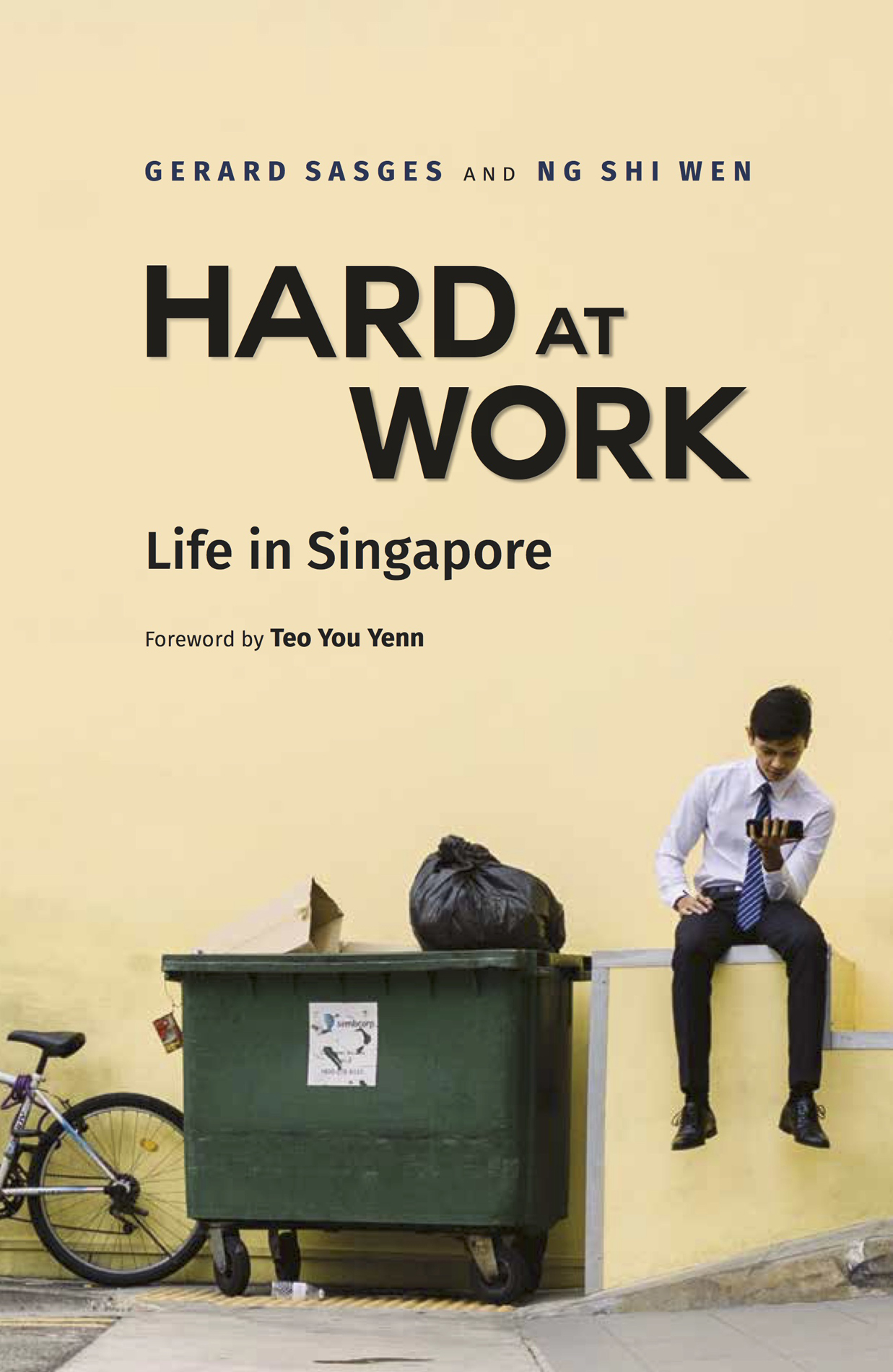

Edited by Gerard Sasges and Ng Shi Wen

Photographs by Ng Shi Wen

Foreword by Teo You Yenn

2019 Gerard Sasges and Ng Shi Wen

Published under the Ridge Books imprint by:

NUS Press

National University of Singapore

AS3-01-02, 3 Arts Link

Singapore 117569

Fax: (65) 6774-0652

E-mail:

Website: http://nuspress.nus.edu.sg

Ebook ISBN 978-981-3251-33-5

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission from the Publisher.

National Library Board, Singapore Cataloguing in Publication Data

Name(s): Sasges, Gerard. | Ng, Shi Wen, author.

Title: Hard at work : life in Singapore / Gerard Sasges & Ng Shi Wen.

Description: Singapore : Ridge Books, [2019]

Identifier(s): OCN 1090190815 | ISBN 978-981-3250-50-5 (paperback)

Subject(s): LCSH: Labor--Singapore. | Work--Social aspects--Singapore. | Working class--Singapore. | Singapore--Social conditions--21st century.

Classification: DDC 306.36095957--dc23

CONTENTS

Cities hum. For people who live in them, the humming is a kind of complex ugly beauty. It is magnetic it draws one in, and becomes a kind of life force that keeps one there. Descriptions of cities often focus on their status as financial hubs, shiny skylines, and the various consumption choices they offer. Living within, city-dwellers are tethered to something else less glamorous, cast in shades and shadows, harder to describe, too messy to put ones finger on.

I remember being mesmerised as a kid by Richard Scarrys books the ones where buildings are bisected so that you get to see their cross-sections and be privy to everyone doing busy work in them; where every inch of road is filled with busy creatures, busy-ing away at various occupations. There is so much doing in a city so many specialties and trades, so much busy-ness in the air, at once utterly chaotic and somehow magically harmonious. Connectedness and isolation, noise and quiet, conflict and conviviality, and it all comes together to produce something that is the city, humming along, more than the sum of its parts.

The interviews and accompanying photographs in Hard at Work, when I explored them as a collection, remind me of the childhood pleasure of scrutinising those busy pictures. The book is a rarity for presenting relatively raw data. The interview transcripts are lightly edited; analysis is eschewed and in its place the interviews are subtly organised to leave space for meandering, discovery, with rewards at multiple turns. Venture a few steps and face direct revelations about the nature of jobs that every city-dweller takes for granted cleaner, bus captain, doctor, postal worker. Take a few more steps and be surprised a teacher turns out to have an unexpected story; you encounter a pet crematorium worker, a monk, a bet collector, a law student with a part-time job his classmates cannot begin to imagine. We find too, as we meander, evocative photographs that are hard to look away from, so rare it is to see so much backstage. The images remind us of the corporeal realities that make up our days and hours, as well as the significance of ordinary spaces and everyday acts in bringing into being that which we share in a city.

Reading the stories, we see dreams some broken, others being chased; we witness craft, expertise, and the corresponding beauty of people taking pride in their labour. Against the backdrop of relentless national discourses in Singapore that privilege straight and narrow pathways, we meet people who reject (or are rejected from) straight paths who turn out to be true path-seekers and pathfinders. Seemingly without being prompted, interviewees speak relentlessly of human connections with family, friends, co-workers, but importantly also with strangers. These human encounters are both persistent and fleeting, sometimes affirming and other times frustrating, and here lie the threads of complex and messy human connections that make a city. Where words end, pixels carry the book forward, sustaining the feeling that this thing were staring at is lit up from many different directions.

Together, the stories reveal the generic engine of any big city, but also the specific engines underlying this particular one. The city of Singapore: a cacophony of languages colliding; we refer to it simply as Singlish but it is not easy to describe to people not of here. Hard at Work, though ostensibly in English, somehow manages to convey, and legitimise, the many sounds and rhythms that make up local language(s). The city of Singapore a city but also a nation state and therefore with particular kinds of borders and boundaries, specific articulations of belonging and otherness. Academics, attuned as we are to certain norms of political correctness, sometimes struggle with describing these, but ordinary people have no such qualms. In Hard at Work, they cut to the chase with persistent references to ethnic, religious, national difference one wants to sum it up as diversity, but the word does not do justice to the picture that emerges as the collection of interviews unfold. Most big cities are diverse places, but these are heightened tensions and contradictions of a city that also feels compelled to guard its borders in order to simultaneously be a nation. The city of Singapore: a city governed with a strong hand. No one appears to ask about the government, but it pops up everywhere. City-dwellers who hum but watch their back; city-dwellers who buzz, unheard; city-dwellers who search for gaps, spaces, because sometimes that is all one can do. Together, the stories bring comfort, a sigh of relief, because here is a city I finally recognise, not a city one is supposed to conjure in ones imagination Global City passion made possible but a city, and country, real in its complex ugly beauty.

There are two jobs hidden from view in Hard at Work: Professor and Ethnographer. In both cases, the authors embody craft and expertise, commitment and pride. Like the many people interviewed, they take their work seriously, and have made something solid and durable in the process. I see only the final product, so this is me reverse engineering: The Professor gave his students tools of the trade these are the questions to ask when we think about what work is, here is how you approach strangers, this is how you should ask questions, this is the way to listen, these are the ethics of conducting yourself as an interviewer, as a human being. The Professor looked at his students work and recognised value, their potential contribution to knowledge-production. He went beyond grading assignments to what must have been deep labour of conceptualisation, selection, editing, organisation. A product that ends up looking elegant and effortless usually entails intense labour like making a garment so that its stitches do not show.

The Ethnographer, in this highly unusual case, is a composite of many students and a photographer. They brought their openness and curiosity to the field, suspending judgement to cede space for their interviewees. They asked and they observed and they listened simple tools of the trade, too often unused and which turn out to be what anyone needs to learn more about the world. They used their selves and their tools skillfully: we see this in the sustained candour and occasional meanderings of interviewees stories; in the documentation of quiet, unremarkable, habitual moments embedded in work; and in the aunties and uncles turning the ethnographic gaze around to ask the students questions about their lives.