THE TERRIBLE

SPEED OF MERCY

2012 by Jonathan Rogers

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a registered trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Published in association with Eames Literary Services, LLC, Nashville, Tennessee.

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Excerpts from The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery OConnor by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. All rights reserved. Used with Permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rogers, Jonathan, 1969-

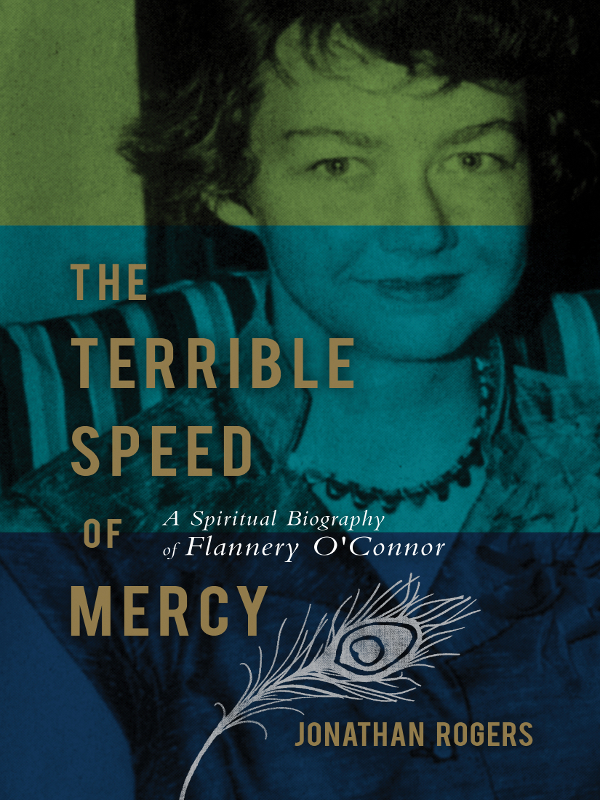

The terrible speed of mercy : a spiritual biography of Flannery OConnor / Jonathan Rogers.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59555-023-1

1. OConnor, Flannery. 2. Authors, American--20th century--Biography. I. Title.

PS3565.C57Z853 2012

813.54--dc23

[B]

2011052998

Printed in the United States of America

12 13 14 15 16 QG 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Andrew Peterson

and the rest of the Rabbit Room community

PUBLISHERS NOTE

A highly offensive racial slur occurs some thirteen times throughout this book, in each case quoted from Flannery OConnors fiction or correspondence. The publishing team discussed at some length how best to handle this word in light of the sensibilities of twenty-first century readers. In the end, we decided to let the word stand in its full offensiveness, on the grounds that the repugnance the reader feels at the word is a key reason OConnor used it in the first place. It may be true that there was more open racism in the 1950s and 1960s than in the twentyfirst century, but that hardly explains why OConnor used the n-word in the thirteen instances quoted in this book. A reader of literary fiction in the 1950s would be no less offended by the word than a reader of literary fiction in 2012. To expurgate OConnors language would be to suggest that we understand its offensiveness better than she does, or perhaps to suggest that the readers of this book are more easily offended than OConnors original audience. We have no reason to believe that either is true. So we leave OConnors language intact, and we leave you with this warning: you may find some of the language in this book offensive; that is as it should be.

CONTENTS

Flannery OConnor was twenty-seven years old when her debut novel Wise Blood was published. She was small of frame and sweet-faced in spite of the fact that she had already lived for two years with lupus. She was mostly quiet in public, but when she did speak she spoke in the lilting tones of Georgias Piedmont. She did not, in short, come across as a force to be reckoned with.

While visiting friends in Nashville, OConnor encountered a man who put into words what many of the people who met her must have been thinking about the young author of Wise Blood. That was a profound book, he said. You dont look like you wrote it.

OConnor described the scene in a letter to Elizabeth and Robert Lowell. She wrote, I mustered up my squintiest expression and snarled, Well I did.

She did indeed. She who lived a comfortable, conventional, pious middle-class existence on a dairy farm in Milledgeville, Georgia, wrote stories that are like literary thunderstorms, turning on sudden violence and flashes of revelation that crash down from the heavens, destroying even as they illuminate.

Nothing about OConnors outward demeanor would suggest that such storms surged within her. Hers was a quiet lifenot free from trouble by any means, but regular and stable. Except for five and a half years in her early twentiesyears spent training as a writer in Iowa, New York, and Connecticutshe spent her whole life in Georgia, under her mothers roof. Her mother could be domineering, but she was solicitous of Flannerys health and well-being, and she always gave her daughter the space to do her work, even if she didnt always appreciate the work she was doing.

Flannery OConnor and her mother lived a most regulated, most devout life on the farm they called Andalusia. They rose every morning for six oclock prayers, then rode together to Sacred Heart Catholic Church for seven oclock Mass. They sat in the same pew every day.

After Mass, the OConnor women returned to the farmhouse, and Flannery sat down at the typewriter in the front room that used to be the parlor. Thereevery morning including Sundaysshe spent four hours writing stories about street preachers, prostitutes, juvenile delinquents, backwater prophets, hardscrabble farmers, sideshow freaks, murderers, charlatans, and amputees while her mother tended to the business of the house and farm.

Then, at noon, the OConnor women drove back into town, where they had lunch at the Sanford House tearoom among the hatted and white-gloved ladies of Milledgevilles patrician class. Flannery was especially fond, according to biographer Brad Gooch, of the fried shrimp at Sanford House and the peppermint chiffon pie.

No, Flannery OConnor didnt look like she could have written Wise Blood or The Violent Bear It Away or A Good Man Is Her life wasnt as uneventful as all that. Scholars including Jean Cash, Paul Elie, and Brad Gooch have demonstrated that her life did indeed provide the raw material for a fascinating biography. It is true, however, that her life was mostly free of the drama and self-indulgence and entanglements that often make for more exciting copy in her peers biographies. There were no blowups or meltdowns or crack-ups or addictions in Flannery OConnors life. There was mostly a quiet attention to the work at hand.

Flannery OConnor wrote of the great mysteries. She wrote in the great mysteries and was a mystery herself. In The Life You Save May Be Your Own, Mr. Shiftlet speaks to the mysteries of the human heart in his first meeting with Lucynell Crater.

Lady, he said, and turned and gave her his full attention, lemme tell you something. Theres one of them doctors in Atlanta thats taken a knife and cut the human heartthe human heart, he repeated, leaning forward, out of a mans chest and held it in his hand, and he held his hand out, palm up, as if it were slightly weighted with the human heart, and studied it like it was a day-old chicken, and lady, he said, allowing a long significant pause in which his head slid forward and his clay-colored eyes brightened, he dont know no more about it than you or me.

Thats right, the old woman said.

Why, if he was to take that knife and cut into every corner of it, he still wouldnt know no more about it than you or me. What you want to bet?

Nothing, the old woman said wisely.

The biographer of Flannery OConnor is in the same fix as that doctor in Atlanta. No amount of poking around in the external events and facts of her life is going to get at the heart of her. Theres no accounting for Flannery OConnor in those terms. Thankfully we have her letters, which provide windows into an inner life where whole worlds orbited and collided.

The outward constraints that OConnor accepted and ultimately cultivated made room for an interior world as spacious and various as the heavens themselves. Her natural curiosity was harnessed and directed by an astonishing intellectual and spiritual rigor. She read voraciously, from the ancients to contemporary Catholic theologians to periodicals to novels. She once referred to herself as a hillbilly Thomist. She was joking, but the phrase turns out to be helpful. The raw material of her fiction was the lowest common denominator of American culture, but the sensibility that shaped the hillbilly raw material into art shared more in common with Thomas Aquinas and the other great minds of the Catholic tradition than with any practitioner of American letters, high or low.

Next page