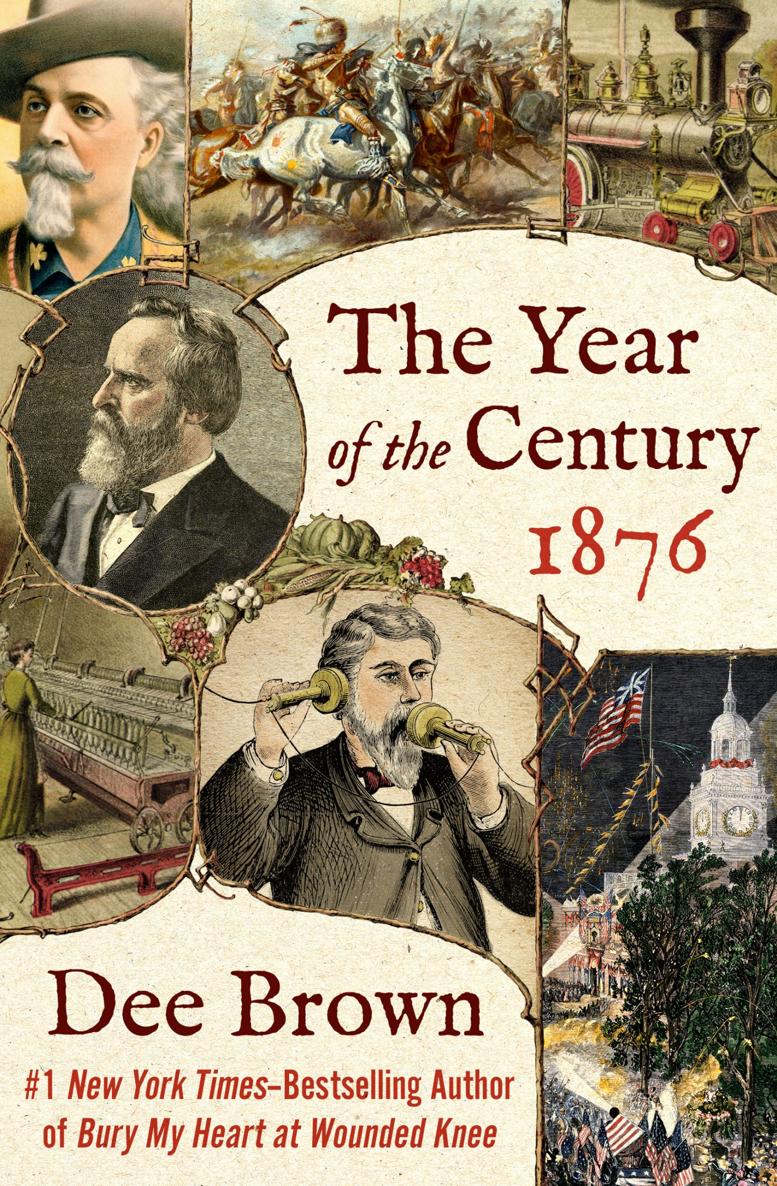

Introduction

THERE IS SOMETHING MAGIC in anniversaries, those arbitrary signposts devised by mortals to chart their passage through the mystery of time. We give special significance to firsts, tens, twenty-fives and fifties, and do reverent honors to the nicely rounded one hundreds. By use of calendars we thus attempt to harness time and derive benefit from it. We set aside allotments of time for meditation, recreation, and achievement. We choose segments of time to mark an ending or a beginning.

In the year 1876 the United States of America, after surviving four wars and a succession of economic and political crises, reached the centennial of its nationhood. Its original population of four million had increased tenfold, drawn from all continents of the earth, a diversity of races, religions and customs such as no other country had ever known. These new Americans were a sentimental, reverent, earthy, skeptical, generous, rowdy, audacious people, with a fervent belief in freedom which they defined in terms as varied as themselves.

Because nations are people they too become trapped in the prison of time, marking off their procession of days, weeks, months and years as proof of progress or robustness, as justification for the schema under which they exist. More often than not there is an artificiality about such commemorations, yet they tend to transform ordinary events into pageantry so that a whole nation becomes mindful of the flow of time, the relationship of the present to past and future. With no competition from such myriad diversions as surround us in the twentieth century, the great fairs and exhibitions of the nineteenth century dominated the national scene during the months of their existence. This was especially true in the centennial year.

In 1876, almost as if by common consent the people of the United States chose the centennial of the nations birth as a year for taking stock of the past by means of celebrations both solemn and gay. The major planned event was a Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, where during the six months from May to November, one of every five Americans came to celebrate the glories of his Republic and to view tangible evidences of its accomplishments.

The centennial arrived in an era when human beings were experiencing the greatest changes in their history. For Americans the changes were so sweeping and came with such speed that few were aware of their meaning for the future. In the span of a few years, Americans had fused a loose collection of states into a Union; they had extended their geographical boundaries from the Atlantic to the Pacific; they had moved from a simple agrarian world into a bewilderingly complex industrial era.

During the Republics first century, industrial development had moved so gradually that it was more evolution than revolution. At the beginning of its second century, the real revolution was in progressan increasing application of science to industry, the use of new energy sources for fuel and power, acceleration of transportation and communication, adoption of mass production techniques and the factory system, introduction of new agricultural machinery which would free millions of workers from the farms. Americans were undergoing an ordeal of social, economic, political and psychological change, a transformation of their environment that was as momentous as the discovery of the new continent some four hundred years earlier.

For many responsible citizens the nation appeared to be passing through a period of crisis, with indications of moral decay on every hand, growing corruption in government and business, and unemployment and poverty spreading throughout the land. To them the simple orderliness of the past held a greater attraction than the tumultuous uncertainties of present and future.

A generation earlier, Ralph Waldo Emerson had observed this natural tendency of men to turn away from change, and he rejected it. The world always had the same bankrupt look to foregoing ages as to us, he declared, as of a failed world just recollecting its old withered forces to begin again and try to do a little business. Only a decade earlier President Lincoln, caught in the awful vortex of the Civil War and faced with the necessity for swift changes, had warned that the dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present As our case is new so must we think anew and act anew. One of the great failings of mortals, however, is that even the wisest of them are never quite ready for the great social earthquakes of history that jar the human race into new courses.

Such an upheaval was occurring in the United States during the era following the Civil War, and the year of the great anniversary brought almost every aspect of that turbulent period into sharp focus. Because it was the Republics hundredth birthday, Americans were inclined to examine their past, to wonder about themselves and their institutions, and to seek an identity upon which to base their future.

It was a year of emotional, patriotic and religious revivals, of womens rebellions, of Indian wars and mythmaking in the Old West, of great frauds and betrayals. It was a year of intellectual cross-purposes, with more vitality in the sub-literature than in the mainstream of literature. It saw the early stirrings of a labor movement, and the shunting of the American Negro onto a long and roundabout road to freedom. It was the year of a Presidential contest in which the candidate who received the most votes lost the election.

In commemorating their past, Americans made the centennial year a matrix for their future, reflecting the faults and virtues of the mortal men who designed the pattern. Perhaps even those who envisioned a better design for the future would not have risked the venture. In his obscure way, Walt Whitman tried to express the uncertainty of all:

I myself but write one or two indicative words

for the future,

I but advance a moment only to wheel and hurry back

in the darkness.

Nevertheless, the Americans of 1876 were an energetic and exuberant people, filled with great expectations, confident that their nation would endure.

In our own stormy present, we too are setting a pattern for the future, and we may gain something from observing the follies and good works of our predecessors of a similar ageif it be only admiration for their unbounded hopefulness that some day all men would achieve such a sufficiency of freedom that they could live without fear.

It may be reassuring to the inheritors of their dream to note that countless orators gave thought to us, mentioning the year 1976 often in their speeches. None doubted that the bicentennial would arrive in good time, and that there would be Americans here to celebrate its coming.