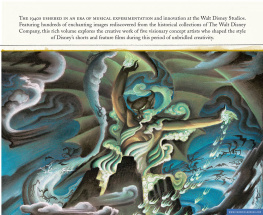

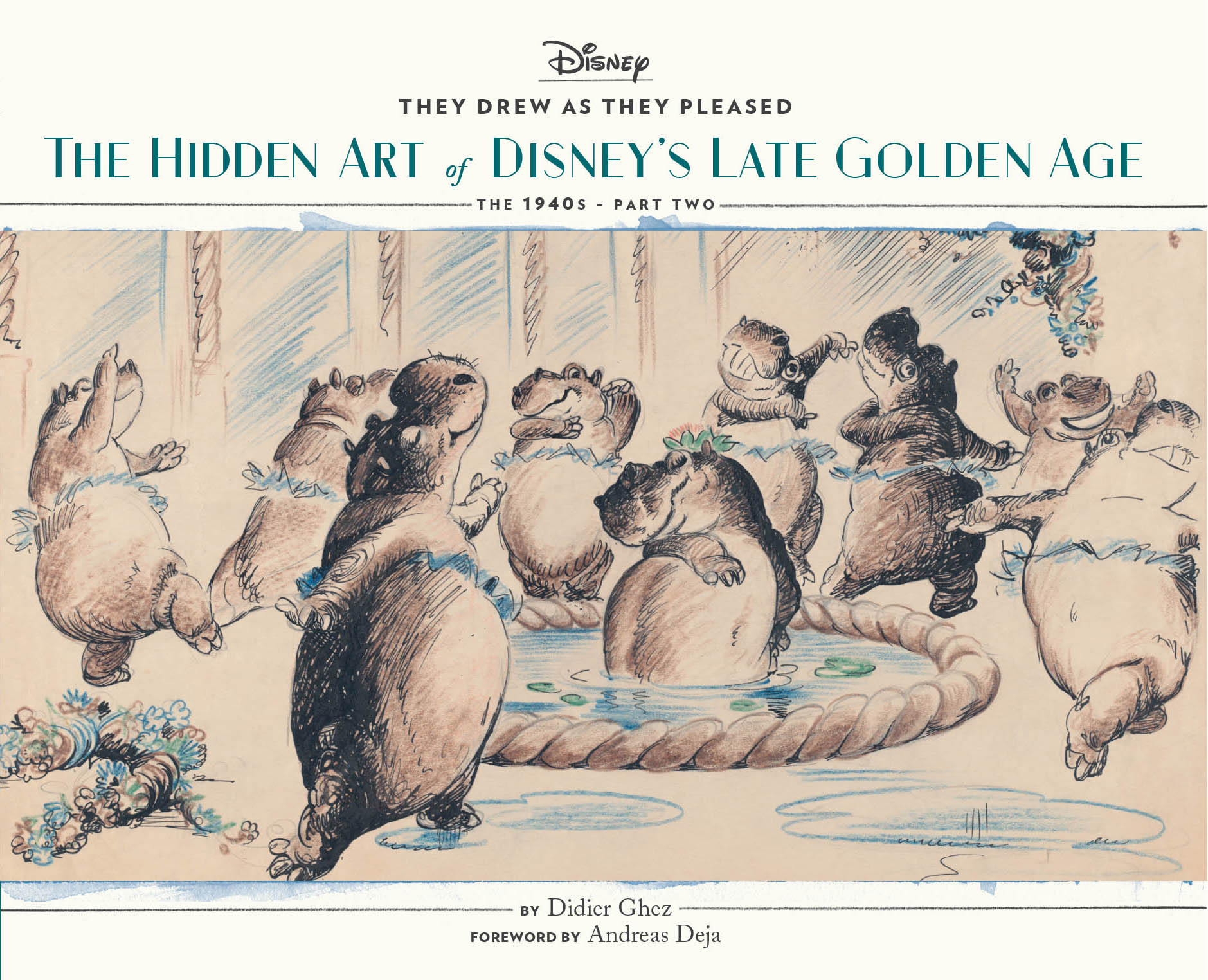

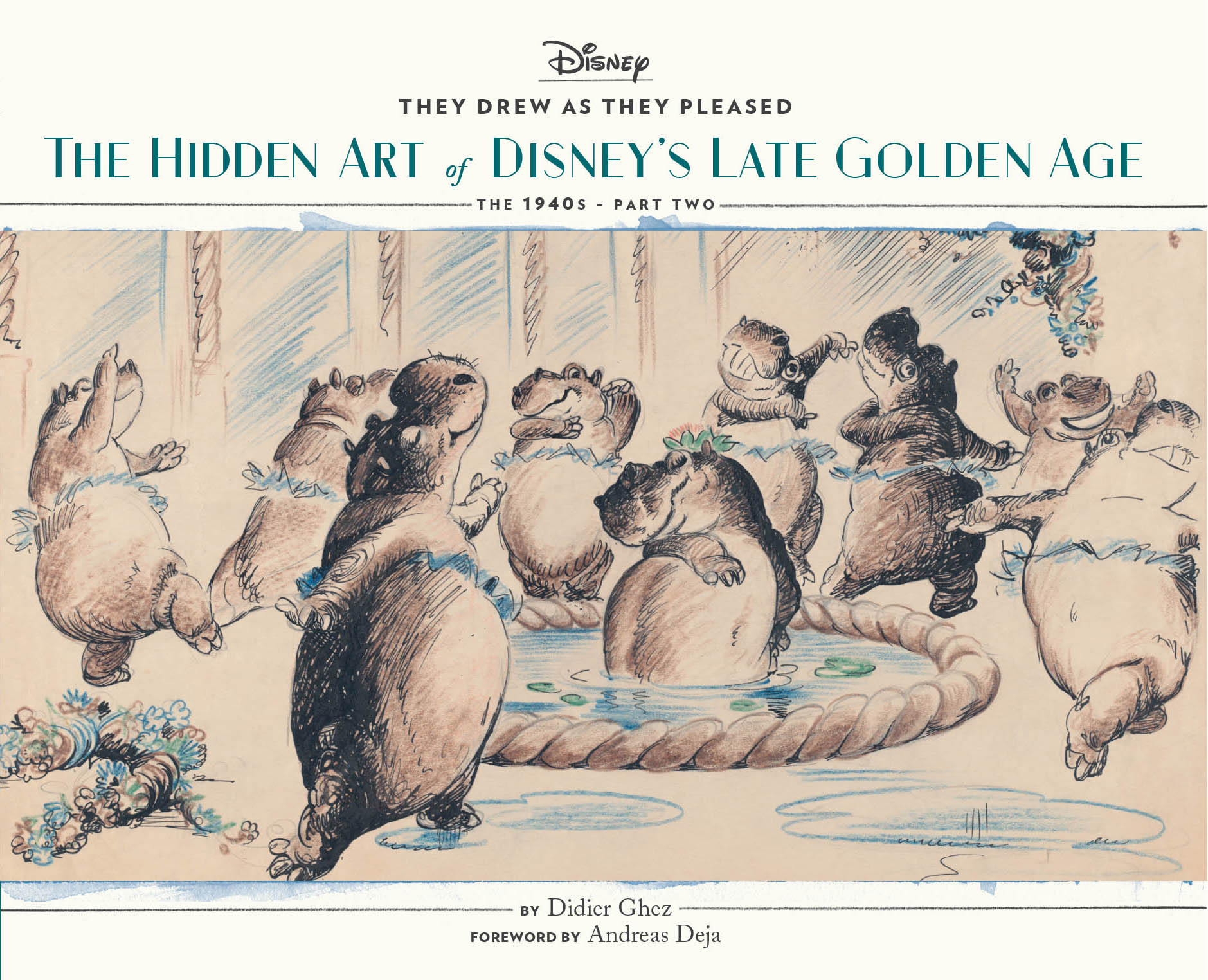

Concept painting for The Dance of the Hours featuring Hyacinth Hippo and Ben Ali Gator. Courtesy: Hakes Americana & Collectibles.

Copyright 2017 by Disney Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form

without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-5193-9 (hc)

ISBN: 978-1-4521-6407-6 (epub, mobi)

Written by Didier Ghez

Design by Cat Grishaver

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Character design for a Lost Boy in Peter Pan. Courtesy: Heritage Auctions.

All of the artwork featured in this volume comes from the Walt Disney Animation Research Library or the Walt Disney Archives, unless specified otherwise in the captions.

To my wife, Rita Holanda Ghez:

I wished upon a star and met the fairest one of all.

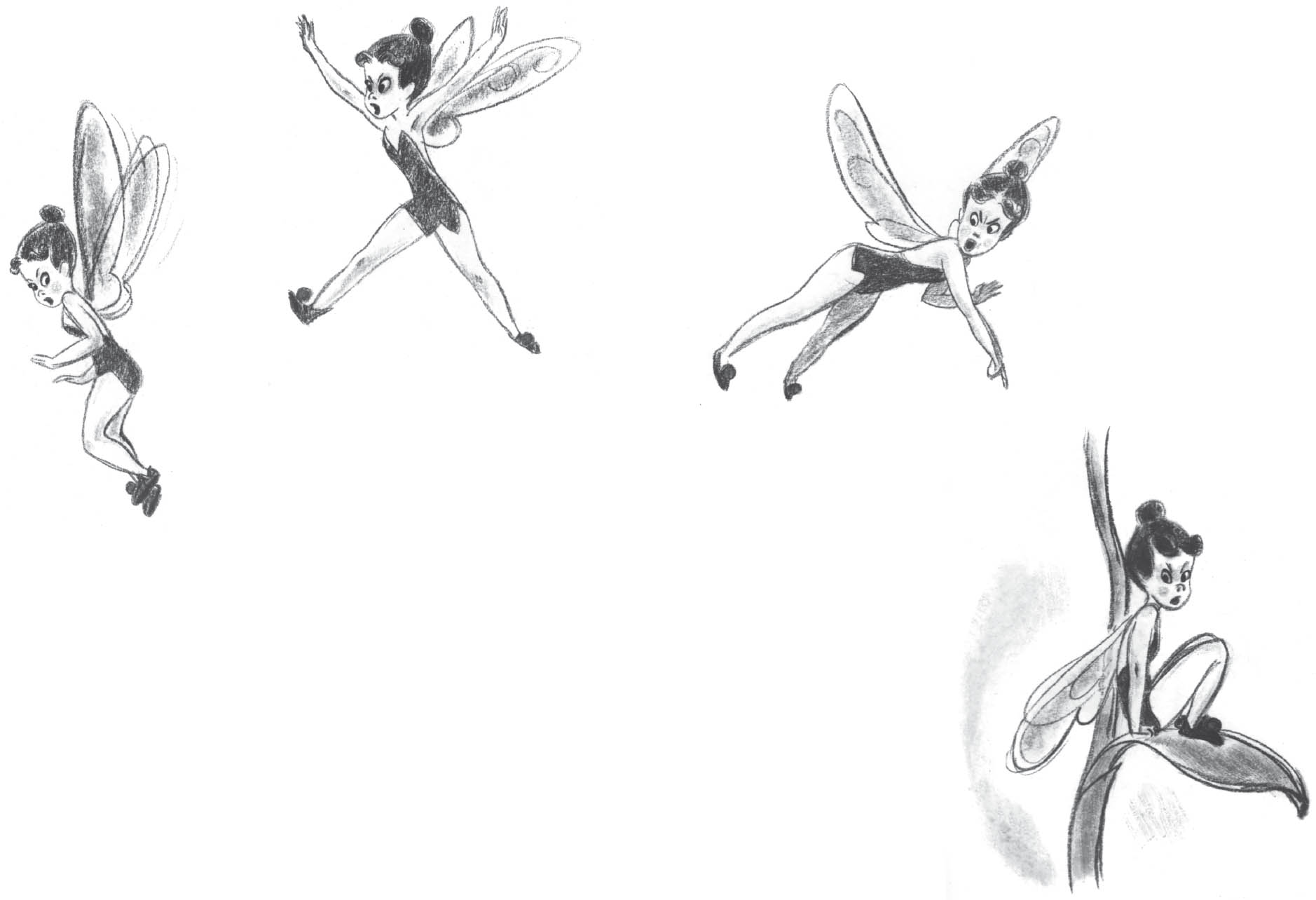

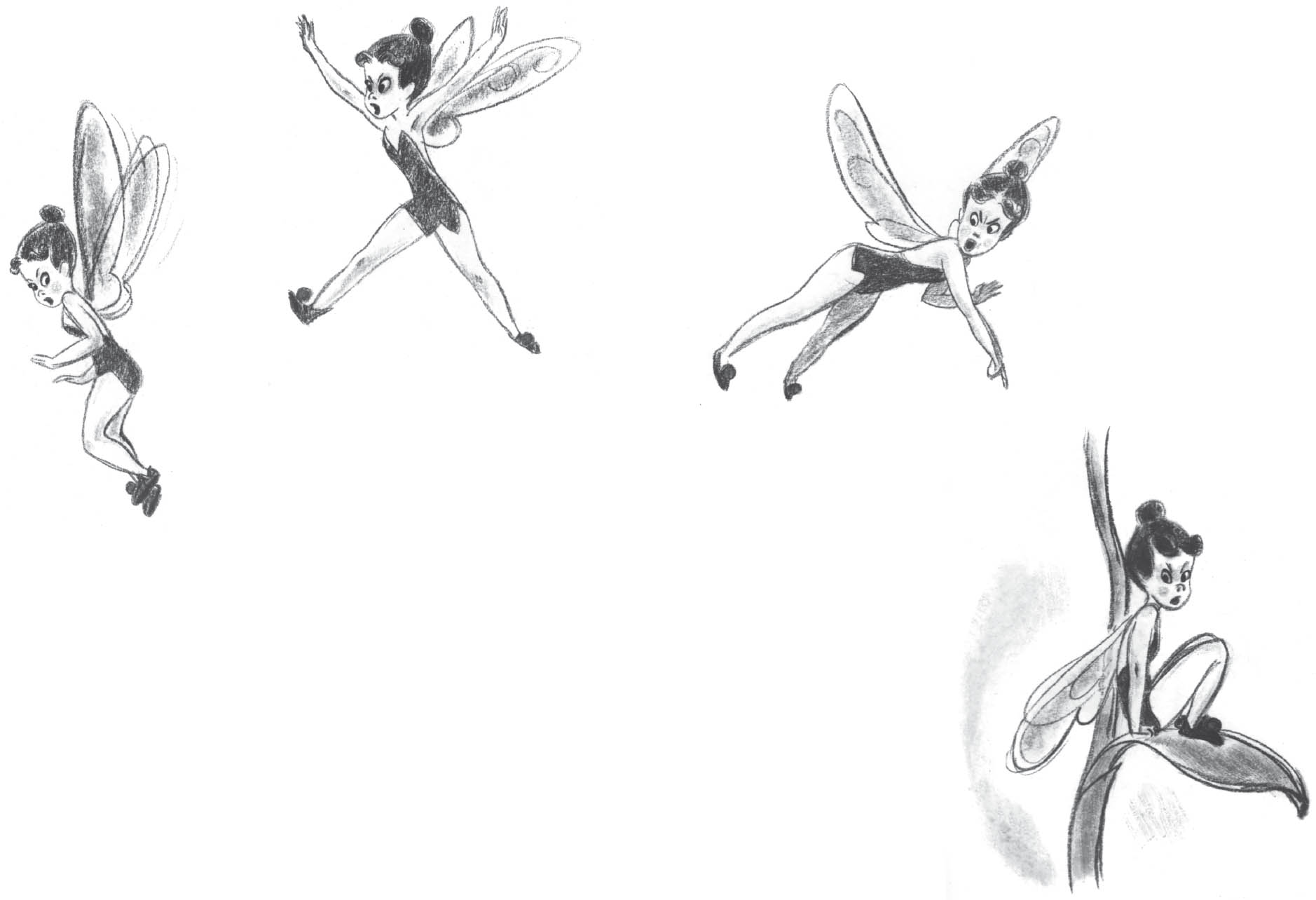

Tinker Bell from an early model sheet for Peter Pan by Jack Miller.

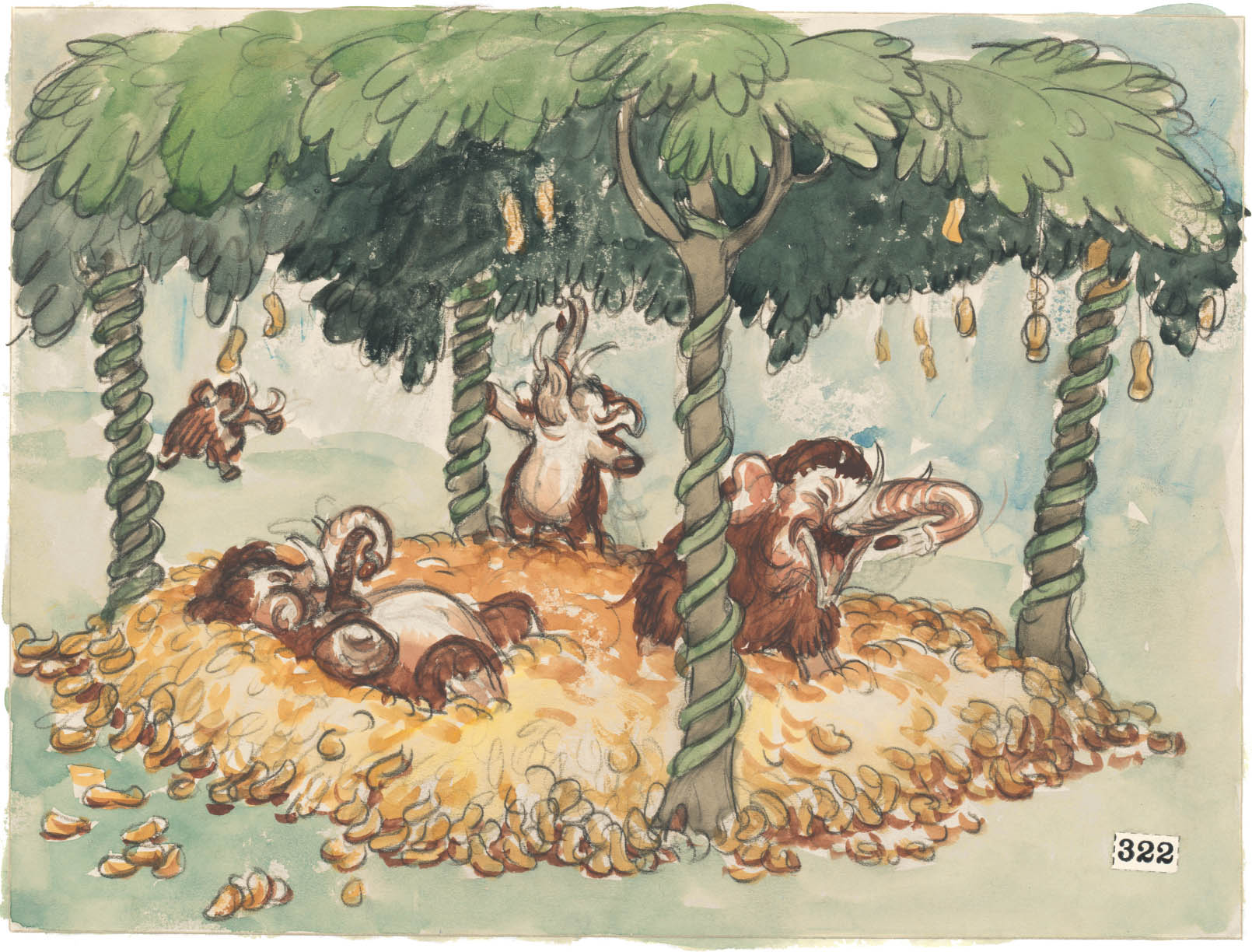

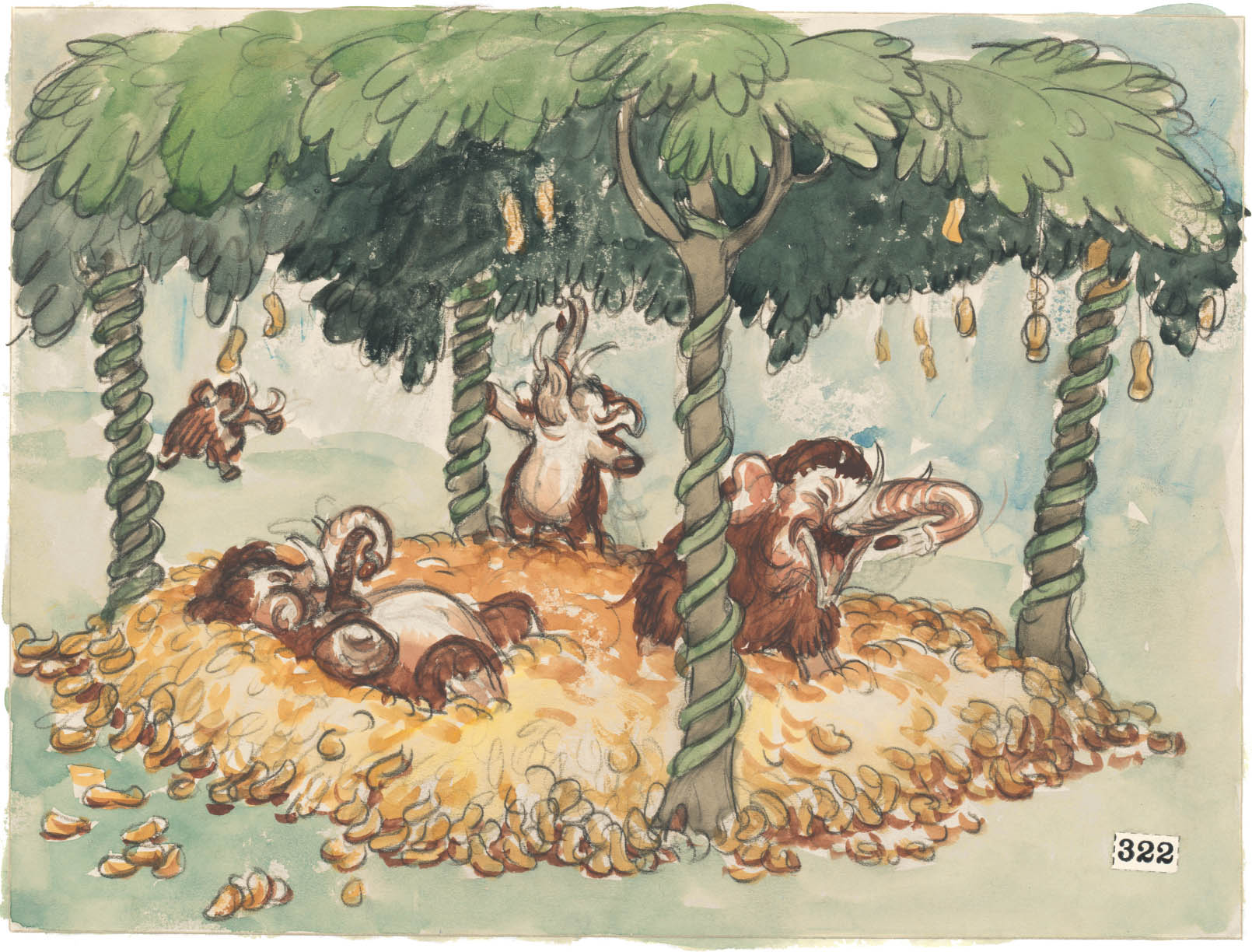

Storyboard sketch by James Bodrero. The elaborate Dumbo sequence The Mouses Tale did not make it to the screen.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

During the golden age of animation, Walt Disney asked for the formation of an in-house branch that would be responsible for all sorts of preparatory artwork in support of his animated features as well as short films.

Some of Disneys animators felt a sense of jealousy toward other studio artists who were part of a group working in the newly created Character Model Department. While the animators main drawing tool was only a pencil, members of the Character Model Department were free to use any artistic medium they desired, from pastels to watercolors, from pen and ink to the creation of three-dimensional character sculptures. Self-expression was encouraged, as is evident in the pages of Didier Ghezs third beautiful volume of They Drew as They Pleased. Individual personal styles emerge with each chapter.

Eduardo Sol Franco created rich Dali-esque watercolors for an unproduced Don Quixote project. Johnny Walbridges surreal sense of humor comes through in his experimental designs as well as actual story work involving the clowns from Dumbo. Jack Miller had an extraordinary feel for clear staging, as is evident in his masterful story drawings for Baby Weems. Campbell Grant invented whimsical gag drawings for some of Snow Whites Dwarfs and model sheets featuring lively poses of ostrich dancers, inspired by Edgar Degass work. James Bodreros expertise in depicting horses led to assignments for Fantasias Pastoral sequence, which included groups of centaurs. He also provided unique character development for a screwy horse in El Gaucho Goofy. Martin Provensens graphic range is evident in his cheerful sketches of circus animals for Dumbo and in the influence of Russian folklore illustration for Peter and the Wolf.

Within the confinements of an increasingly specialized animation studio, these artists expressed themselves freely and individually. The search for new looks and fresh designs was paramount during the 1930s and 40s, as long as the art represented the overall vision for the films story.

Yet animators like Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston used to complain about the fact that the work done by the Character Model Department couldnt be applied to their character animation. The animators craft dealt with lines and shapes, and for the most part the characters final look on film represented that aesthetic. Nuanced shading or bold sketchy lines were almost impossible to replicate on painted cels. And even though films like Pinocchio and Fantasia included various dry- and airbrush techniques, these procedures occasionally resulted in unintentional flickering when projected onto the screen. They were also very costly.

Sketches from an early model sheet from Peter Pan by Jack Miller.

Thankfully, Disney supported the idea of thinking outside of the box, particularly during the preliminary stages of production. A forceful pastel sketch or a soft watercolor painting just might trigger a new way of looking at the productions design and characters.

During my tenure at Disney I had the good fortune to work and interact with the former head of the Character Model Department, Joe Grant, who had returned to the studio after several decades of absence. At that time, Joe contributed unique visual ideas for stories and characters. He worked on such films as Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King. I once asked him how he would compare his early years at Disney to the current times. His answer: Oh, it was the same in many ways. We too had politics, disagreements, and frustrations. But we drew better then.

So let this latest entry in Didier Ghezs unique book series serve as a reminder of the high standard that Walt Disney and his artists had for creating visual worlds within the animated medium.

ANDREAS DEJA

THE STORYTELLERS

During the anxious month of December 1935, while the studio muscled toward Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Walt Disney summarized in two sentences what he then saw as the primary challenge in producing both popular and artistic films for a wide audience: Without good stories, we cannot make good pictures. Without well-prepared stories, we cannot make the pictures efficiently.

A little over a year later, in early 1937, with less than twelve months before the release of his first animated feature, Walt intensified his focus on this seminal issue. His story team was strong and he was a genius when it came to building powerful and entertaining stories. But this was not enough. To ensure its storytelling future, the studio needed to locate or to develop more good tales and endearing characters from scratch. To achieve this unique goal, Walt decided to establish two new departments in his quickly growing companythe Story Research Department and the Character Model Department.

Next page