Table of Contents

ALSO BY JIMMY BURNS

Papa Spy

When Beckham Went to Spain: Power, Stardom & Real Madrid

Barca: A Peoples Passion

The Hand of God: The Life of Diego Maradona

The Land That Lost Its Heroes: How Argentina Lost the Falklands War

Beyond the Silver River: South American Encounters

Spain: A Literary Companion

For Kidge, Julia, and Miriam

PREFACE

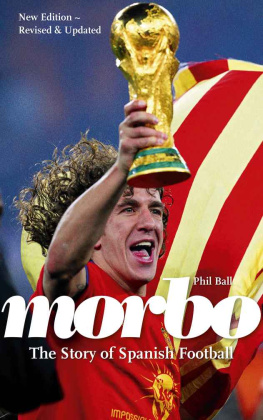

The human wave started in a town in South Africa, watched by a worldwide audience of more than a billion people, and gathered force as it swept up the continent, before crossing the Mediterranean and rolling across the stark landscape of CastileLa Mancha and crashing onto the streets of Madrid. The heat and dust of a suffocating local summer were refreshed by sheer human effervescence, as more than a million Spaniards filled the center of the Spanish capital, celebrating the return of their heroes, the winners of the 2010 Soccer World Cup.

After being honored by King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofia at the royal palace, the players boarded an open-roofed double-decker bus and began a slow progress toward the banks of the Manzanares River. The route took them from the palace of the prime minister, Jos Luis Zapatero, and through the Plaza de Espaa, the square that has at its center a monument to Cervantes, creator of Don Quixote. In that short journey, the character of a nation seemed defined.

Throughout its turbulent history, pockmarked with foreign invasions, coups, and civil wars, Spain has had its fair share of great and disastrous monarchs, political leaders, and failed missions. But whereas Zapatero was once a popular socialist leader who was on his way to being politically sunk by his administrative incompetence in the face of Europes financial crisis, King Juan Carlos endured as a symbol of national reconciliation. It was this king who had assumed the role of head of a democratic state after the death of the dictator Franco in 1975 and resisted an attempted army coup six years later. This defiance of the army was in startling contrast to his grandfather Alfonso XIII, who in the 1920s had passively accepted the bloodless uprising of General Miguel Primo de Rivera. Perhaps the most significant aspect of the 1981 coup was not that it happened but that it failed. Spaniards woke up to the benefits of democracy and rallied around it. Spain had changed irrevocably since the dark days of Franco, and there was no turning back. Yet it was the statue of the fictitious literary figure Quixote that still served as a reminder that this was a nation personified in a hero whose nobility and achievementso celebrated by Spanish philosophers seeking to place their country on a moral and political pedestalproved delusional.

In the lead-up to Spains bloody civil war in 1936, Manuel Azaa, the then president of the Second Republic, remarked that in the defeat and disappointment of Don Quixote was the failure of Spain itself. He might have addedwith an eye to the futurethat Spains soccer had for much of its history also mirrored its politics, touched as it was with its tales of individual brilliance, occasional collective effort, but ultimate underachievement of the national squad in contrast to the international success of rival clubs. Yet in the summer of 2010, beyond Quixotes statue, thousands lined the streets and avenues before closing in as the victory bus made its slow progress, each individual citizen stretching out their hands in collective admirationor, rather, making sure they were not dreaming.

This was no ordinary homecoming. For starters, the celebrations extended across the country, from Seville in the South to Barcelona in the North, a reflection of the rich mix of regional identity represented by the champions. In the Basque Country, where the terrorist organization ETA was still waging a bloody campaign for independence from Spain, a shopkeeper was beaten by thugs for celebrating the teams victory, while right-wing Spanish patriots covered a statue of a Basque nationalist politician in the red and yellow of the Spanish flag. In Catalonia a few radical Barca fans who also wanted independence from Spain refused to watch the World Cup and staged a counterdemonstration. But these were isolated incidents. The pervading image was of an explosion of Spanish flags all over the country, even in the most nationalistic anti-Spanish neighborhoods, as if the shared and successful enterprise in soccer had for a moment at least set aside the seemingly irreconcilable political, social, and cultural prejudices that had separated Spaniards from different regions and backgrounds for much of their history.

This was not only the first Spanish team to win the World Cup in the tournaments history but one that had done so with an artistry that many believed represented the best soccer ever played. La Roja, the Red One, was how the team had been nicknamed. The name was aired almost as a matter of fact in an early press conference given by Luis Aragons, the national coach under whose command a new creative and winning style of soccer came to be played by Spain in the run-up to its victory in the European Championship of 2008. Red had been one of the main colors of shorts and shirts worn by the national squad as long as most Spaniards could remember; only politics had seemed to get in the way of accepting it as a brand like, say, the Azzurri in Italy or the Bleus in France. When he used the word, Aragons felt that enough water had flowed under Spains political bridge for Spaniards to call a spade a spade, or a teams gear by its proper color. But even in 2008, those old enough to remember the civil war and to have supported Franco found Aragons provocative. To be a Rojo in the civil war was to be anti-Franco, and whereas Real Madrid played in white, Barca had red in its colors and the Catalan more red stripes than the Spanish flag. As for Zapatero, Real Madrid fans were not pleased to have in power the first Spanish prime minister ever to declare himself publicly a Barca faneven if he was born in the very Castilian town of Valladolid.

The summer of 2008 was the honeymoon period of the Zapatero socialist government, prior to the global banking crisis detonated by the collapse of Lehman Brothers. That spring Spains Socialist Party had again triumphed in elections, giving Zapatero a fresh mandate to pursue his agenda of sweeping social, political, and cultural reform. Despite a bitterly fought campaign, the election victory appeared to endorse Zapateros boldest decisions, such as the withdrawal of Spanish troops from Iraq, the granting of more autonomy to the regions, and the legalization of homosexual marriage.

The future looked red. To that extent, Aragons stood accused of political opportunism by certain elements of the Right. But then Aragons was not a politician. In fact, he had a reputation for saying what he felt like when he felt like saying it, however politically incorrect, as when he incensed the English media with his racist jibes against English black players. But somehow La Roja caught on and grew in popularity, not because of Aragons but despite him (before the World Cup campaign was under way, Aragons had been replaced by Vicente del Bosque), as if the term appealed subconsciously to a national mood, of marking the point at which Spain had moved from being a failed state to being a civilized nation, which could also be good at soccer and find in this a sense of common purpose.