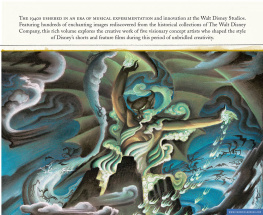

Encounters with the mermaids of Never Land. Courtesy: The Walt Disney Family Museum.

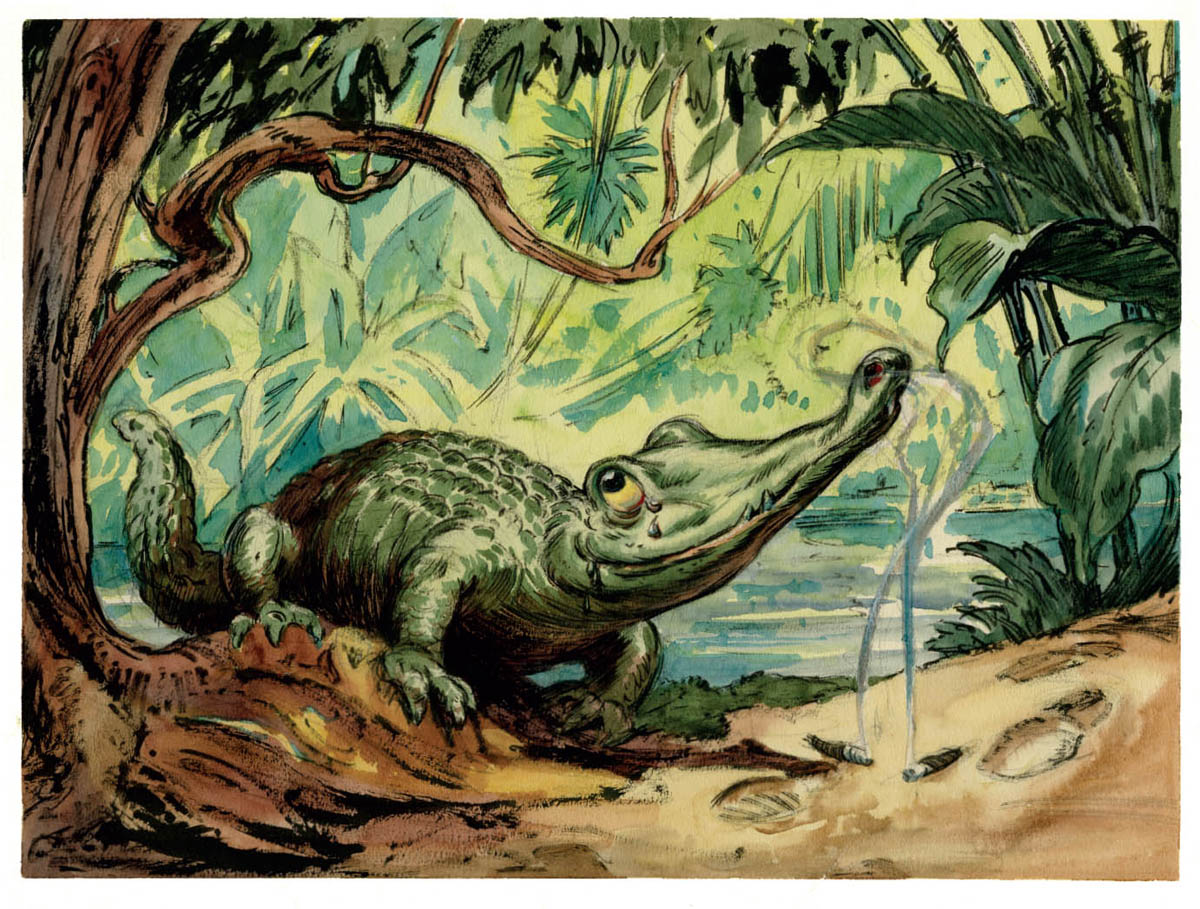

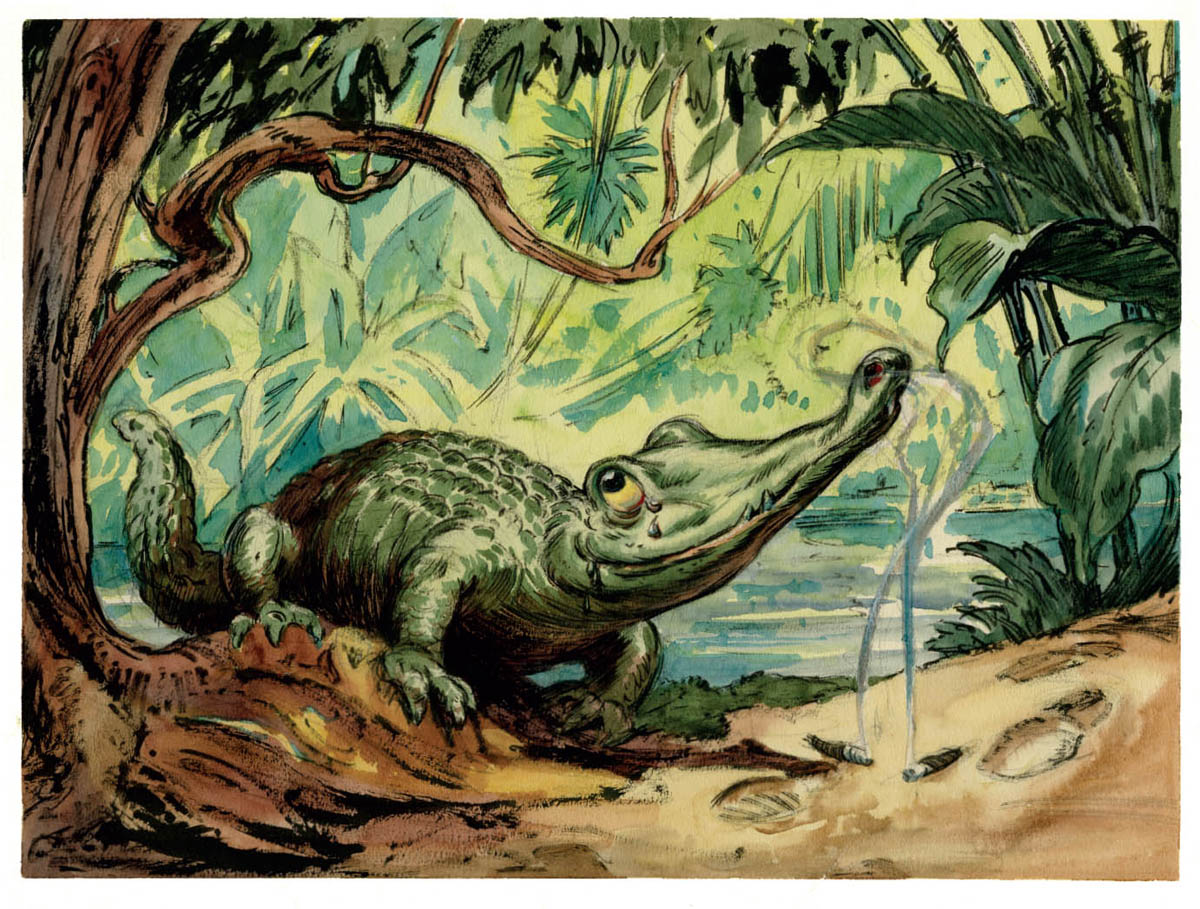

The crocodile from Peter Pan by David Hall.

To my brother Fabien,

who keeps dealing with my crazy Disney requests,

even in China.

Character studies by Walt Scott for the abandoned bug orchestra sequence created for Fantasia.

Character studies by Walt Scott for the abandoned bug orchestra sequence created for Fantasia.

Copyright 2016 by Disney Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-3744-5 (hc)

ISBN: 978-1-4521-5861-7 (epub, mobi)

Written by Didier Ghez

Design by Cat Grishaver

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

All the pieces of artwork featured in this volume come from the Walt Disney Animation Research Library, unless specified otherwise in the captions.

FOREWORD

It has been highly satisfying to peruse Didier Ghezs latest volume in his ongoing They Drew as They Pleased series because it combines two of my passions: classic Disney animation and the detective story.

It is fairly obvious , of course, that this volume centers on animation and art produced during Disneys musical years. But this book is also a detective story, one set in the period and place of so many of my favorite noir fictions: 1930s and 40s Los Angeles. Didier, like a shamus of old, has gathered and unearthed information about mysterious characters who toiled in these mean Southern Californian streets: visual development artists who made significant and important contributions to the Disney films of this classic period, yet have somehow remained shadowy figures about whom relatively little has been known or written.

These artists, all gone from this world now, come alive in these pages, not only in the exceptional drawings and paintings displayed herein, but also in their correspondence, in recollections by colleagues, in memories shared by loving family members, and, in some cases, the artists words themselves, gleaned from past interviews.

The 1940s were a particularly challenging time at the Disney Studio. Despite the brilliance of the films produced then, World War IIs effect was sharply felt as overseas markets disappeared and the box office shrank. The Disney strike was devastating, and the layoffs that ensued, prompted by both the strike and the declining revenues, had, in some cases, punishing effects on the livelihoods of the artists who toiled there. Didiers narrative gives a real sense of the atmosphere of uncertainty under which many of the artists in this book attempted to produce carefree drawings.

This tome also sheds long overdue light on creative women like Retta Scott and Sylvia Holland who helped shape the films of this period with their unique and powerful visions.

Most touching and personal to me are Didiers glorious sampling of art and discussion of the roller-coaster Disney career of the brilliant Danish illustrator Kay Nielsen. This volume reproduces not only Nielsens powerful designs for the Night on Bald Mountain sequence in Fantasia, but also other no less stunning drawings for projects that never came to be, like the proposed new Fantasia sequence, The Ride of the Valkyries, and a 1940s version of Hans Christian Andersens The Little Mermaid.

Vance Gerry, one of Disneys great storymen and a mentor of mine in my early Disney career, first brought Kays drawings to my attention when Ron Clements and I were making The Little Mermaid. We had never known such work was done or that the Studio had ever considered bringing Andersens tale to life. We found these Nielsen masterpieces in the Disney Morgue, the repository of art from past projects, and had them displayed on storyboards in our rooms as we worked on Mermaid. They certainly inspired us, particularly Kays epic drawings of the storm, and they inspired drooling from visitors to our offices as well, like visionary director Terry Gilliam. He was weighing doing a live-action feature with Disney at the time, and I still remember his wide-eyed look as he ogled Kays drawings, comparing them to the legendary film designer Anton Grot, and him asking us with a wicked grin, Are they gonna let you do it like this?

Friend Owl from Bambi by Retta Scott. Courtesy: David Tosh/Heritage Auctions.

Kay Nielsens story, as recounted here by Didier, is itself Andersen-esque. The fragility and beauty of Kays incomparable drawings, and the quiet demeanor that concealed the passionate artist within, is juxtaposed with the real-world issues of salaries, exciting projects developed but never realized, and a life that ended sadly, in both obscurity and poverty. It is truly touching, and like most of the great Andersen tales, bittersweet. But this book brings a happier ending as Didier shares and celebrates Kays graphic genius with a wider public.

So enjoy, lucky reader, as did I, not only these drawings, but all the fruits of Didier Ghezs inspired and hard-won detective work: his glimpse into the lives and artistry of people who touched people they never saw, who shared their passion with audiences who never knew their names, and whose work will continue to move generations for lifetimes to come.

JOHN MUSKER

PREFACE

The late 1930s and early 1940s were a dark time in the world: Europe was at war and the long shadow of the Great Depression still darkened economic prospects. But at the Disney Studio creativity flourished.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was a triumph. More artists flocked to the Mouse House in the late 30s than ever before or since, and more projects were developed by the Story Department during that era than at any other point in the Studios history.

The artists came from the four corners of the United States, but also from England, France, Denmark, and even Ecuador. They brought their various cultures, backgrounds, and knowledge to Disney, which enriched the Studios creative culture and widened the scope of Walt Disneys vision.

Walt selected the most visually talented among them to become concept artists. Their wild imaginations sparked the creativity of fellow artists, influencing character designs, settings, and story ideas. Had this boundless creativity been projected onto the screen, however, it would have resulted in storytelling and design chaos. Walt brought order and structure; he was the great visionary who orchestrated visual coherence and gave narrative power to the whole.

Next page