Contents

Page List

Guide

Contents

The Birds

AFRICA

EURASIA

NORTH AMERICA

SOUTH AND CENTRAL AMERICA

SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA

AUSTRALASIA

OCEANS AND ISLANDS

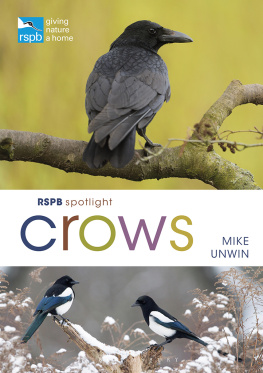

Its 7.45 am and already birds have stamped themselves on my day: over breakfast, the chime of a great tit and machine-gun rattle of magpies from the garden; now, upstairs at my desk, the mewling of herring gulls drifting past my window. My tiny urban patch is hardly a bird reserve and yet by the end of an average working day, including a lunchtime stroll around the park, I will generally have seen or heard some 25 species. Add to that the profusion of avian imagery that I am bound to encounter from book spines to tattoos and its clear that there is no escaping birds.

This is hardly surprising, given how numerous birds are. Taxonomists continue to debate the precise number of species, with new DNA-based classification systems overturning traditional morphological ones, but a total somewhere north of 11,000 is now widely accepted. Compared with some 6,400 species of mammal and 10,000 reptiles, this makes Aves probably the most diverse of all vertebrate classes.

Of course, these species are not evenly distributed. The richest habitat for birds is tropical forest, which explains why six of the worlds top ten bird-rich nations are in northern South America, with Colombia (home to over 1,950 species) being number one. However, there is nowhere that does not have its own avifauna. The extraordinary versatility of birds as a group has enabled them to conquer the most hostile landscapes, from deserts and mountains to ice-caps and the open ocean. Their ability to fly leaves no corner of the planet out of reach and allows them to escape harsh winters or seasonal food shortages by simply migrating to pastures new.

But its not just about numbers. While most mammals are small and nocturnal, and most reptiles hidden away under rocks or leaf litter, birds are noisy, colourful and conspicuously present in every sphere of our daily lives. As a child growing up in a UK town, my imagination may have been teased by pythons and polar bears in distant lands, but it was the local birdlife that I could actually see, and thus the much more real possibility of glimpsing my first kingfisher or barn owl that lured me out into nature and inspired a lifetime passion for the natural world.

The in-your-face ubiquity of birds may explain why they have generated more research and inspired more art over the centuries than any other faunal group. In science, they have been the gateway to our understanding of such fundamental concepts as evolution (think Darwins finches). In culture, they have spawned endless music, art and literature, and become emblematic of everything from military might to spiritual transcendence. From Noahs dove to the sacred quetzal of the Aztecs, every society has held up birds of one kind or another as mirrors to its own values and beliefs.

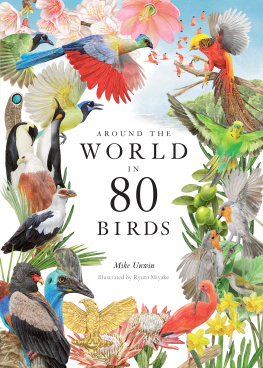

This book tells the stories of 80 bird species, each representing a country or territory where it finds a particular significance. The selection aims to showcase the diversity of the avian world. It includes household favourites, ocean wanderers, formidable raptors and tropical beauties. But rather than being an identification guide or coffee-table gallery, this book is more concerned with what the birds mean to us. Each species is described not only in terms of its natural history but also in the context of its relationship with humankind, whether cultural, historical or scientific.

Whittling down my selection to 80 species was a thorny challenge. I could as easily have chosen 80 others and you may be puzzled or disappointed that such perennial favourites as peregrine falcon and peacock didnt make the final cut, or that I failed to accommodate a single heron or woodpecker. But my dilemma, I hope, simply emphasizes the breadth of riches on offer.

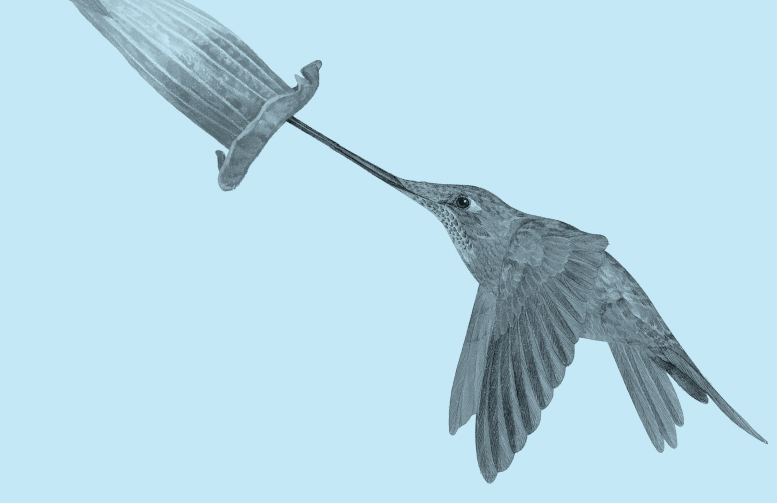

Across the list, it is clear that birds grab our interest and attention through certain consistent factors. First, of course, is basic visual impact. For the Malayan peacock-pheasant, it is simply exquisite plumage that wows us. Many birds flaunt their finery in dramatic displays: the Andean cock-of-the-rock and the superb bird-of-paradise leap out, literally, in this respect. And we are often grabbed as much by the bizarre as the beautiful: take the inflated air sacs of a displaying greater sage grouse or the preposterous lance of a sword-billed hummingbird.

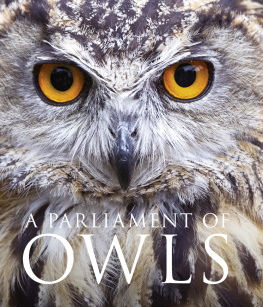

But the appeal isnt only visual. Birds also have voices, which excite both our ears and our imaginations, encouraging us to attribute to them meanings of our own. The complex melody of a common nightingale has become imbued with lyrical romance while the hoarse kronk of a raven is associated with death. And nothing can evoke place quite like the call of a bird, whether the Canadian wilderness embodied in the quavering wail of a common loon or the dusty Australian outback captured in the cackle of a kookaburra.

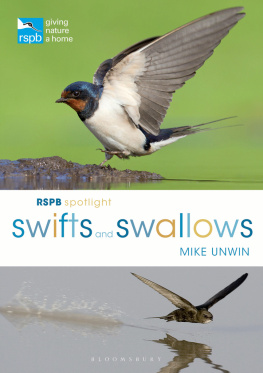

The extraordinary things birds do also inspire us. We applaud the skill of a tailorbird stitching its leaf-cradle or the collective industry of sociable weavers constructing their haystack apartment block. We marvel at the torrent duck raising its chicks in a foaming Andean cataract or the greater honeyguide leading honey gatherers to a bees nest. And we gasp with incredulity at the male emperor penguin that incubates an egg on its feet above the Antarctic ice or the common swift that can stay airborne for over a year without once touching down.

Among this astounding variety, some bird species have found their lives interwoven with our own. These include those that we have harvested as a resource, whether for their meat, eggs or feathers, or have exploited through domestication on a vast scale none more so than the domestic hen, whose wild red junglefowl ancestor still roams the forests of southern Asia. They also include synanthropic species that have adapted to the human landscape, from alpine choughs flocking to Swiss ski resorts to purple martins adopting multi-storey nest boxes in American backyards.

The most celebrated among all these species are those that we have elevated to cultural icons, bringing an anthropomorphic take to their perceived attributes, such as beauty, strength or intelligence. Thus, species as diverse as the purple-crested turaco (Eswatini) and brahminy kite (India) have acquired royal or even divine associations in their respective parts of the world, while others, such as the kiwi and bald eagle, are universally recognized as national emblems, embodying the pride of an entire nation.