AUTHORS NOTE

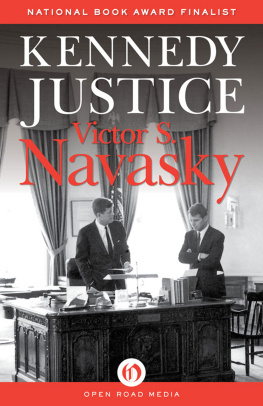

KENNEDY JUSTICE IS NEITHER a personal portrait nor an attempt at chronological reconstruction of the historical high and low points of the Justice Department under Robert F. Kennedy. Rather, it is a series of forays into what is forbiddingly known as the Decision-making Process, a look at how an institution makes up its mind, a tracing of one mans attempt to translate policy values into results, an inquiry into how justice is or isnt done. It is the premise of this book that as the Presidents brother, Robert Kennedy had a chance to be the maximum Attorney General, to explore the outermost reaches of that office, and that therefore Robert Kennedys Attorney Generalship provides a unique opportunity to focus on the points at which the pursuit and exercise of power meet bureaucratic resistanceand to ask what are the consequences of that conflict.

Toward that end I have resisted the temptation to cover such extracurricular activities as the Cuban missile crisis, Robert Kennedys post-Bay of Pigs role as CIA watchdog and promoter of counterinsurgency in Vietnam, and his trips around the world, which collectively took up about half of Kennedys time during his years at Justice. Consistent with that endbut in addition because I did not know Robert Kennedy wellI have also done my best not to indulge any long-range psychoanalysis or motivation-spelunking, except where it seemed essential to develop the issue under investigation, as in the discussion of bugging and wiretapping. Nor have I pretended to any sort of systematic coverage of those areas of the Justice Departments business such as anti-trust and internal security that did not have Robert Kennedys interest. Finally, I have not dealt at any length with the period after President Kennedys assassination but before Robert Kennedys resignation as Attorney General (November 22, 1963September 3, 1964), when the conditions for Robert Kennedys exercise of optimal power no longer applied. This has meant omitting extended consideration of his role in what many may consider a hallmark of his Attorney Generalshipothers give Lyndon B. Johnson the major creditthe Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was formulated largely on RFKs initiative in the spring of 1963 but not passed until the spring of 1964.

Kennedy Justice is not an insiders book, but neither is it an outsiders. When I started my research in early 1966, Kennedy tried to discourage me from writing it, and one of his old Justice Department colleagues went so far as to inform my then-publisher that I would receive no cooperation. Then, when they became persuaded that I was proceeding anyway, I received arms-length cooperation, which in a way was worse than none, since I would travel great distances only to be told what I could have found out in the local library. After about a year and a half of that, I started running into Senator Kennedy at various functions, and although he had not yet agreed to an interview, he would say, Have you found out anything good about me yet? or I understand you saw so-and-so last weekyoure working very hard, arent you? Eventually he told me he would be happy to help in any way he could, and by that timelate 1967I had my guard up, so I suggested we commence serious interviews as soon as I had completed my basic reading and research. By March 1968, when I was ready to interview him, he was ready to run for President, and although we did have some talks which were quite useful to me, we never really got to know each other. I did get to know some of the Kennedy Justice people, though, and after his sad death many of them were imprudently helpful in their reminiscences and in guiding me through the random source material to which they had access.

My experience with the FBI was more consistent. From the day I started till the day I finished, the FBI declined to assist me in any way. When Clifford Sessions, then Director of Public Information of the Justice Department, called his FBI counterpart in Crime Records (the FBIs public relations office) to arrange an appointment, he was told that they preferred not to talk with me. When he asked why, he was told that I might ask questions they did not want to answer. I have tried not to let issues of access prejudice matters of substance, but inescapably my perspective has been shaped by my experience. For instance, my hypothesis that to understand the FBI it helps to think of it as a secret society was stimulated in part by my own exposure to the quaint rituals of the Bureaus Crime Records office, which considers its job more to withhold than to provide information.

Because this is not an authorized account, I have had only ad hoc access to confidential memoranda, files and correspondence. Thus I have occasionally resorted to speculation (identified as such when used) where reportage would have been preferable. Because this is an interim report rather than a definitive one, (which can be undertaken only after both the Kennedy and J. Edgar Hoover papers, among others, are made available) I have felt no compulsion to rehash old material except where it contributes to understanding the new, nor have I gone out of my way to document the original with the familiar. Unless otherwise indicated in the text or notes, the sources of all direct quotes or paraphrases are personal interviews which I have conducted over the past five years. In some cases interviewees requested anonymity and I, of course, have respected that. Upon publication of Kennedy Justice, I am turning my papers over to the John F. Kennedy Library, where they will be available for inspection after an appropriate interval.

A note on usage: Because that is what they were called in the U.S. Department of Justice, 19611964, I call the Attorney General General, the Director of the FBI the Director, and blacks Negroes.

V.S.N.

PROLOGUEThe Attorney General

THE TENSION BETWEEN LAW and politics dominates what little literature there is on the United States Department of Justice, and it was not absent from the Kennedy Justice Department, which was headed by the Presidents political campaign manager but staffed at the top with an elite corps of lawyers lawyers. The current and previous Attorneys GeneralJohn Mitchell with his political commitment to law and order (code words for cracking down on crime at the expense of traditional procedures) and Ramsey Clark, with his purist commitment to procedural integritysymbolize the polar tendencies that coexisted in Kennedy Justice. Robert Kennedys personal appointment was in the political tradition, but he staffed the Department in the legal tradition.

The tension between private values and public standards is as old as Aristotles question about whether the virtue of a good man is the same as that of a good citizen. How, for instance, did a man of Robert Kennedys incorruptible self-image reconcile conflicts between loyalty (ranked high in the Kennedy value hierarchy) and duty? Conversely, consider Kennedys prosecutionhis critics call it persecutionof Jimmy Hoffa. To what extent may a public law enforcer permit his private estimate of evil to intrude on that legal no mans land known as prosecutors discretion?

Nor is there anything new in the tension between the policy maker and the bureaucracyexcept that in this case the policy maker happened to be a Kennedy and the bureaucracy happened to include the FBI. Kennedys, as the ongoing flood of Kennedy literature attests, are good copy, and the fascination they hold for analysts of the American political systemeven those who consider the Kennedys a triumph of style over substancecannot be explained by reference to Kennedy glamour or to the publics remarkable appetite for Kennedy gossip. Rather, Kennedys make interesting case studies at least in part because the conflicts that defined them to some degree anticipated the tensions that surrounded them. They embodied the dilemmas that confronted them. Robert Kennedy at the Justice Department was a prime example. He commuted between idealism and expediency. He valued toughness but was inhabited by compassion. He had a sense of purpose informed by Harvard and a sense of method informed by the ward politics of Irish Boston. Puritanism coexisted with pragmatism; he always knew what he wanted, yet his values were ever evolving.