YIELD

YIELD

Also by Anne Truitt

Daybook

Turn

Prospect

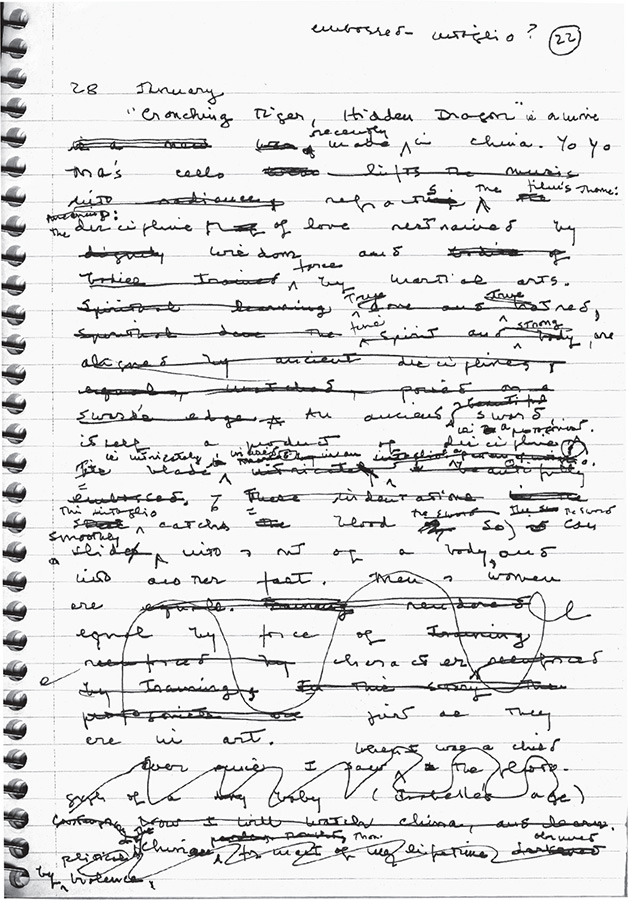

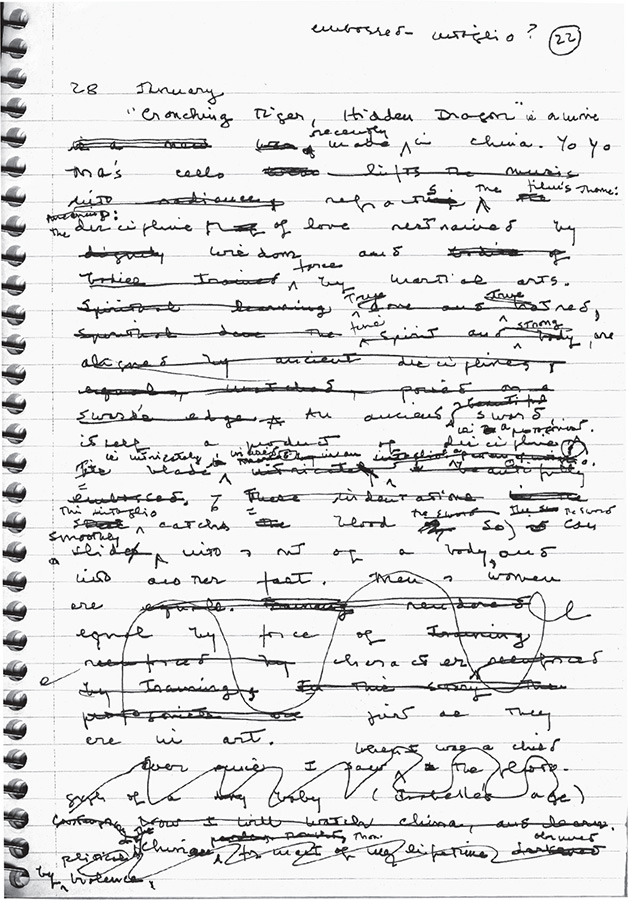

A page from Anne Truitts notebook, January 28, 2001

YIELD

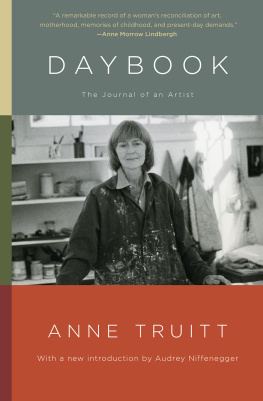

The Journal of an Artist

Anne Truitt

Foreword by | Edited by |

Rachel Kushner | Alexandra Truitt |

Copyright 2022 by Anne Truitt LLC.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Preface and Selected Chronology copyright 2022 Alexandra Truitt. Foreword copyright 2022 Rachel Kushner.

yalebooks.com/art

Designed by Katy Nelson for Joseph Logan Design

Set in Dover, designed by Robin Mientjes

Typeset by Katy Nelson

Printed in the United States by Sheridan

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021934203

ISBN 978-0-300-26040-3

eISBN 978-0-300-26432-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Jacket illustration: Anne Truitt, Sound Ten, 2003. Acrylic on paper, 19 19 in.

(50 50 cm). Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

Should I call this book a novel? It is something less, perhaps, and yet much more, the very essence of my life, with nothing extraneous added, as it developed through a long period of wretchedness. This book of mine has not been manufactured: it has been garnered.

Marcel Proust

Each individual lives the story of his or her own existencewe translate our lives as we live them. In my case translated into objects: art and books.

Anne Truitt

Alexandra Truitt

Rachel Kushner

Winter

WASHINGTON, DC

January 14, 2001

The validity of the world we find ourselves living in has its origin in the uniformity of our nervous and sensory systems, not in its intrinsic objectivity. Rather mechanicallylike ants or earth-wormswe act and react within a context we individually make up as we go. The coordinates of time and space, warp and woof, keep us in a general pattern of order. Yet minute differences in our physical setups make agreement essentially virtual, inexact, resulting inevitably in disorder on a scale from disquiet to war. And all is moving all the time, as if breathing.

I do not like to feel that I am making up as I go the world I live in. I would like to turn back to the world I have taken for granted until now. A solid world to which I could confidently try to adjust by practicing various ways of looking at it, coordinating its variety, by way of observation and logic. A world that offered me the hope that I might, if I made the effort, increase my understanding of it. Now, slowly and reluctantly, my mind, sadly, has dragged me to a point inside myself at which the world peters out into nothingness. Leaving me without perimeters or parameters, and forcing me to postulate that I am inventing what I live.

January 15

In two months and one day I will have lived on the earth for eighty years. The body that piled pillows prop up in bed on this misty still-dark morning is wicker. An animated arrangement of twigs, kept orderly and useful by respect and care. Orderly and useful and obedient to a conviction that I have not finished specific tasks that I seem to myself to have undertaken when I got born. Four sculptures are in the making in my studio. I intend to complete their undercoating within a week. I miss the vigor, the smooth sweet flow of muscular strength, the utter readiness with which I used to underwrite my will. Only two steps up on my ladder now, and only one ladder instead of three, and those two steps thought out in advance. I fear falling.

Lafcadio Hearn tells of the Buddhist priest Kbdaishi:

When he was in China, the name of a certain room in the palace of the Emperor having become effaced by time, the Emperor sent for him and bade him write the name anew.

Thereupon Kbdaishi took a brush in his right hand, and a brush in his left, and one brush between the toes of his left foot, and another between the toes of his right, and one in his mouth also; and with those five brushes, so holding them, he limned the characters upon the wall. And the characters were beautiful beyond any that had ever been seen in Chinasmooth-flowing as the ripples in the current of a river. And Kbdaishi then took a brush, and with it from a distance spattered drops of ink upon the wall; and the drops as they fell became transformed and turned into beautiful characters.

When I was living in Japan, I occasionally saw a Japanese conversation stop in midair until a character, apparently clarifying meaning, was quickly sketched on one conversants palm and looked at by the other.

This interchange had vigor and grace, immediacy, personality. No computer could replicate the particular movement. Something personal will be lost in the landscape of the computer, too vast and flat for this flavorful an event.

Art is above and beyond skill. A poetic truth. Skill takes an artist a certain distance, but it is only beyond skill that art springs forth. I like calling scientific concepts designated by certain specific interacting strokes of a brush a character.

An article in the New York Times tells of Li You, a twenty-three-year-old who lives in southern China, in Guanzi province, in rural Yangshuo. About six years ago he started using a computer, whereupon the Chinese characters he had learned to write in childhood began slipping away. The delicate strokes now scramble themselves and his pen falters in his hand. But then, he now almost never picks up a pen. A pity, a seepage of self-expression.

January 16

The meaning borne by a calligraphic character must lance instantaneously into the mind. A succinct message bearing at a glance the complexity of an idea in a delightfully compact package. A package made by hand too, the lan of that hand enlivening every stroke, personally inflecting the meaning of the whole.

I have stood transfixed by calligraphic scrolls inscribed by masters, understanding nothing and everything, save the power of the hand. The power of the hand is immediate. Had Jacques-Louis David not drawn Marie Antoinette sitting perfectly erect in the tumbril on her way to the guillotine, the once-elaborate flowered towers of her hair reduced to lank string hanging on either side of her mute face, we would not understand her so well. Nor him. Yet he had voted for her death.

January 17

An art historian commenting on an early Frank Stella: What he would like more than anything else is to paint like Velazquez. But what he knows is that that is an option that is not open to him. So he paints stripes. He wants to be Velazquez so he paints stripes. Attribution of motive always bothers me: any person attributing motive to another person has prepared a Procrustean bed and has the axe ready. I do not know what Frank Stella sees or feels when he looks at a Velazquez painting. I do not know that he would like more than anything else to paint like Velazquez.

I do know what I see in Las Meninas. I see the open door in the background without the figure in it. I feel in the very paint itself the rooms space: dusty, dark, and so immense that the people in it are rendered anecdotal. As, by implication, we human beings are incidental to the space and time into which we have been born.

Next page