Perditus Liber Presents

the rare

OCLC: 574446528

book

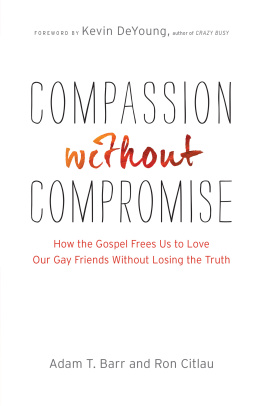

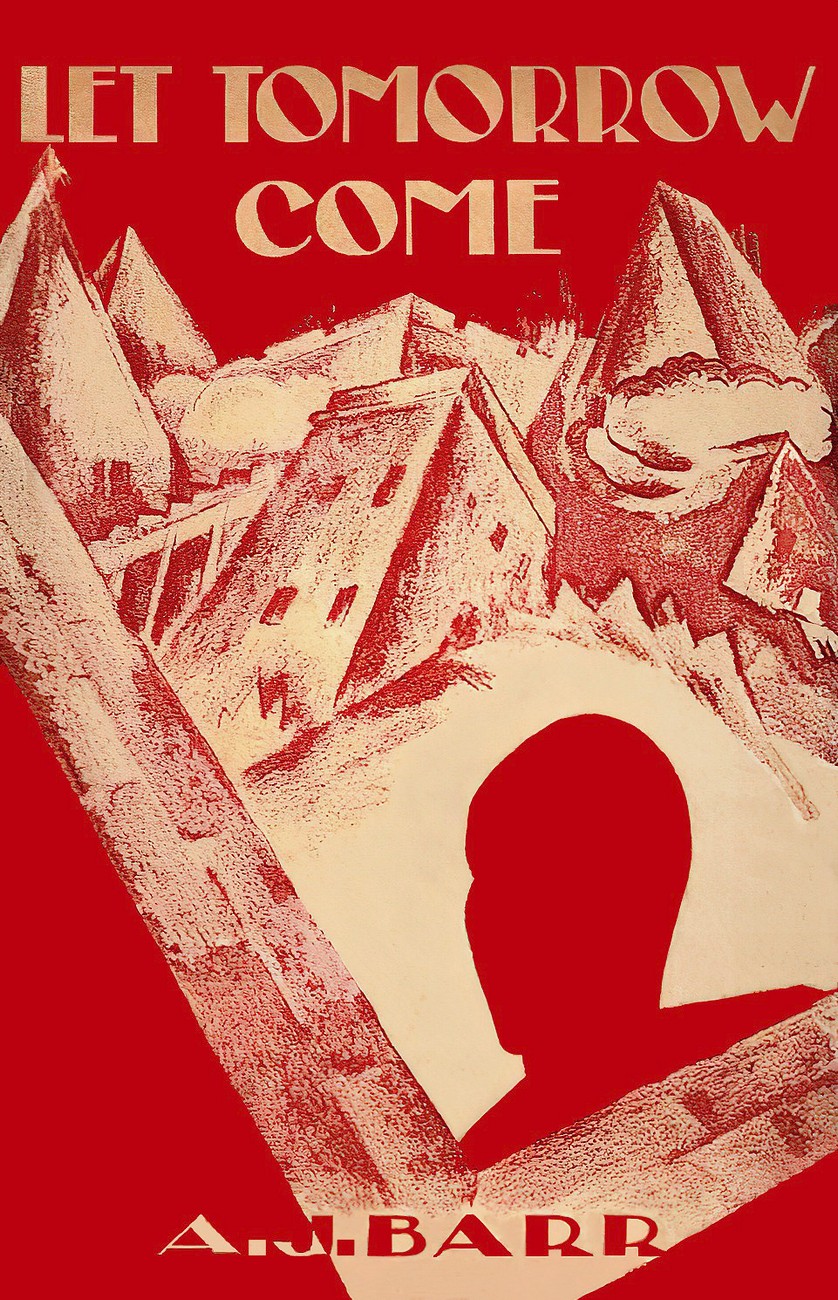

Let Tomorrow Come

By

Albert J. Barr

Published 1929

LET TOMORROW COME

Copyright, 1929

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY, INC

First Edition

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OP AMERICA

FOR THE PUBLISHERS BY THE VAN REES PRESS

CONTENTS

JAILHOUSE

Ah laid in de jailhouse

Face to de wall:

A sweet dirty woman

Was de cause of it all

I

JAILHOUSE

H ERE, by God, we are! Made it at last! We care and we dont. Most men who arrive here have in varying degree expected to arrive. All save the snowy have at least been aware of liability. We care, for that, whether those who are to meet us will accept us. The dog and the name. Tell no man he is bad and watch for goodness to shine out from him. Slam him in jail he will battle for release. But winning, he will tell his affairs twice as black as they were. The lowliest doormat-thief will name himself a dino of surpassing ability, but give him half an opportunity.

And the women. Ho, ho, the women! Any two-bit tart will be a madame inside ten minutes, can you listen to her that long. She will tell you how none less than the mayor, and perhaps even the thickest pillar in the ministry,

comes to her alone, prefers her among all the sisters.

Cut out that God damned noise or Ill shove you in the hole. They wont hear you in there. The jailer is so telling us who, precisely, runs the dump.

He comes over. Gwan in there and louse up. And if you slop up the floor, then clean it up again. Remember.

No matter where you may have come from, the flop house or the club, here you are suspected of harboring flesh-nipping chattel, and must slay them. If you are a man. If you are a woman you are accorded the delicacy of a fumigation.

In we go. We strip in an odor of excrement from under the great rotary cage, two decks high, and shove our clothes into a tub. After soaping them we turn live steam into the tub through a hose. The tub jumps on the steel floor, making a rumbling clatter. If the heat did not kill him, the hardiest louse would die of despair at the noise. A voice from far on the other side of the rotary: Must a been heavyweight

skippin bees you boys brung in here. Youll burn up your damn clothes if you dont stop.

In the tub the water whoops and bawls, tortured by the steam. A clinging, stinking vapor seeps through the place, enwrapping our chilling nakedness. Outside the blurred windows the light is wilting. The jailer comes in to us. All right, you aint killin mules. Thems lice. Wring em out and come on over here and Ill show you where you cell. You can wrap a blanket on you and hang that stuff on the steam pipes. Eat your beans while its dryin. There aint no coffee. Too late. And pipe down when nine oclock comes, or its the hole.

We follow, our flesh stuttering with chill. A lamp burns in the three-story-high ceiling, dimming the place with shadow rather than lighting it. Few cell lamps have been turned on. We have come upon the thinking time of most of the inmates. One does not think. Hey, fellers, he shouts down at us from a high cell, where the hells your pants? Shame on you. Youre hangin out a mile. He goes off into a great cackle at his joke.

The jailer unbuttons a heavy door and we pass through. Wanta cell together? All right, Jack, grab your stuff and go on over with Mosely. Yes you will.

Back at the end of the corridor in front of the five cells of the deck a mucous-colored face floats above the open toilet. Our beans are cooling on a shelf just inside the door through which we entered. Jack sullenly hauls his mattress and blankets out and away. We will not be too well set with Jack.

All these birds is federals too, the jailer informs us at parting, so you can have a lot of fun framin with em about what youll do to the screws at Leavenworth. But dont do nobodys time but your own in here. That ways best.

We take the pans to our cell. Someone calls to us from down the row: If you find a bean with legs on it thats a cockroach.

After the pans have been emptied a dark little cripple comes in casually and sits on one of the bunks. Made you boil up, did he? Damned fool. No use. They grow bigger in here than

anywhere youve been, even if its a lot of places. Dont mind him. He aint bad. Just noisy.

This is not the visitors purpose. He knows we will learn the entomology of our home soon enough. One of his eyes is off center outward. Behind the eyes is a neat, if limited, intelligence. He is about fifty. In his manner, no matter its seeming of ease, is a tense aloofness, the hiding of self behind the barrier of ineffaceable impressions that he may read us the better. He has had hard experience of hard men. His presence in the cell is not even an earnest of acceptance. We are birds who, his memories tell him, might make him as soon as any other a feather in our nest. Men who make the jailhouse know that each of their fellows lives on suspicion and deceit, hatred and offhand treachery, black craving and the easiest way to fulfillment.

Whats the rap? he asks, striving for unconcern. The rap is the man, and the cripple knows it. Some men love the theater; some not. Some beans; some not. Likes are signs. A dimes worth of postage stamps, a million dollar consignment of hop or a nitwit tommy taken ten miles interstate for a bed each rates you a

bunk in the federal cell-block. The rap is the label that shows you big-time or a tanker.

We tell the cripple enough to let him fix us, and wait the returns. He smokes, and goes out. As we make up our bunks we hear him reporting, still with the easy manner. There are six besides himself and us in the ten-bunk tier. Jack was doing it alone until we arrived. After half an hour the cripple returns to invite us into a six-handed poker game. We accept. No aristocrats in this gang. The game is for nickels and dimes and close to the belly.

Sundown let tomorrow come. Sundown let tomorrow come. Sundown let tomorrow come. Sundown let tomorrow come. Sundown let tomorrow come. Sundown let tomorrow come. Over and over and over, again and again and again it goes, until finally we become conscious of it to the exclusion of all other sounds. The phrase is whined in a broken-reed voice that has an ignorant quality. The cripple is all insane nerves. As the lunatic iteration continues he fumbles his deals, misreads

his cards, and finally throws them up. He leans back against the steel wall of the cell, slowly, terribly restrained, taut as a shriek with the effort at control. Gradually he steadies. The worst is past for the minute.

Sundown let tomorrow come. Sundown let tomorrow come. Sundown let tomorrow come.

The cripple says very slowly, very deliberately, I think Ill kill him tomorrow. Ill make him a sundown. Hes got me. I cant stand it any longer. Im going nuts and I know it. I wasnt ever like this before. Hes got four more months to do and Ive got five. Ill never make it. Ill knock him off.

He is too sincere. None of us dares urge against what he intends.

Sundown let tomorrow come. Sundown let tomorrow come. The cripple turns his head until he faces to a hair the direction of the torture. His eyes pass a shade dull. He is killing now, detailing in his mind each feel and motion of the act. Sundown let tomorrow come. Sundown