THE

FORGOTTEN

FLIGHT

THE

FORGOTTEN

FLIGHT

Terrorism, Diplomacy and the Pursuit of Justice

Stuart H. Newberger

Contents

Prologue

The Site

I CAREFULLY REMOVED the DVD from the hard plastic jacket and slipped it into my computer. The French documentary began a sober and quiet piece, with soft music and beautifully shaded photography. The pleasant tone did not prepare the viewer for the stark pictures, wandering snapshots of debris in the desert: huge aircraft engines crushed in the sand; passenger seats in clusters of four, tilting to one side; pieces of an aircraft fuselage lying in shallow graves. The severed cockpit juts out of the landscape, its small windows and aircraft nose pointing blankly into the sky. It resembles a death mask.

Much of the television program tracks the long, harsh ride of several SUVs as they convoy hundreds of miles into the barren desert landscape, riding over endless sand dunes and dry lakes. A few camels appear in the distance, led, as they have been for centuries, by Bedouins.

At a new construction site in the sands, workers place large black rocks in designated spots inside a two-hundred-foot-diameter circle. On its perimeter, the construction crew lay down 170 panes of glass, carefully set in concrete and then gently tapped into place with a hammer. The cracked glass creates a prism, diffusing the reflected sun in countless directions. At night, it will reflect the light of the moon and the stars.

As the film continues, a number of Bedouin workers haul an amputated section of an airplanes detached wing several miles in a flatbed truck. Working into the dark desert night, a few truck headlights guiding their efforts, the workers dig a deep hole in the sand and then, slowly and carefully, stand the wing on its thicker end, its narrow tip pointed towards the heavens. It stands erect next to the circle of black rocks, sand and broken glass prisms. A bronze plaque brought from Paris is mounted on the upright wing as the crew and workers stand respectfully in silence.

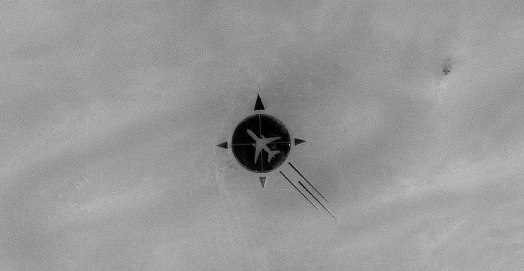

At this point, I click a few buttons on my computer to dial away from the documentary and switch screen to the internet. I hit a few more keys and a satellite map appears, showing the surface of the earth. It takes a few seconds for the imagea photograph of the planet taken from space, showing a circular structure spread out in the barren sandsto come into focus. The outline of a DC-10 wide-body jet, of authentic size, is etched into the landscape, its flight path frozen in the direction of Paris, north by northwest.

The silhouette of black rock, light brown sand and glittering ring of broken glass is easily viewed by anyone with access to the web.

The UTA Memorial, 25 June 2007 (courtesy of DigitalGlobe)

I stare at the screen for a long time. To me, the satellite image of the DC-10 is much more than a web-surfing curiosity. I had devoted nine years of my lawyering life to the very image in front of me. The story of how a life-sized memorial in the shape of a passenger jet came to be constructed in one of the most desolate places on the planet, and into which I had been drawn, is one of intrigue and drama, of international terrorism, diplomacy and the pursuit of justice. It had begun almost twenty years before the French film crew recorded the documentary I was now watching of the construction of the DC-10 Memorial and over ten years before I had been pulled into the grip of a case that would profoundly affect my life.

Over the years, the DC-10 on my screen had made hundreds of flights in the vast blue skies seven miles above the hot dunes of the Tnr desert in the south central Sahara, stretching from the northeast of Niger into Chad. But, as with many events that shape our lives, the story of the DC-10 Memorial began unexpectedly and was almost unnoticed.

Part I

Death in the Skies, Deals with the Devil

19892001

Chapter 1

19 September 1989

THE RADAR SCREEN was blank.

Flight 772 of the French airline Union de Transports Ariensknown by the large letters UTA, painted towards the front of the planehad taken off from NDjamena, Chad, at 12:18 GMT en route to Charles de Gaulle Airport, Paris. The DC-10 wide-body jet, a blue-and-white monster registered as N54629, was carrying 170 people, including its French crew.

The scheduled flight would take the aircraft high over the shifting brown sands of North Africa, crossing over Niger, Algeria and Tunisia. At the northern coast, the brown landscape below would morph into the shimmering blue water of the Mediterranean as the afternoon sun set on the right side of the plane. Reaching the south of France, it would begin to make a slow descent to Paris, the green manicured fields, hills and meadows coming closer into view in the fading light. The 4,236-kilometer2,632-miletrip would take almost five hours, not very long as intercontinental flights go, and the aircraft would undergo a fast turnaround at Charles de Gaulle before turning back to Chad and then heading due south to Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, where it would turn around again. This round-trip route between the French capital and two of Frances former colonies in North and West Africa was regularly filled with French businesspeople and diplomats attending to their duties in the French-speaking posts, Africans visiting friends and family long settled in Paris, and a variety of international travelers from around the world.

Captain Georges Raveneau, the pilot of the DC-10, reported to Chadian air traffic control at 12:34 GMT that the aircraft was flying steady over Niger at the time of contact. The Chadian control asked the pilot to contact the Flight Information Center at Nigers Niamey Airport at 1:10 GMT as Niger had no radar control sites. In this vast and sparsely populated part of the world, intercontinental pilots relied on their own navigation instruments between flight control centers. For most of an hour, the DC-10 was on its own, off any local radar coverage, as it flew due north toward the Mediterranean and Europe.

At approximately 13:10 GMT flight control in Niamey expected the UTA flight to appear on screen, its air speed at almost 400 knots and altitude 35,000 feet (10,000 meters), just as it had done twenty-four hours previously. Just as it had for several years of almost daily service. But the Niamey radar screen was blank, the neon green electronic arm making its clockwise pattern over the dark background.

No sign of the DC-10.

It was late.

A few minutes later, the Niamey flight control officer initiated standard procedures, sending its frequency to the overdue aircraft, calling other flights in the vicinity to see if the plane was somehow off course, checking for unusual weather, such as the violent dust storms that were a regular feature of the North African desert. Sometimes a really big storm could foul the radar coverage.

The radar screen was still blank.

At 14:15 GMT flight control issued its first formal radio call.

INCERFA phase. Uncertainty.

Under standard international call signs, this signaled that flight control was unsure of the location and status of the aircraft.

The radar screen was still blank.