The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

BY W. A. SESSIONS

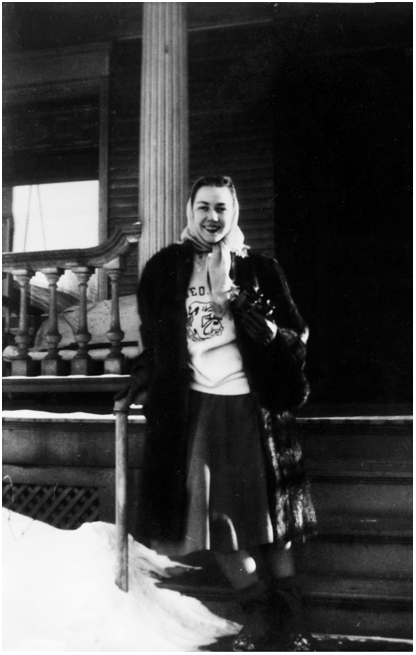

From January 1946 to September 1947, Flannery OConnor kept a journal that was, in essence, a series of prayers. She was not twenty-one years of age when she began this journal, and at twenty-two, when she wrote the last entry, it was clear that her prayer journal had already made a difference in her life.

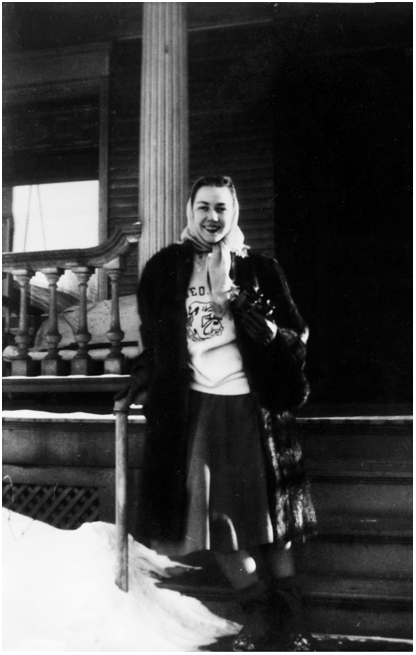

In this journal, written in Iowa City, where she had initially gone to study journalism but ended up in writing workshops, OConnor reckoned with her new life. Here, she consecrated herself to a force that had surrounded her, so she believed, since her birth, in Savannah, Georgia, on March 25, 1925. Iowa City, in the American heartland, seemed the polar opposite of the racially mixed but segregated port city, which in her time was exotic (the last great port southward, before Cuba and the Caribbean). For her, Savannah had opened up more than the diversity of human existence. There a series of Catholic rituals and teachings had offered her young life a coherent universe. By 1946, Savannah had for OConnor ceded to the university world of Iowa, where new influences, including intellectual joys, brought with them questions and skepticism.

In that freedom, OConnor began her journal and initiated a rare colloquy. She began to compose entries that soon transcended simple meditations on the perplexities of life. From the start (we do not have the first pages) the journal contained lyric outcries that became a singular dialogue. In fact, she seemed to be inventing her own prayer form. Abrupt, truncated, and serial, the individual entries convey great intensity: Oh Lord, she cries out toward the end of the journal, make me a mystic, immediately. This urgency was present even in her final cry of disappointment. By then she knew that she would not have an immediate answer from the object of her loveat least not on her own terms. She would have to wait patiently in a world of triviality, and even of the erotic, until the Lords responses came.

Such journal entries were not as spontaneous as they might seem. Even at twenty-one, OConnor was a craftswoman of the first order, and the facsimile that appears in this volume reveals her careful emendations. To dramatize her desireand she was foremost a dramatic writershe recognized that she must not report, but render, in the Jamesian manner she was learning at Iowa. Her letters of action, written in search of her lover, became entries in a journal. The entries themselves could be simple, intimate, at moments childlike. At the same time, they could dramatize desires that were Olympian, astonishing for their range and depth of observation about human life and destinyand perhaps too astonishing for earlier readers and guardians of the sheaf of handwritten pages buried for more than half a century.

But to whom did she write these letters, these entries? Who was this lover she identified as such? In the journal, she generally named this presence God. She called him Father only in connection with a Gospel quotation, and she made only a few direct references in the whole journal to Christthe most direct an impassioned petition: I dont want to be doomed to mediocrity in my feeling for Christ. I want to feel. I want to love. Take me, dear Lord, and set me in the direction I am to go. Her love was universal and, like Mosess burning bush, alive and on fire.

In fact, if her love represented an absolute, the writer herself existed, as OConnors allusions in her journal emphasize, in a real, deeply human world. God and humanity were not mutually exclusive terms, of course, and the young writer understood her daily world as a particular moment in history, its center always in that lover she felt seeking her as she sought him in the midst of a bustling Iowa City in the latter part of the 1940s. GIs were returning from war for their free education, and the streets were packed with students. Remarkably, for OConnor, even African Americans were there without apparent social restrictions. One of her closer creative-writing friends, a young woman, Gloria Bremerwell, with whom she had dinner many times, was African American. OConnor may not have known that there were no barbershops in Iowa City where black males could get their hair cut at the time.

The prayers in her journal naturally emerged out of the busy classrooms, libraries, and streets of Iowa City. Her dorm room, which opened onto the only bathroom on the floor, was far from private. In that awkward room the young writer began her journal as she sat at a desk with her pens, pencils, and typewriter beside her hot plate (all the refrigerated items stood outside the window). Thus her world was far from cloistered. Yet in her years at Iowa she was increasingly seeing openings both out of and into her lifeand her desire to write fiction carried the greatest meaning for her in such a setting, where so many influences converged.

In fact, in the midst of writing these prayers, she began her first novel, eventually titled Wise Blood. That was during the Thanksgiving break of 1946, and whatever else the outreach of prayer had done, in initiating this truly original work of American fiction, OConnor had extended the reach of her journal. Her prayer to be a good writerreiterated often in the journalhad already been answered. She had discovered within herself a deeper source for acts of her imagination. Indeed, she had learned there in Iowa how Coleridges act of imagination as the willing suspension of disbelief could become for her the freedom of creating fiction in that suspension.

By the time OConnor wrote her final journal entry, she had offered herself directly to God. In her entries she sought to consecrate herself so that she might love the absolute more, sacrifice more. But on September 26, 1947, three years before the sudden arrival of lupus, the disease that had killed her father and would kill her, the young OConnor wrote her last entry. Nothing appeared to have happened. On that day her thoughts are so far away from God, and she wondered in a discordant image if the feeling I egg up writing here was little more than a sham. That very day, in fact, she had proved herself a gluttonfor Scotch oatmeal cookies and erotic thought. She closed the journal matter-of-factly: There is nothing left to say of me.

Actually there was a great deal left. The journal itself was finished, and it accurately reflected OConnors literary achievements thus far and even foretold her suffering and death. Not least were the results of her outlandish hope, at least in the twentieth century, for total commitment to God. In that hope she had created characters who knew (negatively, like the Misfit of A Good Man Is Hard to Find, or positively, like the tattooed man of Parkers Back or Ruby Turpin of Revelation) the cost of having a destiny painful to wait out but, in her fiction, alive only through their waiting.

Before Christmas of 1950, OConnor traveled alone by train from Connecticut to Georgia. Her friend Sally Fitzgerald saw the active young woman with a bright beret off at the station. But by the time OConnor arrived in Atlanta, she looked drawn and bent, like an old man, according to her waiting uncle. In the course of her journey from North to South, OConnor had had her first attack of lupus, the disease that afflicted her until her death in 1964, at age thirty-nine. Paradoxically, those years of suffering became the most fertile for her writing, and she produced some of the greatest fiction in American literature. Ironically, the prayers of her journal had been answered.