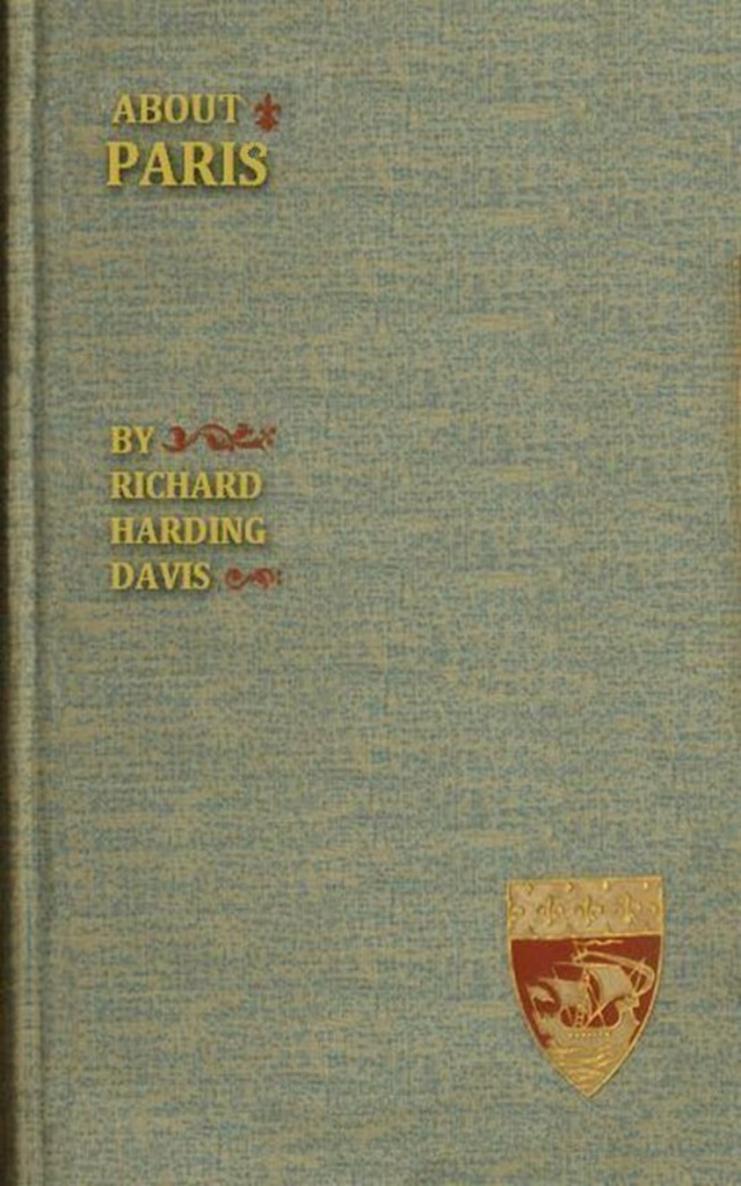

By RICHARD HARDING DAVIS.

OUR ENGLISH COUSINS. Illustrated. Post 8vo,

Cloth, Ornamental, $1 25.

THE RULERS OF THE MEDITERRANEAN.

Illustrated. Post 8vo, Cloth, Ornamental, $1 25.

THE WEST FROM A CAR-WINDOW. Illustrated.

Post 8vo, Cloth, Ornamental, $1 25.

THE EXILES, AND OTHER STORIES. Illustrated.

Post 8vo, Cloth, Ornamental, $1 50.

VAN BIBBER, AND OTHERS. Illustrated. Post

8vo, Cloth, Ornamental, $1 00; Paper, 60 cents.

Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York.

Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

ABOUT PARIS

I

THE STREETS OF PARIS

The street that I knew best in Paris was an unimportant street, and one into which important people seldom came, and then only to pass on through it to the Rue de Rivoli, which ran parallel with it, or to the Rue Castiglione, which cut it evenly in two. It was to them only the shortest distance between two points, for the sidewalks of this street were not sprinkled with damp sawdust and set out with marble-topped tables under red awnings, nor were there the mirrors and windows of jewellers and milliners along its course to make one turn and look. It was interesting only to those people who lived upon it, and to us perhaps only for that reason. If you judged it by the circumstance that we all spent our time in hanging out of the windows, and that the concierge of each house stood continually at the front door, you would suppose it to be a most interesting thoroughfare, in which things were always happening. What did happen was not interesting to the outsider, and you had to live in it some time before you could appreciate the true value of the street. With one exception. This was the great distinction of our street, and one of which we were very proud. A poet had lived in his way, and loved in his way, in one of the houses, and had died there. You could read the simple, unromantic record of this in big black letters on a tablet placed evenly between the two windows of the entresol. It gave a distinguished air to that house, and rendered it different from all of the others, as a Legion of Honor on the breast of a French soldier makes him conspicuous amongst his fellows.

ALFRED DE MUSSET

n Paris

Le 11 Dcembre 1810

est mort

dans cette maison

Le 2 Mai 1857

"THE CONCIERGE OF EACH HOUSE STOOD CONTINUALLY AT THE FRONT DOOR"

We were all pleased when people stopped and read this inscription. We took it as a tribute to the importance of our street, and we felt a proprietary interest in that tablet and in that house, as though this neighborly association with genius was something to our individual credit.

We had other distinguished people in our street, but they were very much alive, and their tablets were colored ones drawn by Chret, and pasted up all over Paris in endless repetition; and though their celebrity may not live as long as has the poet's, while they are living they seem to enjoy life as fully as he did, and to get out of the present all that the present has to give.

The one in which we all took the most interest lived just across the street from me, and by looking up a little you could see her looking out of her window, with her thick, heavy black hair bound in bandeaux across her forehead, and a great diamond horseshoe pinned at her throat, and with just a touch of white powder showing on her nose and cheeks. She looked as though she should have lived by rights in the Faubourg St.-Germain, and she used to smile down rather kindly upon the street with a haughty, tolerant look, as if it amused her by its simplicity and idleness, and by the quietness, which only the cries of the children or of the hucksters, or the cracking at times of a coachman's whip, ever broke. She looked very well then, but it was in the morning that the street saw her at her best. For it was then that she went out to ride in the Bois in her Whitechapel cart, and as she never awoke in time, apparently, we had the satisfaction of watching the pony and the tiger and cart for an hour or two until she came. It was a brown basket-cart, and the tiger used to walk around it many times to see that it had not changed in any particular since he had examined it three minutes before, and the air with which he did this gave us an excellent idea of the responsibility of his position. So that people passing stopped and looked toobakers' boys in white linen caps and with baskets on their arms, and commissionnaires in cocked hats and portfolios chained to their persons, and gentlemen freshly made up for the morning, with waxed mustaches and flat-brimmed high hats, and little girls with plaits, and little boys with bare legs; and all of us in-doors, as soon as we heard the pony stamp his sharp hoofs on the asphalt, would drop books or razors or brooms or mops and wait patiently at the window until she came.

When she came she wore a black habit with fresh white gloves, holding her skirt and crop in one hand, and the crowd would separate on either side of her. She did not see the crowd. She was used to crowds, and she would pat the pony's head or rub his ears with the fresh kid gloves, and tighten the buckle or shift a strap with an air quite as knowing as the tiger's, but not quite so serious. Then she would wrap the lap-robe about her, and her maid would take her place at her side with the spaniel in her arms, and she would give the pony the full length of the lash, and he would go off like a hound out of the leash. They always reached the corner before the tiger was able to overtake them, and I believe it was the hope of seeing him some morning left behind forever which led to the general interest in their departure. And when they had gone, the crowd would look at the empty place in the street, and at each other, and up at us in the windows, and then separate, and the street would grow quiet again. One could see her again later, if one wished, in the evening, riding a great horse around the ring, in another habit, but with the same haughty smile; and as the horse reared on his hind-legs, and kicked and plunged as though he would fall back on her, she would smile at him as she did on the children in our street, with the same unconcerned, amused look that she would have given to a kitten playing with its tail.