CONTENTS

Introduction

Boora the Pelican

The First Kangaroo

The Sun-woman and the Moon-man

The Wedge-tailed Eagle, the White Cockatoo, and the Blanket Lizard

Yirbaik-baik and her Dogs

The Origin of Fire

Goolagaya and the White Dingo

The Death of Jinini

The Men of the Milky Way

Koobor the Drought-maker

The Banishment of the Cuckoos

Tiddalik the Flood-maker

The Storms of the Willy-wagtail

Purupriki and the Flying Foxes

Tirlta and the Flowers of Blood

Bima the Curlew

The Numbakulla and the First Aborigines

The Frogs and the Sound of Wind

Mangowa and the Round Lakes

Inuas Ladder

The Seven Emu Sisters

The Lightning-man Wala-undayua

The Woma Snake-man

Wuluwait the Boatman of the Dead

Mirram and Wareen the Hunters

The Creation of the Eagle and the Crow

The Frog-woman, Quork-quork, and her Family

The Mopaditis and the Black Cockatoos

The Transformation of Parabruma

Ulamina and the Stolen Canoe

The Native Cat, the Owl, and the Eagle

The Bailer Shells, the Dolphins, and the Tiger-shark

THE DREAMTIME

Australia is an ancient land, undisturbed by any major geological upheavals for many millions of years. Its people, too, are an ancient people, who, reaching the shores of this continent fifteen thousand or more years ago, were able to follow their simple way of life until we, the white intruders, came among them.

No other race has ever lived in Australia, nor at the present time are there people of the same stock anywhere else in the world, except, perhaps, the pre-Dravidians of India, and the almost extinct Veddahs of Ceylon, who may be distantly related.

There is no evidence that the Australian natives originated in their present homeland; but, wherever they came from, it is reasonable to assume that they left south-eastern Asia and travelled to Australia through the Indonesian and Melanesian Islands, their journey spanning probably many hundreds of years.

Although Cape York, on the north-eastern corner of the continent, would have been the easiest and most reasonable point of entry, some groups may have landed along the north-western coasts of the continent. Irrespective, however, of their points of entry, these brown-skinned people were living in every part of Australiafrom the fertile, well- watered coastal regions, to the arid, inhospitable interiormany thousands of years before European settlement reached their homeland.

It is certain that the aborigines have always been, as they are today, simple hunters and food-gatherers, collecting their sustenance at such time and place as Nature provided. In seasons of plenty they feasted, and in times of hardship they philosophically endured hunger, confident that some foods would soon be ready for harvesting.

The equipment of the aborigines is particularly limited. Except along the coastline, or on the larger rivers, where fishing is an activity, the men own little more than spears, spearthrowers, boomerangs, and clubs; and the women use wooden, bark, or string containers, grinding-stones to reduce grass-seeds into a coarse flour, and simple digging-sticks for unearthing tubers and small creatures.

Some tribes use simple watercraft, but over the vast stretches of the Australian coastline the aborigines are without any means of travelling by water. They do not know how to weave cloth to cover themselves, have no pottery techniques by which to make cooking vessels, nor any beasts of burden on which to travel or carry goods. From the standpoint of material possessions the aborigines of Australia are, without doubt, the poorest of any people.

This material poverty has led to the mistaken impression that, as the white man uses so many, and the aborigines so few tools with which to gain a livelihood, the aborigines must have the lesser intelligence. But this idea is completely refuted on an examination of the success of the food-gathering of the aborigines in the almost waterless deserts of central Australia, a country so arid that no white man can live there unless he takes his own food.

Yet, with no more than five tools, the aborigines have been able to live and multiply in this harsh and unfriendly country for many centuries. This is surely evidence not only of normal intelligence, but of minds intensely trained in the lore of the desert, and in the knowledge of its food resources.

The aborigines live in family groups, each group having its own territory, which its members seldom leave, except to attend some important ceremony, or when there is a shortage of food or water. All members of the family, from children to the oldest men and women, engage in a continuous search for food, a search that must go on from day to day, for they have no means of storing or preserving what they kill or collect.

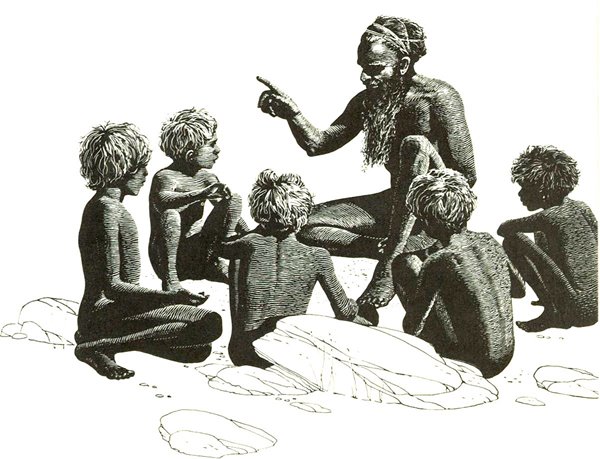

To meet these conditions, the natives must acquire a profound knowledge of the rhythm of their country. From early years they learn when the vegetable foods ripen, and where they may be gathered; the seasons of the year when the reptiles wake from their winter sleep, when the animals reproduce, and in what place there will be water to drink.

The aborigines have also developed a calendar, based on the movements of the heavenly bodies, the flowering of certain trees and grasses, the mating calls of the local birds, and the arrival of migrant ones. All these signs are related to the food-cycles on which their living depends.

The labour of food-gathering is fairly equally divided between the men and the women. To catch the larger creaturesthe kangaroos, the wallabies, and the emusthe men often have to make long journeys in the cold of winter or the blazing heat of summer. The women, laden with the children and the camp gear, travel in a more or less straight line from one stopping place to the next, gathering vegetable foods, fruits, and small creatures on the way. The men often return empty- handed at the end of the day, for the desert animals are wary and difficult to capture, but the women always bring in some food. Sometimes it is not much, nor particularly tasty, but it is usually enough to keep the family going until the hunters are more successful.