First published in 1977 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

This edition first published in 2022

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1977 Julian Cornwall

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-03-203038-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-00-319086-8 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-03-204380-7 (Volume 22) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-03-204385-2 (Volume 22) (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-00-319294-7 (Volume 22) (ebk)

DOI: 10.4324/9781003192947

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

First published in 1977

by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

39 Store Street,

London WC1E 7DD,

Broadway House,

Newtown Road,

Henley-on-Thames,

Oxon RG 9 1EN and

9 Park Street,

Boston, Mass. 02108, USA

Set in IBM Press Roman by

Express Litho Service (Oxford)

and printed in Great Britain by

Redwood Burn Ltd

Trowbridge and Esher

Julian Cornwall 1977

No part of this book may be reproduced in

any form without permission from the

publisher, except for the quotation of brief

passages in criticism

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Cornwall, Julian

Revolt of the peasantry, 1549.

1. Peasant uprisings - England 2. Ketts Rebellion,

1549 3. Great Britain - History - Edward VI,

1547-1553

I. Title

942.053 DA345 77-30119

ISBN 0 7100 86768

To Margaret

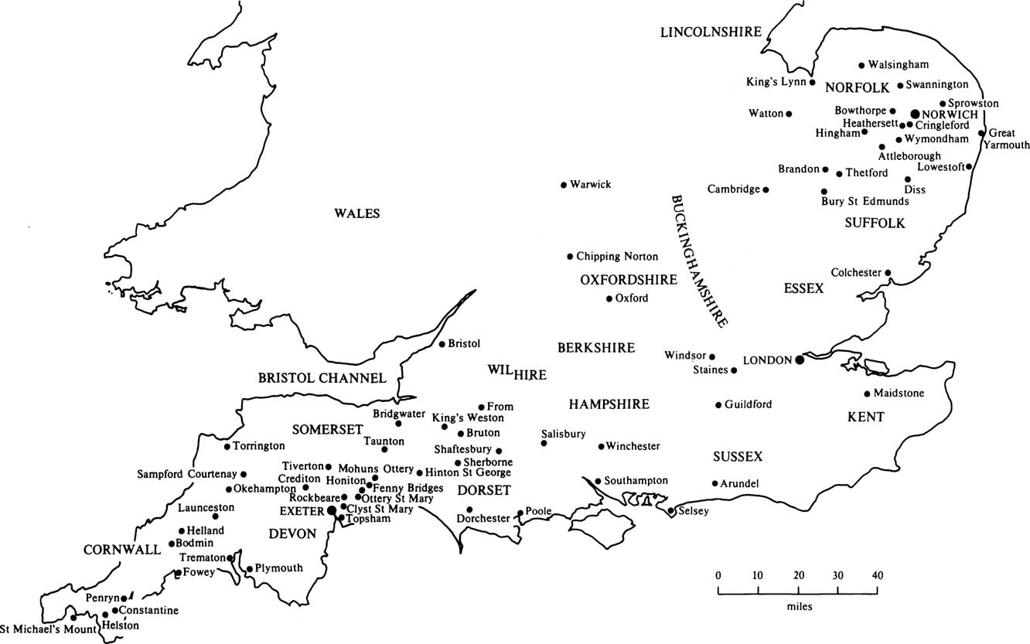

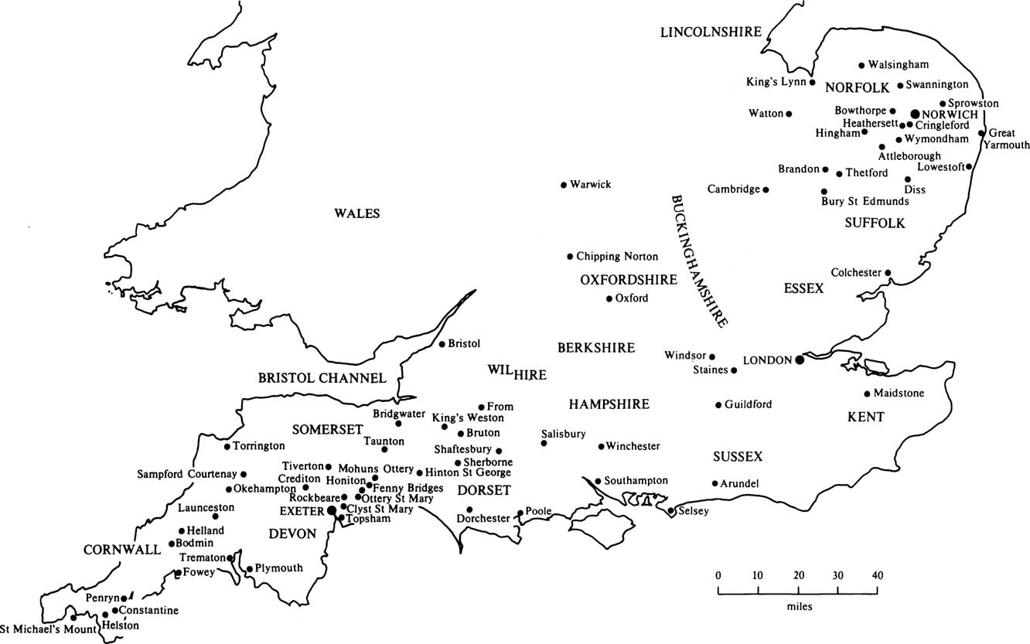

Maps

1 Southern England

2 Norwich

3 The Battle of Clyst St Mary

4 The Battle of Sampford Courtenay - first phase

I am greatly indebted to my colleague David Stephenson for reading and commenting on the draft, to Jack Millar of Longwood College, Virginia, for advice on military details, and most of all to my wife who compiled the index and generally encouraged me to complete the work.

I

The two rebellions which convulsed England in the summer of 1549 are well trodden ground for students of sixteenth-century history, although much less familiar to the wider reading public, sometimes amounting to little better than dimly recollected facts from some long-forgotten school lesson. These episodes deserve to be better known. In the writing of history nowadays there is a significant trend away from exclusive preoccupation with affairs of state towards a greater emphasis on the lives and struggles of ordinary people. Oddly enough, popular history designed for mass consumption has yet to catch up with this development. Recent television excursions into the Tudor age have been devoted exclusively to the lives of three of the monarchs, Henry VII, Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. It is of further interest to observe the neglect of the stormy and fascinating 11 years which separated the reigns of the two latter rulers when the throne was occupied successively by a sickly child and a faded middle-aged woman: an unglamorous interlude in a romantic epoch! And not only is it accepted that the history of England comprehended the country as well as the court, it is also recognised that the kingdom was in many respects the sum of the counties, each of which to a greater or lesser degree constituted a self-conscious community in its own right. Until at least the second half of the seventeenth century it is necessary to pursue the history of the nation through the structure and activities of these local communities. Both the risings of 1549 were motivated primarily by local issues.

In contrast with the opening and closing decades, the middle 30 years or so of the sixteenth century were restless and intermittently violent. Not the least of the achievements of the founders of the Tudor dynasty was the liberating of England from the scourge of civil strife. Apart from one brief flare-up in 1487, the accession of Henry VII had terminated the armed struggles for possession of the Crown commonly known as the Wars of the Roses. Subsequent upsurges of violence during his reign took the form of resistance in remote regions to his policy of enforcing uniform administration throughout the realm, and were specifically protests against taxation. Only the two Cornish risings of 1497 involved fighting on any scale, and after they had been crushed the nation enjoyed relative freedom from disorder for almost four decades until, in 1536, a serious rebellion broke out in the North, to be followed by four more during the next 33 years, with no less than three in the space of five years 154954.

The Pilgrimage of Grace began in Lincolnshire in October 1536 as a rising of the peasants provoked by a variety of causes of which the most immediate were taxes and hostility to the dissolution of the monasteries. It came to nothing. Several thousands of sketchily armed country people wandered about the Parts of Lindsey for a few days accompanied, perhaps reluctantly, by a handful of gentlemen, and eventually came to a stop outside the walls of Lincoln which refused to open its gates and make common cause with them. Then, as hastily assembled royal forces began to converge on them, the gentlemen seized the opportunity to decamp, leaving the peasants leaderless, with nothing to do but disperse.

Meanwhile the revolt had spread to Yorkshire where a potentially far more menacing movement developed. Similarly originating in a medley of local grievances, largely economic in character, coupled with reaction against Henry VIIIs policy towards the Church, which had just culminated in the deprivation of the county of a large number of religious houses, the Pilgrimage drew in not merely the common folk, but the gentry as well, found a dissident peer, Lord Darcy, to lead it, and an able organiser and articulate spokesman in a lawyer named Robert Aske. Momentarily too weak to confront the insurgents, the Kings Lieutenant, the duke of Norfolk, had no recourse but to negotiate. Fortunately they did not aspire to overthrow the government, indeed the gentry were soon looking for a pretext to back down, and willingly accepted promises which effectively bound the King to nothing. In the end all the rising seemed to have proved was that it was impossible to mount a successful challenge to Henry VIII or deflect him from his course. In retrospect it was bound to fail against a rgime which, despite (maybe because of) its despotic complexion, commanded the loyalty of the majority of the nation.