Introduction

Imagine an individual ranged against an empire. If that sounds like a grossly unequal situation, imagine that the empire is among the worlds biggest and most powerful of its time. You would think the imbalance of power would be too great for even a semblance of a serious contest.

However, the Maratha Shivaji Raje Bhosle, son of Jijabai and Shahaji Raje Bhosle, did not merely put up a fierce fight against the mighty Mughal empire when it was at the height of its glory under its sixth emperor, Aurangzeb, in the seventeenth century. He actually sparked a movement that coursed through the Deccan and sowed the seeds of the empires fall and destruction. In the process, Shivaji set up his own independent state, anointing himself Chhatrapati bearer of the chhatra or royal umbrella. He fashioned his own template of governance and of political and revenue administration, framed policies of responsible and responsive conduct for the new states officials, both civilian and military, and gave robust expression by way of words and actions to values of religious plurality at a time when Aurangzeb was actively and aggressively distorting those values.

Chhatrapati Shivaji is a singular figure in the early modern history of India because he shaped a political revolution in his native Deccan which had implications for the entire map of the Mughal empire, which included in its sweep Afghanistan in the north-west and Bengal in the east. When he was born in 1630, the western part of the Deccan he came from had three Islamic sultanates: the Nizam Shahi of Ahmadnagar, the Adil Shahi of Bijapur, and the Qutub Shahi of Golconda. While all three were constantly warring, the Mughals, ever increasing in strength, were pressing in from the north in a bid to conquer the southern parts and wipe out the sultanates. The constant warfare of these four kingdoms caused huge turbulence in the Deccan, unsettling populations and fitfully shifting the contours of its politics. The Marathas of the western Deccan had emerged as highly competent military personnel in the sixteenth century, but they were engaged entirely in serving one or the other of these four powers, either as generals who took and implemented orders or as foot soldiers.

Shivajis father, Shahaji Raje Bhosle, was a military general of note. He played a stellar role in propping up the Nizam Shahi Sultanate in its last years in the 1630s; he had, besides, important stints with the Adil Shahi rulers of Bijapur and also a short one with the Mughals. Astoundingly, Shivaji launched his rebellion in his teenage years by capturing four hill forts belonging to Bijapur. He later had to backtrack to save his father but continued to swim against the main political current of his times, which was, for the Marathas, to join one or the other well-established kingdoms. He persisted with his rebellious actions, forming a solid, cohesive bond with the ordinary, nameless people and peasants of the hills, and winning friends and comrades who would help him raise the political structure he was seeking to create. His opponents realized that though he was an outlier, the Maratha rebel was a clear and present threat because of his natural charisma which always disarmed people his smart strategizing, his military skills and his leadership.

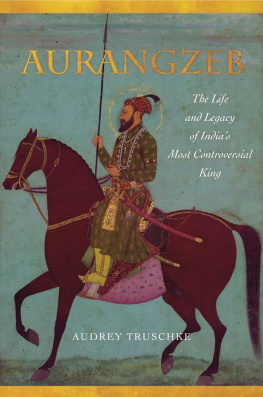

Aurangzeb was on top of the world at the time Shivaji attacked his territories but as a sharp and alert military commander himself, he was not dismissive of Shivaji. Just like Bijapur had done before him, he publicly called Shivaji all sorts of names, describing him as a mountain rat, yet immediately directed the full might of the empire against the emerging rebel. Aurangzeb was acutely conscious that Shivajis greatest strength lay in his hill forts and treacherous terrain and that he was deploying the Maratha guerrilla playbook devastatingly against his opponents. It was a captivating contest between two superbly pitted rivals, Shivajis insurrection growing in size even as Aurangzeb repeatedly applied an incredible amount of pressure and the Mughals vastly outnumbered the Marathas.

Broadly, Shivajis career had three stages. The first was from his childhood until 1656, the first twenty-six years of his life. It was marked by his early deeds as a rebel. The second phase covered the dramatic decade from 1656 to 1666. The battle of wits and the action during these ten thrilling years, as Shivaji took on both Bijapur and Aurangzeb, were extraordinary. From time to time, Shivaji suffered setbacks as the confrontation raged, and there were points when he found himself staring at an abyss and things looked hopeless for him. The manner in which he picked himself up and hit back at both the Adil Shahi and the Mughals makes this decade one of the most fascinating in the history of early modern India. The third phase from 1666, when Shivaji was thirty-six, until his death at the age of fifty in 1680 combined consolidation and expansion even as the conflict between Shivaji and Aurangzeb played out relentlessly, capturing attention across the length and breadth of India.

Shivaji was shrewd enough not to engage in pitched battles with his enemies. This allowed him to calibrate his stand and take the measure of his opponents before he made his responses. He also offered concessions to his opponents and made retreats in order to give himself time to re-equip himself and his forces and to make further gains on the ground. One of his outstanding qualities as a military leader and statesman was that he was as brilliantly adept at holding himself back as he was at launching the most boldly daring and seemingly impossible of attacks.

Among the things that left Shivajis opponents flummoxed was the steadfast loyalty of his lieutenants and followers, mostly people drawn from ordinary families in the Deccan. One of his closest aides, Baji Prabhu Deshpande, held off a major Bijapuri onslaught in 1660 in a narrow pass in the mountains with a group of just 300 men to enable Shivaji to reach a place of safety; in the process Baji Prabhu laid down his life, becoming a legend in his own right.

In 1674, Shivaji took the momentous decision to crown himself sovereign, a declaration of the establishment of his own independent state, and in heraldic terms, the start of a new era. By giving his rule legal, official status, he robbed Aurangzeb, Bijapur, Golconda or anybody else for that matter of the opportunity of accusing him of overstepping the line. From now on, he was going to deal with them all as an equal. He had pulled off something that hardly anyone could match up to.

At the time of his death in 1680, when he was only fifty years old, Shivaji had left for his successors such a wealth of inspiration that despite Aurangzebs hurried march to the Deccan to recapture lost ground, they succeeded in ensuring that the Mughal emperor stayed in the south and could never go back to the north for a quarter of a century, up until his death in 1707. In the first half of the eighteenth century, the rule of the Marathas reached its apogee as they conquered the major part of the subcontinent, their territory stretching from Attock in the north (in present-day Pakistan) to Bengal in the east before the British came and took over.

One of Shivajis most remarkable achievements was the building of his own naval fleet. He was alone among his contemporaries in recognizing the importance of the seas and demonstrated a political and strategic vision in this regard that all the other rulers sorely lacked. The foreign powers the Portuguese, the Dutch, the British and the French were reluctant to share sea power with him. In fact, they often showed open hostility, and Shivaji had to nuance his positions with them, alternating between demonstrating his strength and opening negotiations. Shrewd general-statesman that he was, he was as deeply wary of and sceptical about the firangs as he was about all of his other adversaries. He remained constantly alert to their shenanigans, took forceful, uncompromising and retaliatory actions where necessary, and reminded them constantly that they would have to accept things on his terms a quality that stands out given the rapaciousness, especially of the British East India Company, that revealed itself later on and proved costly to the people of the subcontinent.