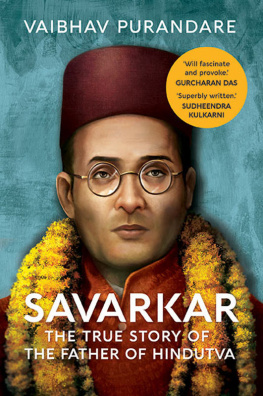

Savarkar

Praise for the book

A lively, well-researched, and balanced account of a hugely controversial figure. Full of rich, moral ambiguity, it will fascinate and provoke even if you dont agree. Gurcharan Das

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was controversial, while he was alive, and remains so, even after his death. Strong in his convictions (the manner of his death is an example), he inspired, but perhaps did not always endear. His political differences also explain why he did not always get his due. Vaibhav Purandare has written a wonderful biography, based on a considerable amount of research. Veer Savarkar truly comes alive, a product of his life and times, not easily compartmentalized into black or white. For those prone to clichs and stereotyping, an extremely balanced book. Bibek Debroy

Superbly written and deeply researched, this book is neither hagiographic nor does it suffer from unbalanced criticism. Vaibhav Purandares portrayal of Savarkars life and politics shows us a revolutionary freedom fighter who, sadly, became the ideologue of divisive Hindutva, with the needle of suspicion forever pointing at him for his involvement in the plot to kill Mahatma Gandhi. Sudheendra Kulkarni

Savarkar

The True Story of the Father of Hindutva

Vaibhav Purandare

JUGGERNAUT BOOKS

KS House, 118 Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110049, India

First published by Juggernaut Books 2019

Copyright Vaibhav Purandare 2019

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

P-ISBN: 9789353450526

E-ISBN: 9789353450557

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro by R. Ajith Kumar, Noida

Printed at Manipal Technologies Ltd

For Swapna and Vikrant

Contents

In December 2018, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) visited Cellular Jail on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, where scores of Indias freedom fighters were once incarcerated for long periods by the British government. This was a place of pilgrimage for him, Modi said: after all, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, ardent nationalist and revolutionary, had spent a whole decade in a damp cell there. As a product of the Hindu nationalist movement, Modis sense of nationhood is underpinned by Savarkars theory of Hindutva or Hinduness, and so is his idea of sinewy national self-assertion and a foreign policy based not on an abstract dream on the distant horizon but on realism and realpolitik. Thus, once inside Savarkars cell, Modi took on the posture of a pilgrim. He sat cross-legged on the floor, eyes shut in a prayerful, meditative way, in front of a photograph of Savarkar that has been kept there the devotee invoking silently, inside the sanctum sanctorum, the image of his presiding deity.

At around the same time, Rahul Gandhi, the scion of free Indias longest-ruling dynasty, the NehruGandhis, was mounting a sharp attack on Savarkar, labelling him as someone who wrote letters of abject apology to a foreign ruler simply to be able to get out of prison; the Rahul-skippered Congress even described Savarkar as a traitor. Rahul contrasted Savarkars approach with that of Mahatma Gandhi and of Indias first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, who, he said, had never given in to British bullying despite all the hardships they faced in so many jails.

When Savarkar died in 1966, he was on the fringes of Indian politics and was an ignominious figure, having been arrested and named as an accused in the plot to assassinate Gandhi. His infamy in the Gandhi murder case and his relative political obscurity would remain undisturbed in the future, it was believed.

Savarkars political resurrection in the new millennium and the robust revival of his story and myth are, therefore, remarkable. The resurrection actually began in the mid-1980s, when Hindu nationalism, for long dismissed as a marginal and spent force, suddenly burst on the Indian scene with the BJP and its leader L.K. Advani championing the cause of religious identity. After the Indian experience of BJP governments led by A.B. Vajpayee, which nudged India into the new century on the back of nuclear tests and an intense IndiaPakistan armed conflict, and especially since Modis emergence amid communal violence in Gujarat in 2002 and his subsequent rise to the prime ministers post, Savarkars Hindutva has unleashed the kind of political energies it was never really expected to.

With his brand of nationalism gaining so much ground and at least momentarily eclipsing the Nehruvian social and political template that once appeared impossible to supplant in a pluralistic society, the historical figure of Savarkar now looms large in the Indian political landscape. In fact, his prominence in the realm of public debate today is far more striking than it had been at several points in his own chequered life. Not since 1966, when Dhananjay Keers biography of Savarkar was published in the year of Savarkars death, has there been a full-length biography of the man in English. A fresh look at his life, especially given his prominence in India today, is in order.

A man of extremes, Savarkar also evokes extreme reactions. The most fervent commentary on Savarkar is centred principally on four points: his status as freedom fighter owing to mercy petitions he wrote to the Raj from Port Blair, his advocacy of Hindutva, his opposition to the Quit India movement and his alleged role in Gandhis assassination. We will come to each of these turn by turn.

Savarkar was given two terms of life imprisonment by the British Raj, and they were meant to run consecutively and not concurrently. Life imprisonment then meant twenty-five years, so he was to spend fifty years in jail in all. He was dispatched to the Andamans and was incarcerated there for ten years, from 1911 to 1921. During this time he wrote at least seven petitions asking for mercy and requesting an early release.

To cry cowardice and surrender, to call him a traitor, or to say he was begging for mercy from the British while Gandhi was sleeping on the dirt floor of a jail is unwarranted and puerile. While he was in prison, Savarkar was tortured in the most abominable, medieval ways. He was put into solitary confinement for long stretches of time. He was deprived of food and water and made to do hard labour; he would faint from exhaustion but still wasnt given reprieve from work. He was chained to a wall, hands extended above his head, for hours at a stretch on consecutive days. During these spells, he was not even allowed to go to the bathroom to relieve himself and had to stand in his own filth chained to the wall. Is it really fair to judge what a person says or does under such conditions of inhuman torture?

Savarkar, by the way, was not the only one to submit such mercy petitions. His fellow prisoner and revolutionary Barindra Kumar Ghose, Aurobindo Ghoses brother, did so, as did Satyendranath Bose and many other celebrated Indian rebels, not merely in the notorious Cellular Jail of Kaala Paani but in comparatively milder prisons on the Indian mainland as well. In the late 1920s, for instance, many of the widely revered revolutionaries convicted in the Kakori conspiracy case involving an attack on a train carrying government funds, including the protagonists of the attack Ramprasad Bismil and Sachindranath Sanyal, wrote mercy pleas. Thankfully we do not brand them as traitors. Savarkar certainly does not deserve singling out on this count.

While Savarkar was seen as a fringe player towards the end of his life, he started out as a fearless and pioneering anti-colonial crusader. He called for complete independence from the British Raj at least twenty years before the Congress did so in its resolution of 1929. Savarkar called for Purna Swaraj at a time when Indias most enthusiastic nationalists were submitting mild representations to the Raj, at most pushing for greater representation on the central and provincial law-making councils or for home rule, which meant self-government or responsible government under the overarching umbrella of a sunset-defying Empire. This does not make the one greater and the other less great, for the Congress, under Gandhi, was the biggest mass organizer of the liberation movement. But Savarkar was among the earliest to push the boundaries and propel the national movement towards its chief goal.

Next page