Among

the

Very Foreign

John Bryson

His Brow in Feathers, the Dyak Chieftain and His Equation for the Order of Time.

Bugis Street Shoes.

A Good Pirate Crew Can Swarm Sitting Down.

Borneo Ferry.

Parties All Over Town.

Published by John N. Bryson

First published 2013

John N. Bryson

Among the Very Foreign

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright restricted above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

ISBN: 978-1-922219-34-3 (ePub)

Digital Distribution: Ebook Alchemy

His Brow in Feathers, the Dyak Chieftain & His Equation for the Order of Time

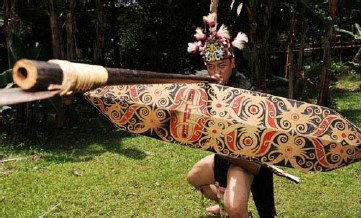

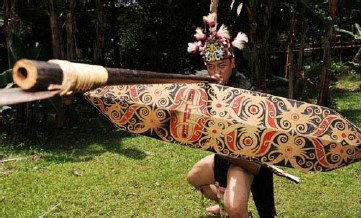

HIS BROW IN FEATHERS, plumage of the divine bird which one-time flew from the heavens to the ancients of his tribe with news of the coming Sanskrit Empire and then died fluttering at their feet as the Gods slew it in warning to the mortal world, his chiefly tunicle azure thrummed sequined with pearl-shell traded upstream from the coast in Arab dhows two hundred years before the birth of Islam, his necklace of turquoise stringing together the whittled effigies of ancestors to which another would be added upon his death, hanging to the cummerbund of loincloth woven with coriander for its scented breath, its midriff plate clasped with the claws of the Sun Bear, and rimmed with the tusks of a boar so long extinct that it no longer has a place in the known stories, all this signifying, in the intricate heraldry of Benuaq belief, his high birth, wisdom, benediction, grace, wealth and valour, he watched our arrival by prau across his lake, his vantage the highest parapet of the prayer tower, the better to judge if we might be carrying some threat to the Order of Time.

HIS LAKE WAS ONCE A MOUNTAIN, which inverted its form in an act of compassion for people who were without fishing grounds. The people are grateful. They understand the force of will in such a feat. So fiercely did the effort compress its foundations that the bedrock ruptured, its rich blood ran, and the broad water here is forever crimson.

The butterflies became shrimp. The birds became fish. The crowns of mountaintop trees lived on as flowering lotus, now free swimming, their pale roots webbed like the feet of duck, paddling in search of the sweetest currents. As in the skies, the fish which were once birds fly to the trees which are now lotus so the Dyak fishermen corral this foliage together, they drive stakes deep into the lake bed to fashion aviaries as large as islands, and the channels leading toward the shoreline pass between these gardens, where praus dry their nets aloft on booms as if they were windless sails.

ON THE APPROACH OF STRANGERS, the People Benuaq stand. The faces of fishermen are bound with cloth, the faces of the women are pale with daub. The way ashore is a narrow glide through a floating marketplace, between the pontoons and thatches, where the stilled crowds watch, and the heaped sprats drying on the slats are as silver as coin.

The Benuaq line with the waters edge, where their village lifts from the lake on stilts in deference to the power of the Monsoon Spirit, they watch from the footways which climb to the long-house, and their gaze is on the reliable sorcery of the shoals below. If plants in the shallows curl from the path of wading visitors, the judgment of lily and of cress will pass through the people like a trill of disgust.

But should it rain hard soon after landfall, as when my son and I stood waiting on some gesture of invitation, this is a great fortune. The pathway here is a sacred trust. The mountain behind the village is the Peak of the Dead, which is the Afterlife and the route must be guarded. Sometimes travellers who mean harm will pass this way. The People Benuaq understand that a rain-burst carries a blessing from the God Belare, who rides the clouds mouthing thunderbolts and sees deep into the human heart, so here the strangers intentions are pure, the sun lights the streaming palms, the wicker huts, the swilling beach, and the crowd will draw aside for the passage of a foot runner, emissary from the pleased elders.

COCKFIGHTING SIGNIFIES the beauty of heroic death. Wing and claw adorn the imagination of warriors and of artists. Refined to line and to colour, the glorious plume and the pitiless beak embroider sword handles, the skirts of dancing women, and the canopies above the thrones of honour.

Sit, the chieftain said. He was carrying a lolling cockerel, which he robbed of its senses by passing his fingers across its gaze. He sat with it on his lap.

This lad is your young friend? He asked.

My son, I said, Matiu.

Ah. A wise son, to walk with his father. My own eldest is far, he said.

The sun had dried the kampong and the feet of the dancers were making dust. They circled the thrones in gentle step, the toes and the fingers arched in piety to the gracefulness of human form, every hand trailing high a saffron scarf, held tight between finger and thumb to prevent its flight to the skies. A golden sunrise is the aggregate of all enchanted scarves lost by maidens since the world began.

The lesson of artistry, the chieftain said, is this: by favour of the Gods, not everything obeys the rules of the physical world.

The strokes of musicians, crouching at gong and drum, were repeated behind them in the hands of young prodigies. Small girls stepped to the dance in serious concert. The Benuaq were now so many that they filled the pathways beside the huts and pressed between stilts under the longhouse. The veranda above was the privilege of the high born and the godly, and from here three sorcerers descended the notched log to the stage floor carrying, in earthen pots, the pickled placenta of miscarriage and the bones of stillborn children, laid now before the tall post carved with care to resemble no known form, the Empty Image which imprisons, for all the time, vagrant spirits of evil.

The line of dancers coiled, to the gongs a circle, to the drums a spiral, and a slim girl broke ranks with a headband for Matthew, amused by the length of his hair. Her face was powdered with the eggshell blue of the speckled mallard. She wanted him to dance. The chieftain approve of this. She was his daughter. Her name was Mili. Milis mother was married to the finest maker of parangs, lances and blowpipes in the village.

A noble child was my gift to the husband, the chieftain said.

HIS LANGUAGES took in English and Dutch, both the inheritance of colonial times in Borneo, and together they helped his German; he was raised on four versions of Dyak, which he refused to call dialects because he considered them insufficiently similar; Indonesian and Malay were so allied that he scored them as one, but his poor showing with Javanese most astonished him about himself. This he attributed to a dislike of the forced resettlement program, the transmigrasi, which plucked Javanese communities from their homelands and implanted them in villages laid out like groves all along the Mahakam River. He saw a heresy in this rearrangement, a bid to alter the order of time.

As a warning against scepticism he tapped his mahogany forehead. His eyes were serene and unyielding, for he was confident of his ground on this point. The accurate order of time is as precious to life as it is to music and song.