THE SOLDIER WHO CHECKED US OUT at a border roadblock, heading to Belfast on North One, would have been claimed by some page of a police Gazette as a constable, but he was a soldier nevertheless, with pectoral armor-pads, an abdominal plate, a Magnum SLR at the diagonal, all of which made walking anywhere a matter of great deliberateness for him. His position on the roadway was plotted to keep clear three lines of fire: from a sentry at the barrack doorway, from an alert squad at the boom gate, and from gun-slits in the emplacement beside. A cockeyed farm-truck, trailing sawdust, was allowed through, but a station-wagon was being unloaded here by a tolerant young woman whose children bounced the seat in the back. Their luggage included a picnic hamper and a yellow pedal-car.

The guard seemed to me to take in the windscreen sticker of the Dublin hire-car company, and thereafter to have eyes only for Seamus Deane, who lounged on the passenger seat, his jacket now disarmingly open. This soldiers distrust I cannot account for, but its accuracy was astonishing because Seamus was not Dublin Irish but a northerner, raised in the Catholic quarter of Derry, and so the routine antagonist of every border guard in the Royal Ulster Constabulary. His business in Belfast included a lecture about the ways of forcing the British from Northern Ireland. It was scheduled for this evening, at a Community Centre deep in Republican territory off the Falls Road. But his bearing now must have carried the dignity of his other vocation, which was Professor of English and American Literature at University College, Dublin, for the guard scanned the back seat and ordered us on. If Seamus was worried that his papers mightnt bear inspection without trouble, he could have taken it easy. We didnt know it then, but his lecture notes presently lay on his desk at home. We had nothing in the back of the automobile subversive of the British government in Ulster. He knew the arguments well enough, anyway, to deliver them in faultless ex tempore. The contraband, if we carried any at all, was Seamus.

We drove the next five miles north for the most part in silence, then wound into a township, the streets tight, the buildings stony and tall. This was Newry. Here McLoughlan, King of Ireland, built an Abbey in the twelfth century which became a college for secular priests four hundred years later. Newry Castle fell to Edward Bruce in 1315. St Patricks, completed here in the late 1500s, was the first Protestant church in Ireland. And it was at Newry, one night during later Troubles, that the Black and Tans executed Catholics in a warning to other recidivist townships. The barracks here have been a favoured target for IRA mortars ever since. These facts Seamus delivered as passionlessly as a historian. We broke free of the shadowy streets, the pale sun lit the Meadows, soft and green, the most beautiful in all Ireland. Seamus flung out an expansive arm. County Down, he said, gateway to the Irish North. He was smiling

THE FLAGS OF EUROPE were once banners of religion, before ever they were the standards of nationhood, but this slow transition to the secular seemed to have suffered a reverse in the Loyalist suburbs of Belfast, anyway those near the division known as the Donegal Pass, where small Union Jacks fluttered on the balconies of the narrow terraces, and these were flying here not so much because this is British territory, aloft as the flag of the nation, but because those who fly it are Protestants. Here and there they flowered on doorways from door-handles and door-knockers like blooms in buttonholes on Days of Remembrance, and the day they were in remembrance of was barely three months past, the day the government of the United Kingdom effected the Anglo-Irish Agreement, and in Northern affairs Ireland was given the status of casual consultants. A sell-out, so the Reverend Ian Paisley called it the same day, a sell-out of the Loyalist majority of Ulster. In the listening crowd, some waved Union Jacks by way of applause. Others held a purer version, which had stripped off the Cross of St Andrew and the Cross of St Patrick, leaving only a white field with the red Cross of St George. And here now, alongside streets off the Donegal Road, this Cross marked houses of the fiercest Loyalists. For the Brotherhood of the Loyal Orange Lodges, whose banner it also is, the Cross carries a more covert message: St George, whose acts are known only to God.

A sedan on lowered springs and Michelin Fats drew alongside, held level while two young men in the back seat looked us over, and pulled ahead. Seamus put this down to our southern registration. I wondered if scrutiny is always so blatant around Belfast. You will get the hang of it, he shrugged. Safe driving means something else here.

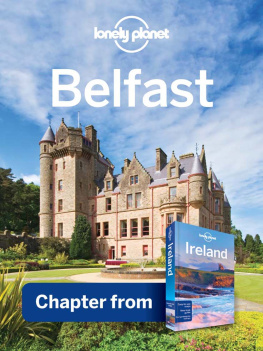

Downtown was quiet and we made the city centre as the street lamps lit, as church bells were calling on Evensong. Great Victoria Street is an avenue of academic colleges, banks, shops, saloons with smoky glass, and most of them carry, still, the graces of last century, but at the Forum Hotel the charm ran out. It was fenced from the sidewalk by a chain-wire palisade, arc lamps bleached the parking lot, and visitors were frisked at the sentry box. We pulled up at a boom gate. Seamus asked who it was recommended I stay here, and I confessed I had been no smarter than to rely on a travel agency. It used to be called the Europa, he said. The Europa was the most bombed hotel in Ireland.

The choice of Forum indicated a new effort at neutrality, and the present management had given some thought to the arrangement of flags in the forecourt. The United States of America was prominent. But the other standards seemed to carry a separate message. Maybe this was merely in error, like a misprint in semaphore, but here were Britain, the Netherlands, France and Denmark, all of them nations from which William drew units for the Battle of the Boyne.

WE LIVE IN A CRYPTIC WORLD I overheard a Belfast writer say later in the week, delivering a message which was itself cryptic, since he said it as an aside but for me to hear, and anyway it would be a mistake to translate world in anything like its normal sense because the codes he was referring to were the ways in which Belfast communities speak to each other, and the ways they speak to the rest of the world are quite different. But the message benefits by a few days anachronism, to bring it forward to the night we walked into a building in Ballymurphy, Catholic territory, where Seamus was to give his lecture. The peep-hole blinked, the door opened, and Seamus was swept up in the embrace of a warm pot-bellied stove of a woman who then led us to soup from a stall set up in the corridor. She was Sheilagh, and the news she had for Seamus overcame her welcome. Soldiers had raided the place, mid-morning, looking for certain young men on the run. Were they RUC or British soldiers? Seamus asked. Sheilagh said British, who claimed that the centre was working as a haven. Seamus shook his head as if a slander of such magnitude might be actionable at law. Oh, a terrible thing, he said.