C ONTENTS

V ICTOR H UGO

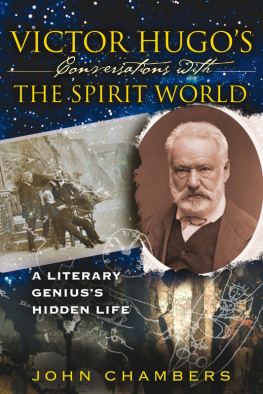

Victor-Marie Hugo was born in Besanon in 1802, the third and youngest son of Lopold Hugo, an officer in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic armies, and his wife, Sophie. The family followed Major Hugo to Italy, Elba, Corsica, and finally Spain, where Lopold rose to the rank of general thanks to the protection of Joseph Bonaparte, whom Napolon had installed on the throne in Madrid. The Hugos marriage, however, was an unhappy one, and Madame Hugo left her husband for good in 1812, returning to Paris with their three sons. Madame Hugo blamed the collapse of the marriage on her royalist principles, a polite half-truth that her poet son echoedfamously describing himself as the son of my father the old soldier, and my mother the Vendennebut in fact their separation was due to far more banal causes. Sophie Hugo saw to it that her sons received an excellent education, which included the great works of French and classical literature, as well as political writings in sympathy with their mothers beliefs. Victor and his two elder brothers were largely estranged from their father until their mothers death in 1821.

Young Victor displayed a precocious literary talent while still in his teens, winning prizes for his poems and even founding, with his brothers, a literary magazine entitled Le Conservateur littraire. He was barely twenty when he published his first collection of verse, Odes et posies diverses, which earned him a national reputation and a royal pension that allowed him to marry Adle Foucher, who had been his playmate as a child. In 1825, Hugo was named to the Legion of Honour, and invited to be the official poet of the coronation of Charles X, youngest brother of Louis XVI and the last Bourbon king of France.

But Hugos youthful royalism quickly gave way to a growing liberalism. The famous preface to his play Cromwell became a manifesto for a generation of French Romantics. In 1829 he published a remarkable novel, Le Dernier Jour dun condamn (The Last Day of a Condemned Man), which was an eloquent denunciation of the death penalty (a lifelong cause of Hugos), and his poetry began to show more political ambiguity than had been evident in his earlier work. In the history of French literature, the legendary bataille dHernaniwhen the Parisian literary and political worlds were divided between pro- and anti-Hugo campsmarks the triumph of Romanticism in nineteenth-century France. Hugos play broke with all the rules of the neoclassical tradition that had dominated French theatre. There were literally fistfights in the audience between Romantics and conservatives. In retrospect, the bataille dHernani came to be viewed as a cultural precursor of the Revolution of 1830.

Under the July Monarchy of 183048, Hugos status as the leading figure in French literature increased steadily as he successfully published the novel Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) as well as several collections of poetry, including Les Feuilles dautomne (1831), Les Chants du crpuscule (1835), Les Voix intrieures (1837), and Les Rayons et les ombres (1840); he also enjoyed considerable success as a playwright. Even after he became a member of the literary establishment, Hugos work continued to reveal a growing concern for social justice. In 1834, he published Claude Gueux, a brief account of a murderer who went to the guillotine; Hugo used his book to dare his bourgeois readers to consider their responsibility for a society that drove men to crime, and women to prostitution. In his poetry too, amid Romantic contemplations of nature and celebrations of his love for his children or his mistress, Hugos social and political conscience is clearly present. Publicly, the 1840s brought Hugo to new professional and political heights, as he was elected to the Acadmie Franaise and named by the king to the Chambre des Pairs. Personally, Hugo was devastated in 1843 by the sudden death by drowning of his eldest and favourite child, Lopoldine, a loss that would inspire some of his best-known poems.

It was in 1845 that he began work on a novel, first called Jean Trjean renamed Les Misres, the story of a convict, a poor man persecuted by a system in which justice has been overshadowed by the law. Hugo had completed most of the book when the Revolution of 1848 drew him back into politics. Elected to the new National Assembly of the nascent Second Republic as a member of the centre-right, Hugo was soon calling for such progressive measures as free public education, penal reform, including the abolition of the death penalty, and international cooperation. In June of 1848, Hugo played a leading role in the suppression of a popular insurrection that saw barricades raised up in the streets of Paris. It was a searing moment for Hugo, who was appalled by the misery that provoked the uprising, but felt compelled to side with civic order. Hugo also supported the return from exile of Napolons nephew Louis-Napolon Bonaparte, as well as his subsequent candidacy for the presidency. By the time the so-called prince-prsident seized power as Emperor Napolon III, Hugo had become one of his most vocal and courageous opponents. Hugo soon judged it prudent to leave France, eventually taking up residence in the English Channel Islands, where he would await the fall of the Second Empire for almost twenty years.

It was in exile that Hugos political transformation became complete. The poetry he wrote in exileLes Chtiments, La Lgende des sicles, La Fin de Satanwas politically and artistically daring, and revealed a greater commitment to changing the social order of France and Europe than his previous writings. Hugo also publicly lent his support to such movements as abolitionism in the United States and Italian unification under Garibaldi. This was the Hugo who in 1860 returned to Les Misres, which he had given up for politics in 1848. In 1861, sixteen years after he began, and with significant revisions to his original, unfinished novel, Hugo travelled to Belgium, where the book now called Les Misrables was to be published, and visited the battlefield of Waterloo, in order to verify certain details for a brief digression he intended to include in his novel. A massive publicity campaign in every capital of Europe preceded the publication of the first volume, Fantine, in April 1862. The Parisian literary establishment did not quite know what to make of the novel, which defied every expectation of the genre. Critical reaction was typified by the Goncourt brothers pronouncement that a man of genius had written a novel intended for the cabinets de lecture (i.e., the uneducated people who visited the reading rooms). Such cautious snobbery was not reflected in the books sales. In Paris, bookstores sold every copy within three days. Factory workers were reported to have pooled their money to buy shared copies. Conservatives denounced a book that presented a criminal as a hero. Pope Pius IX placed Les Misrables on the Churchs Index of proscribed books, and copies were publicly burned in Spain. In Paris and all around the world, Les Misrables solidified Hugos reputation as the champion of the poor and the enemy of tyranny. The novel was devoured by everyone from Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky to soldiers on both sides of the American Civil War.

When the Franco-Prussian War brought down the government of the Second Empire, Hugo returned to France, his status as a national icon unquestioned. He served again in government, the last time as a senator of the Third Republic. He also continued to write, including a sentimental verse collection entitled