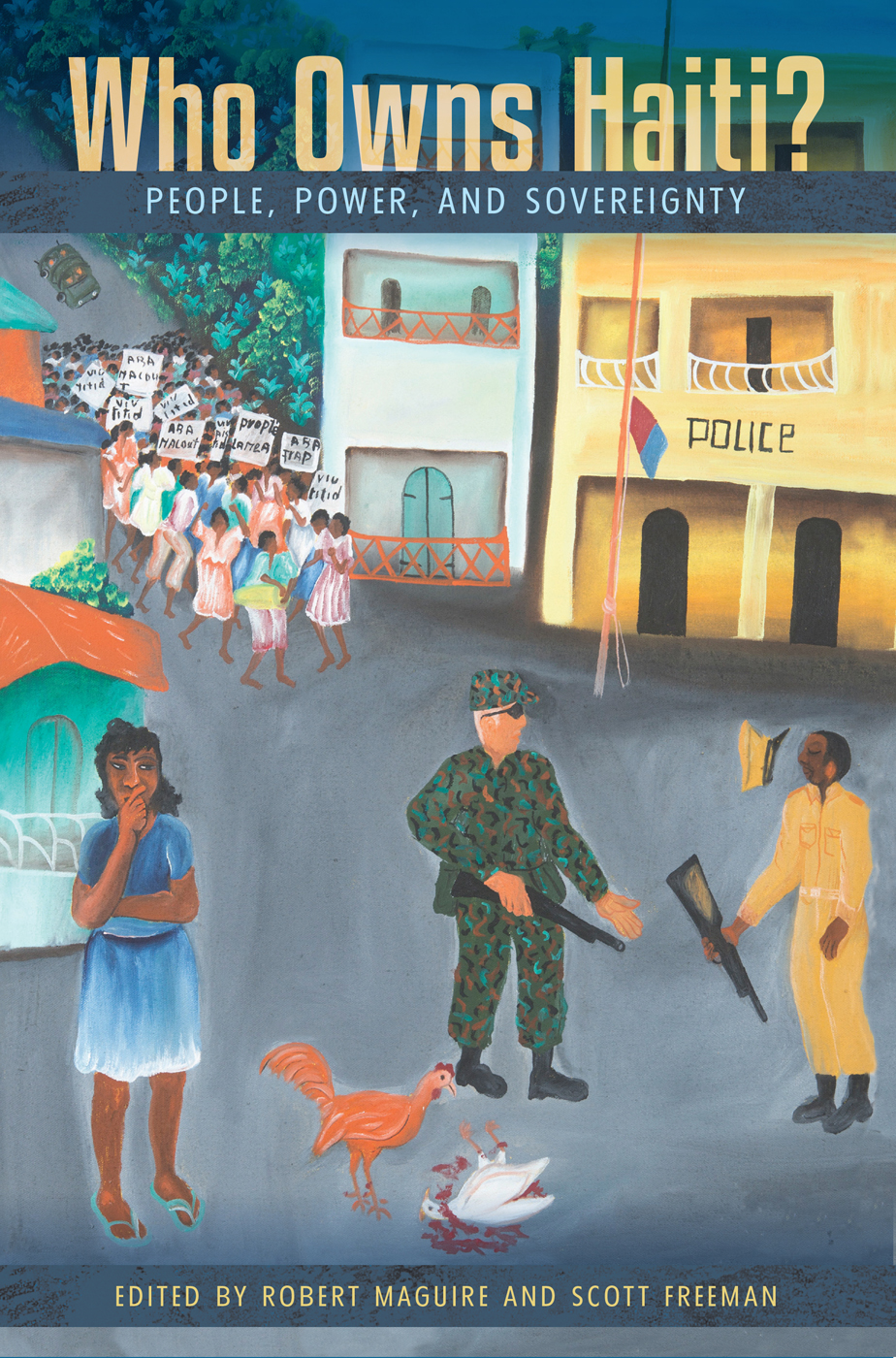

Who Owns Haiti?

PEOPLE, POWER, AND SOVEREIGNTY

Edited by Robert Maguire and Scott Freeman

Foreword by Amy Wilentz

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA

Gainesville / Tallahassee / Tampa / Boca Raton

Pensacola / Orlando / Miami / Jacksonville / Ft. Myers / Sarasota

Copyright 2017 by Robert Maguire and Scott Freeman

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

This book may be available in an electronic edition.

22 21 20 19 18 17 6 5 4 3 2 1

First cloth printing, 2017

First paperback printing, 2017

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Maguire, Robert E. (Robert Earl), 1948 editor. | Freeman, Scott (lecturer), editor.

Title: Who owns Haiti? : people, power, and sovereignty / edited by Robert Maguire and Scott Freeman ; foreword by Amy Wilentz.

Description: Gainesville : University Press of Florida, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016035948 | ISBN 9780813062266 (cloth) | ISBN 9780813064598 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: HaitiPolitics and government1986 | Self-determination, NationalHaiti. | HaitiHistory.

Classification: LCC F1928.2 .W47 2017 | DDC 972.94dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016035948

The University Press of Florida is the scholarly publishing agency for the State University System of Florida, comprising Florida A&M University, Florida Atlantic University, Florida Gulf Coast University, Florida International University, Florida State University, New College of Florida, University of Central Florida, University of Florida, University of North Florida, University of South Florida, and University of West Florida.

University Press of Florida

15 Northwest 15th Street

Gainesville, FL 32611-2079

http://upress.ufl.edu

Contents

Amy Wilentz

Scott Freeman and Robert Maguire

Laurent Dubois

Robert Fatton Jr.

Francois Pierre-Louis Jr.

Ricardo Seitenfus

Robert Maguire

Karen Richman

Scott Freeman

Chelsey Kivland

Robert Maguire, Scott Freeman, and Nicholas Johnson

Illustrations

Figures

Tables

Foreword

Amy Wilentz

Ever since I first began thinking about Haiti, the question this book addresses has been a focus of my investigations, no matter which book or story I was working on. Ownership is the core question at the heart of Haitian and, indeed, of all African American history. Of course the question of sovereignty is paramount for any entity that calls itself a state, but there is also an undercurrent in Haitian domestic politics and in foreign policy toward Haiti that is constantly posing the foundational question for the Haitian nation. That question is not just who owned and who owns Haiti, but who owns the Haitians themselves.

Who owns the government, who owns le terroir, who owns the people? Are Haitians the masters of their fates, either as citizens or as individuals? Who controls their destiny?

I arrived in Haiti for the first time at the end of January 1986 and witnessed the fall of the Duvalier dynasty that year. Since then, Ive watched a variety of regime changes there, many of them including elections, some not. During almost all these relinquishings and takings of power, the manipulations and counsel of the United States (and the other friends of Haiti, like France, Canada, the Vatican, and especially the UN) were an extremely important (if not the most important) factor. During each regime change, the United States worked to find the candidate most acceptable to business actors in Haiti and their friends and associates abroad. These candidates were usually moderates or conservatives, often English-speaking, who had international connections and were expected to stay an economic course that would help the export-import sector as well as maquiladora owners and large landholders.

The exceptions to this rule were the elections of Jean-Bertrand Aristide and (to a lesser degree) Ren Prval, who slipped around the American strategy on a huge wave of popular support. Aristides course through the sieve of U.S. policy for Haiti provided evidence of how far the Americans were willing to go to impede change in Haitis status quo. Removed once for his impolitic behavior toward the Haitian kleptocracy, Aristide was considered to have been detoxed by the time Bill Clinton reintroduced him into the Haitian political petri dish, but he was recidivist and had to be removed again.

Of course, Haitian history did not begin with the fall of the Duvaliers. It began with the Haitian Revolution, a historic battle between property and owner and between labor and capital. At its very inception, the worlds first black republic implied a battle over ownership, and Haitis revolution a claim to self-ownership.

Recently I had an experience in Haiti that surprised me even though it shouldnt have. In 2013, I was making my belated first visit to the Citadelle Laferrire, King Henri Christophes postrevolutionary testament to the former slaves fear that outsiders would reimpose slavery.

I was chatting with a man who was walking a donkey next to me; he was hoping I would tire on the steep uphill walk and need paid transportation. I asked him where he was from. He said Here. Well, I asked him, and where is your family from? Here also, he said. He said that as far back as anyone in his family had ever been able to remember, they were from here, and it came on me in a sudden wave of shock that of course he was, literally, the descendant of the people who built the Citadelle, and that all around me, walking up this steep mountainside to the fortress in the clouds, were descendants of those builders, dressed in ragged clothing today as those people had no doubt been, thin and strong, hardy survivors of history, still in place, descendants of revolution, true, but at the same time descendants of chattel. Perhaps the plantation their forefathers had worked as slaves once stood right here in the shadow of the lofty crest on which the Citadelle was built. Continuing my speculation, its entirely possible that the land the donkey driver and his family now live on was handed to his ancestors by King Henri himself, after the revolution destroyed the sugar plantation system. The hectares of former plantations were often doled out to the families of those who had fought in the revolution.

Today, however, the guides who helped me up the mountainside were part of Haitis slow-growing tourist industry, showing off to the descendants of slaveholders the incredible antislavery monument their Haitian forebears had built and died building.

Next page