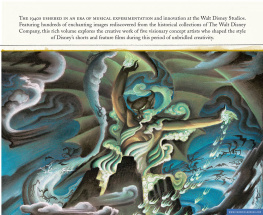

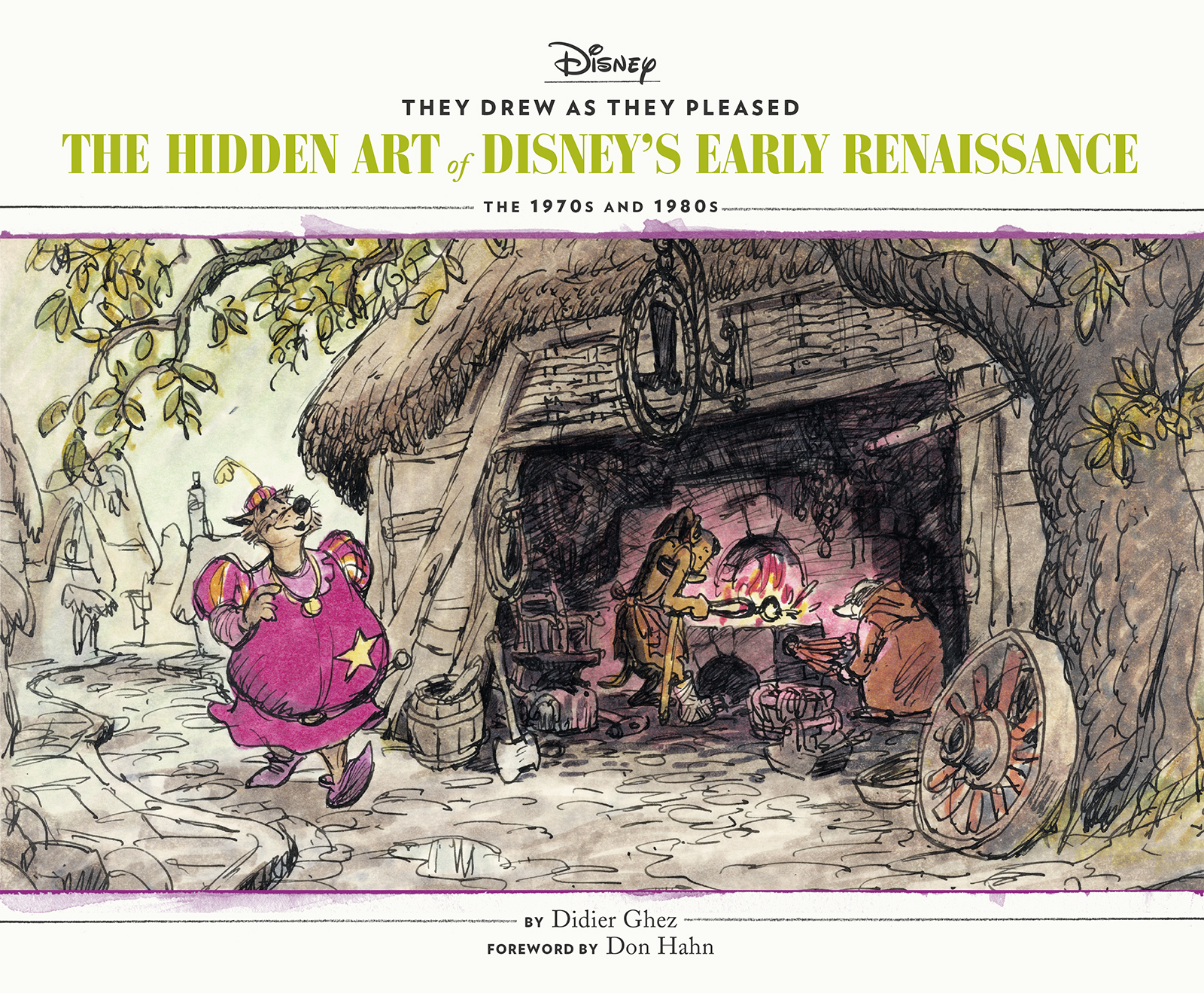

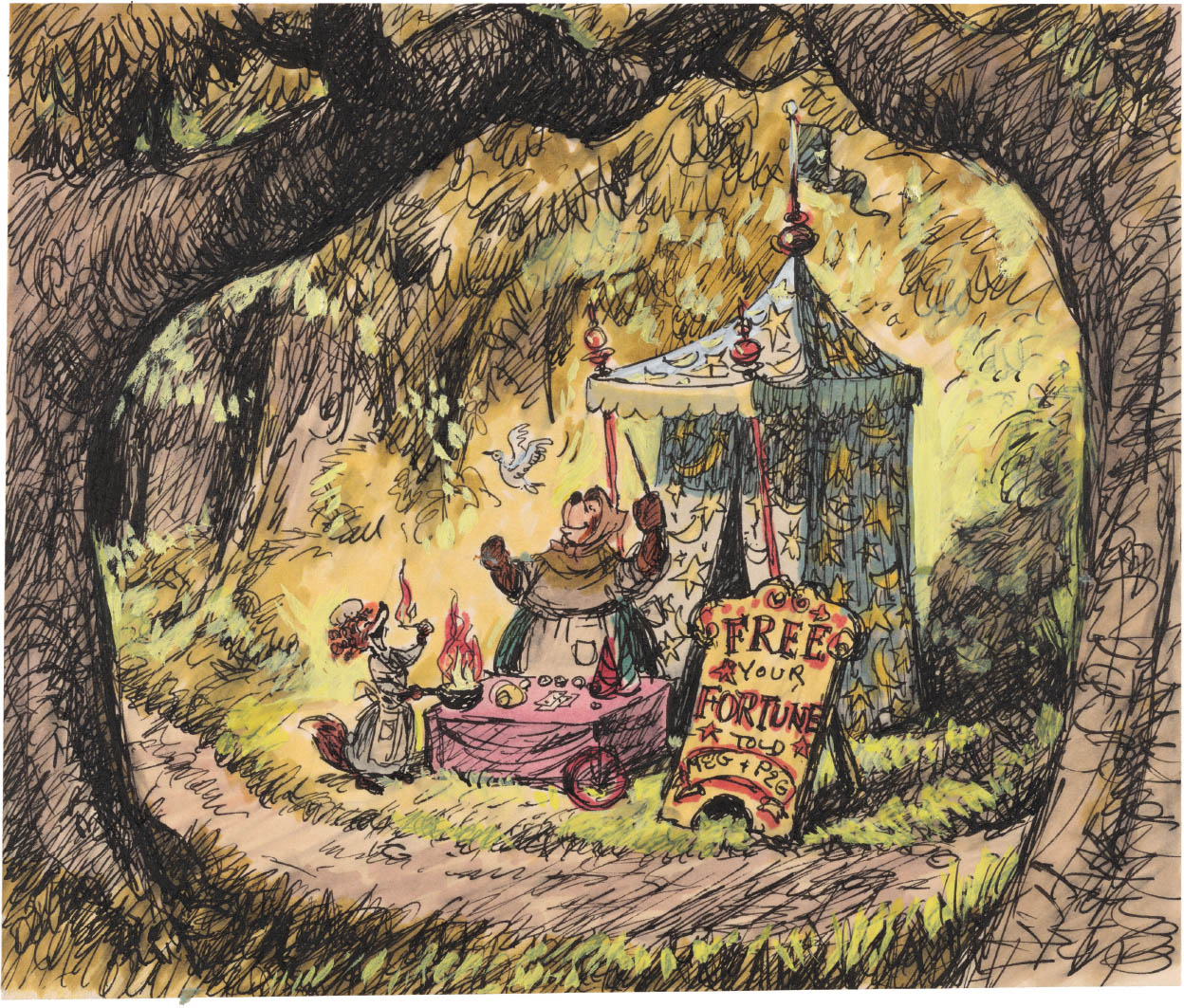

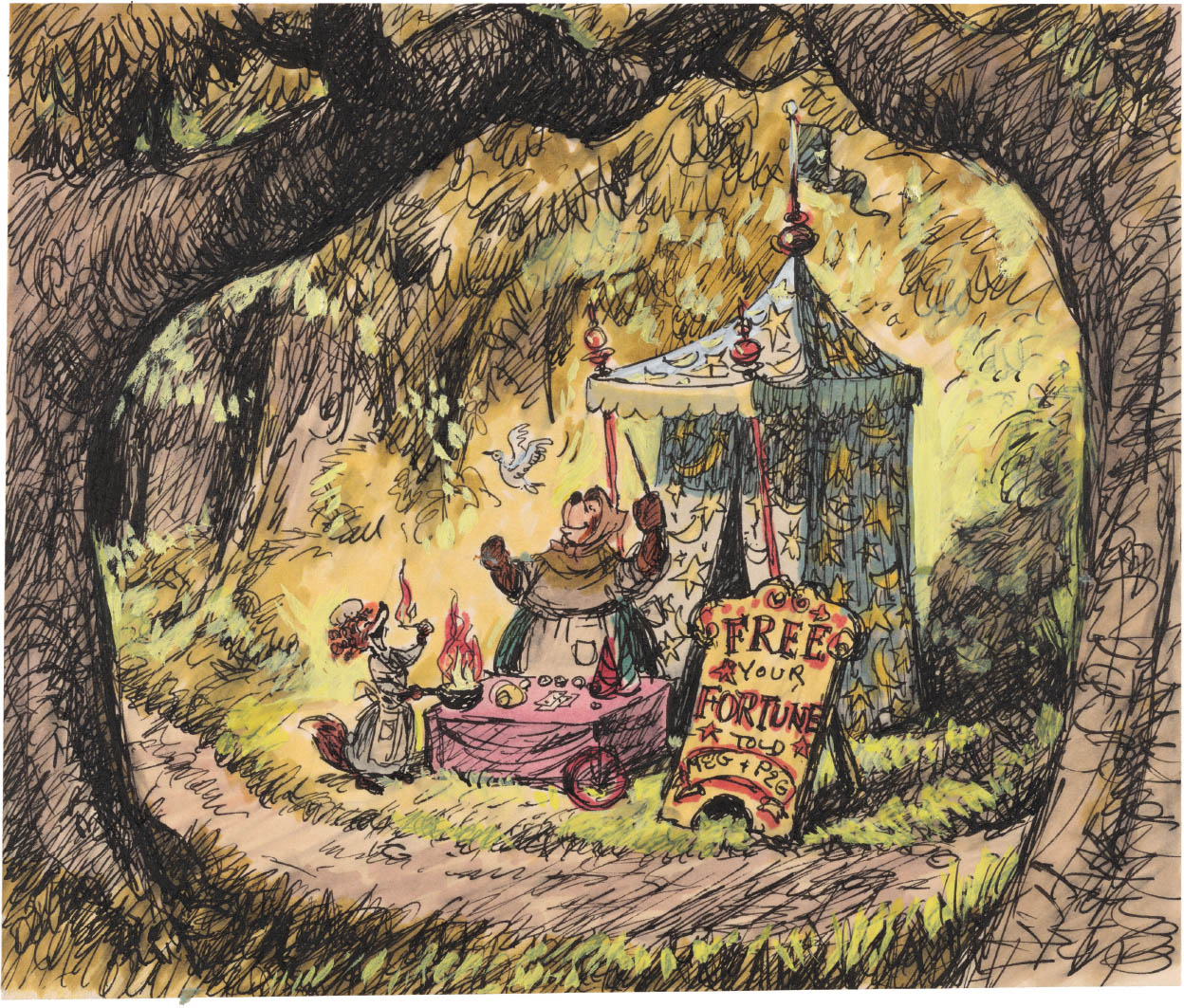

Concept sketch for Robin Hood by Ken Anderson.

To David R. Smith and Michael Barrier, without whose pioneering preservation efforts no one today would be able to write reliably about Disney history

Character studies for Thumper in Bambi by Mel Shaw. Courtesy: Rick Shaw and Melissa Couch-Deranleau.

Copyright 2019 by Disney Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 978-1-4521-7870-7 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-7972-0410-9 (epub, mobi)

Written by Didier Ghez.

Design by Cat Grishaver.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

All of the artwork featured in this volume comes from the Walt Disney Animation Research Library or the Walt Disney Archives, unless specified otherwise in the captions.

CONTENTS

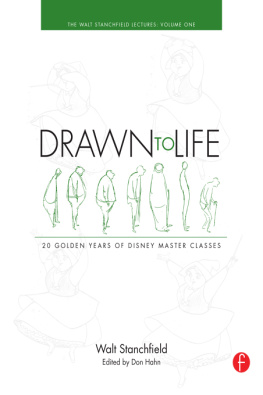

by Don Hahn

Concept sketch for The Aristocats by Ken Anderson. Courtesy: Van Eaton Galleries.

FOREWORD

Great artists go through seasons in their creative lives, sometimes producing brilliant masterworks and other times languishing through hard times of growth and transition. The Disney animators once soared with films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, and Fantasia, but by the 1970s the world had changed and these brilliant artists were struggling. Walt was gone, as were many of the artists who worked on the classics of his era. Back then, a new animated feature premiered once every four years and was met with a warm reception, and yet there was an unspoken understanding that the era of Walt Disney was over. The remaining artists realized that the art of animation would slip away if they didnt reach out to find fresh new ideas and the talent that would reinvigorate the art form.

T HE ANIMATION GROUP WAS LED BY producer/director Woolie Reitherman, who was passionate about keeping the team of veteran Disney animators together to keep the art form alive. There was plenty of reason for hope. Woolie, along with studio head and Walts son-in-law Ron Miller, also knew they had to move confidently and quickly to find new talent, and even more importantly, to develop new film ideas that would attract and keep that talent. The two artists most often tasked with incubating new projects from blank canvases were Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw.

Ken began at Disney in the mid-1930s and soon distinguished himself as a jack of all trades. He was a master draftsman with a gift for creating characters in every shape and size with that magic component that was the hallmark of Disney animation: personality. Mel also started in the 1930s, but after a couple of years he left Disney, and after a stint in the Army he founded his own design firm. When Mel returned to Disney in the 1970s, Woolie leaned on him to generate visionary concept drawings and pastel chalk and watercolor works that would not only flesh out story ideas but also get the crew incredibly excited about a project. Mel was a one-stop shop. He would give you characters, setting, atmosphere, and mood all in one piece and create a vision for a new project years before the film would hit the silver screen.

Character designs for Bianca and Bernard in The Rescuers by Ken Anderson. Courtesy: Wendy Greer.

These two men literally set the stage and designed the characters for every film during this crucial transition period that kept animation alive after Walt and led to a renaissance of the art form.

They were first and foremost storytellers. Both were brilliant draftsmen who could draw in clear, communicative ways, and who lived expansive lives of adventure and travel, with a joie de vivre that showed in their work. Both, along with Reitherman, saw the need to train and inspire new artists, and, by example, they taught a new generation of artists that includes present-day animation visionaries like Brad Bird, Henry Selick, John Musker, Ron Clements, Lisa Keene, and Tim Burton.

I was lucky enough to know and work with Woolie, Ken, Mel, and others like them who generously shared their time and talent with rookies like me. I learned so much about storytelling and the art of animation from them. More importantly, I learned from their ability to approach their work with fresh enthusiasm for ideas and the entertainment possibilities they held. Their attitudes about quality and storytelling were as important as the ideas they put on paper.

Historian Didier Ghez brings these artists back to life in the pages of this book by virtue of his passionate and exhaustive research into their body of work. As you enjoy this volume of They Drew as They Pleased, remember that these artists created work that has entertained generations and even changed popular culture, an accomplishment that only a handful of artists can claim. As you will see in their work, they were inspiring and dynamic personalities who reveled in bringing their creative ideas to life in a way that excited everyone from Walt Disney to their fellow artists, to audiences everywhere.

DON HAHN

PRODUCER/DIRECTOR

PREFACE

The 1970s were a time of upheaval in the United States and an uneasy time for the artists at the Disney studio. Walt had passed away in 1966. No longer could they rely on him to lead the studio and shape its vision. They had to reinvent themselves, picture-by-picture, project-by-project, producing a rebirth of sorts. A renaissance.

I WAS BORN IN 1973, the year Robin Hood was released, and have always had a soft spot for the animated features of this decade, from The Aristocats (1970) to The Rescuers (1977). This might also explain why, thirty years ago, the first two Disney concept artists who caught my attention were Ken Anderson and Mel Shawmen who largely defined the style of Disneys cartoons in the 1970s and early 1980s. When I discovered Ken Andersons character designs for Robin Hood in the first edition of the book The Art of Walt Disney

Next page