To Susan Olds, Mark Di Ionno, Wally Stroby,

Rosemary Parrillo, Anne-Marie Cottone,

Jenifer Braun, Steve Hedgpeth, and the rest

of the gang from the glorious 90s heyday of

the Star-Ledger features section.

Love,

Kid & Genius

Contents

The Foreword:

You Get What You Pay For

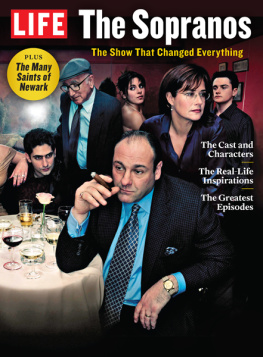

Before 2002, I had seen exactly one episode of The Sopranos, a chance encounter in an upstate New York motel room. I liked what I saw, but I had been raised by thrifty parents with a long list of things one should never pay for, and premium cable was at the top. Never mind basic cable; television was meant to be free. So in 1999, I watched that one episode, then let The Sopranos go. Three years and three critically acclaimed seasons later, all I knew was that Tony Soprano once took his daughter on a college visit and things did not go as planned.

Then I decided to buy a house with my then-boyfriend, now-husband, who happened to be making his own HBO show, The Wire. (In fact, he was so busy filming that I was alone on moving day; lets not revisit that old grudge.) Our new house had green laminate kitchen counters, just like Carmela Sopranos. More thrillingly, we had an HBO subscription and a nice cache of free DVDs. So when oral surgery sidelined me for a couple of days in spring 2002, I made myself a cheese souffl and started my first binge watch, although that term was not yet mainstream. My hope was that The Sopranos would distract me from my pain until I could fall asleep.

I knew very little sleep over the next three days.

Like millions before me, I was hooked, showing up every Sunday night for the three seasons that aired over the next five years. (Like the writers of this book and David Chase himself, I count them as four seasons.) After it ended in 2007, I rewatched the series in full at least six times.

Serial dramas are now commonplace, yet few equal The Sopranos. One can watch it start to finish with enormous satisfaction, yet also enjoy single episodes with almost no context. Toward the end of my fathers life, when his memory was failing, he happily watched the bowdlerized episodes on A&E the way his father had once watched Perry Mason. No matter that he couldnt remember the larger plot arcs; the individual shows never failed to entertain him.

I credit this quality to Chases years on relatively traditional Hollywood fare, like The Rockford Files and Northern Exposure. He has an incomparable short-game/long-game approach to making television. There is a form in fiction that many claim, but few actually deliver: connected short stories in which the whole transcends the parts. The Sopranos works that way. Episodes we think are one-offs still carry important pieces of the story; plot-heavy installments can be enjoyed in isolation.

Consider Pine Barrens. It may feel like a bottle episode, but the animosity between Paulie and Chris will surface again and againtheir secrets from that day endure. Or take College, my first tasteas Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall tell us in this book, the episode where The Sopranos became The Sopranoswhich makes the counterintuitive choice to have Tony in Maine while Carmela entertains the parish priest back in New Jersey. You cant subvert a genre until you understand it. Chase and his writers clearly knew all the ins and outs of Mafia movies, but they also recognized that their characters would, too. These wise guys were not only in on the jokethey made jokes.

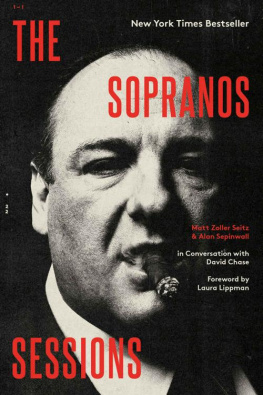

Eventually, I became a little bit of a Sopranos obsessive. That might sound like an oxymoron, but when you read this book, you realize that there are levels of Sopranos obsessiveness. The trivia I so proudly identified during rewatchesLook, theres Joseph Gannascoli, who will later play Vito Spatafore, as a civilian-schmo day player in season oneare nothing compared to the details that Sepinwall and Seitz have mined here.

Speaking of our guideswhile I have a vivid memory of my first Sopranos encounter, I am less clear when I started to read Alan and Matts work, but I know it goes back more than a decade. It was probably through their excellent commentary on and recaps of The Wire. But I have continued reading them because of their intelligent overall enthusiasm for television. I love television. I have always loved television. Even as a child, I knew there was something fundamentally wrong with the snobby woman on The Dick Van Dyke Show who, upon meeting Rob Petrie, trilled, Oh, I dont own a television machine. The number of good television critics in place when The Sopranos first aired is a testimony to newspapers (which I also love). But I think Alan and Matt are particularly exceptional in their approach to this groundbreaking show. Its hard to imagine that anyone has thought this long and hard about these episodes, unless its David Chase, his writers, and the late James Gandolfini.

A burning question hangs over this enterprise: What about that finale? I dont want to give anything away, but I will say that The Sopranos Sessions provided me withoh dreaded wordclosure. I watched Made in America alone, my husband thousands of miles away in South Africa, filming an HBO miniseries. (Please note the motif of HBO taking my husband away when I need him most.)

When the screen went black and the sound cut out, I was convinced there had been an outage. In May 1998, there was a power failure in Baltimore just before the Seinfeld finale that knocked out cable to thousands, so perhaps I was oversensitive to the likelihood of it recurring.

Once I realized the dead screen was intentional, I felt, well, mocked. I had logged serious time with The Sopranos. I had even attended the premiere for season fours first two episodes, memorable because I sat in front of William Styron, who laughed heartily at the scene in which Adriana vomited so violently that her poodle ran for cover. I wasnt some bloodthirsty mook cheering for more whackage. I was a serious, thoughtful fan who could recognize William Styron at Radio City Music Hall. I wanted and deserved a great ending, like the montage to Thru and Thru in Funhouse, the season two finale. By then Id written seven books in a series of crime novels about a Baltimore PI, and I believed that if I ever chose to end my series, I would do it with a grand, reader-rewarding flourish. My feelings about the Sopranos finale joined a list of passionate grudges that includes the 69 Super Bowl, the 69 World Series, and the HBO executives who scheduled production of my husbands latest show to coincide with my book tour.

In all seriousness, this book helped me heal. I now understand that Chase was in a dilemma not unlike L. Frank Baum, who wanted to stop writing about Ozthe original Oz, not the HBO onebut faced an insatiable appetite from young readers. At one point, Baum went so far as to make Oz invisible to the world and had Dorothy Gale, now a permanent resident, send a note: You will hear nothing more about Oz, because we are now cut off forever from the world. It didnt work; Baum would write eight more Oz books, and other writers continued the series long after his death. Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back insound familiar?

How does one resolve the problematic story of Tony Soprano, a monster that millions welcomed into their homes for eight years? It wasnt Chase who made a fool of me, but Tony, who had done the same thing to Dr. Melfi. But unlike Dr. Melfi, I was never going to have the resolve and discipline to turn my back on him. The scene in Holstens, which had felt like such a fuck-you at the time, now seems like one of the more definitive endings in the history of television.

Next page