morbo

Phil Ball began life in Vancouver, was brought up in Cleethorpes and ended up in the Basque Country, after spells in Peru and Oman. He has written for When Saturday Comes since 1987 and lives with his partner and two children in San Sebastin. He is also the author of White Storm: 100 Years of Real Madrid and An Englishman Abroad: Beckhams Spanish Adventure.

morbo

The Story of Spanish Football

Phil Ball

First published in 2001 by WSC Books Ltd

This edition published in 2011 by WSC Books Ltd

The Old Fire Station, 140 Tabernacle Street, London EC2A 4SD

wsc.co.uk

info@wsc.co.uk

Copyright Phil Ball 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publishers. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers consent in any form of binding other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. The moral right of the author has been asserted.

ISBN 9780956101129

Cover design by Doug Cheeseman

Printed by MPG Biddles www.biddles.co.uk

To the three Ds

David, Doris and Diana

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following for their help.

David Lindsay, Juanjo Moran, Juan Bautista Mojarro Garca, Toni Strubell, Duncan Shaw, Simon Inglis, Maite Ibaez, Joaquin Bueno, John Mills, Angus MacDonald and everyone at When Saturday Comes who has worked on the various editions of the book: Mike Ticher, Andy Lyons, Doug Cheeseman, Richard Guy, Shane Simpson, Ed Upright and Paul Campbell.

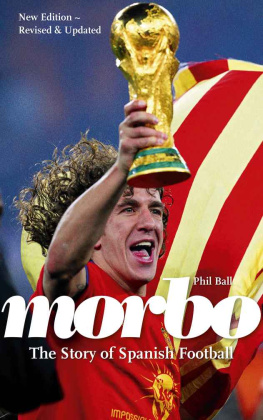

Front cover

Carles Puyol of Spain, and Barcelona, celebrates winning the 2010 World Cup in South Africa against the backdrop of a Catalan flag. Getty Images

Back cover

Athletic Bilbaos Iker Muniain (right) is congratulated by David Lpez during the Basque derby with Real Sociedad in 2011 as the Ikurria , the Basque national flag, flies in the background. Getty Images

contents

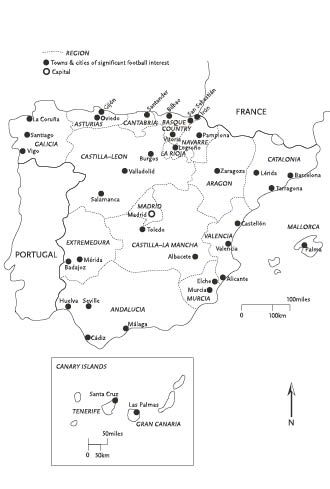

Map of Spain 8

Note on foreign usage 9

Introduction 11

1. morbo

2. brave and bold 39

Huelva, birthplace of Spanish football

3. the quarrymen 61

Athletic Bilbao and the politics of the Basque Country

4. sunshine and shadow 84

The ambiguous truth about Barcelona

5. white noise 119

Madrid and the legacy of Franco

6. five taxis 154

Seville s healthy rivalry

7. morria 174

The unexpected challenge from Galicia

8. a fire in the east 191

Valencia s hard road to the top

9. yokels, cucumbers and mattress-makers 202

Spanish club culture

10. dark horses no more 218

Spain reigns supreme after decades of failure

11. new order? 246

The limits of democracy

Appendix 252

Index 256

spain

Note on Spanish, Catalan and Basque usage

Certain words appear in different guises in this book for distinct reasons. The Barcelona-based club Espanyol have officially spelt their name in Catalan since 1994, using the y instead of the previous Castilian , as in Espaol. The spelling appears in the latter form when the text refers to the clubs pre-1994 story, for reasons of historical coherence.

The spelling of Barcelonas former president Josep Sunyol is in Catalan, in spite of family objections (see page 105). The same clubs founder, the Swiss Hans Kamper, changed his name to the Catalan Joan Gamper a change that is respected in the temporal progress of the chapter on Barcelona. In other cases, Catalan is used wherever it is appropriate.

The spelling of the city Seville and of the football club of the same name is differentiated in order to distinguish between the two. The English spelling Seville is employed for the city, and the Spanish spelling Sevilla refers to the club.

Basque place names have not generally been used, for the simple reason of familiarity. San Sebastan is known as Donostia in Basque, Vitoria as Gasteiz and so on, but it would have been unnecessarily unwieldy to have included all this information in the flow of the text. The Spanish versions are merely employed as terms of general convenience and not as political statements.

introduction

When I was a kid, I saw an item on the news one tea-time about the running of the bulls in the fiestas of Pamplona. I was at that age when you didnt really listen to the news, but just looked up at the screen from time to time as you ate your scrambled eggs. I never questioned what I saw on that night long ago, but the madness of the scene etched itself into my memory in that twisted, dreamy sort of way it does in childhood, and I spent the subsequent years convinced that the Spanish ran through the streets of their country on a daily basis, pursued by fearsome bulls.

So convinced was I that the natives spent their days peering gingerly from left to right as they stepped from their doorsteps that I could not bring myself to ask several schoolfriends, whose parents had actually taken them on holiday to this curious country, how they had coped with that particular inconvenience. I preferred not to know. The idea was enough, and, as with the death of Santa Claus, the truth would have proved simply too mundane. I never dreamed that one day I might come to live in and write about this same country and that my own children would be born there half an hours drive from Pamplona. And the madness I thought I saw all those years ago is certainly here, albeit in a different guise.

This book is about Spanish football, but it is not football which defines the peculiar character of the country. Within the European frame, Spains has always been one of the most difficult cultures to paint. It has always been a state of mind, not just for the British but for the rest of Europe as well, despite the shift in perception that has taken place in recent years as to the desirability of maintaining all those corny cultural stereotypes we grew up on.

Most people probably know now that Spain is really a loose federation of fiercely autonomous regions, and that in only one of them do people actually waft fans and dance sevillanas with any sort of regularity. But deepest Spain is still a strange beast, way beyond the one that is now packaged for the British middle-classes. As VS Pritchett wrote back in the 1950s, Spain breaks with Europe whatever that is when you pull up at its frontier:

England is packed with little houses; France lies clearly like green linoleum, a place of thriving little fields; but, cross the dark blot of the Pyrenees and Spain is reddish brown, yellow and black, like some dusty bull restive in the rock and the sand.

Plenty of writers have made similar observations about Spain, that it is somehow out on a limb, isolated, literally down there. When you live there for any length of time you begin to feel that the rest of the world is beginning to melt away. The newspapers have their international sections, but they read like a reluctant afterthought. In any case, Spain has almost the lowest percentage of newspaper sales per head of population in Europe. People lead their own lives here, and the rest of the world can get on with whatever its getting on with.

In some ways, its a much odder place in reality than it seemed to me back then as a kid. Many Spaniards are still formal and conservative in both dress and manner, but at the same time wildly anti-authoritarian, giving the poor police and referees a hard time of it. Smoking was finally banned in bars in 2011 after predictably vehement protests. The Spanish find rules problematic. Men, women, children and grannies all swear like proverbial troopers, invoking their muse to soil every garment of Catholic sensibility imaginable, only to dress up like Lord and Lady Muck on Sunday morning and stride head-high to church as if the Lord had never heard them. Guilt is a grey area, and is consequently a no-go zone for the Spanish. Pity the poor outsider who dares to throw into a conversation a mere suggestion of doubt. He or she will more than likely be howled down. To the average Spaniard, publicly at least, there is black and white, and anything in between is the stuff of the limp-wristed and the feathery.