Introduction

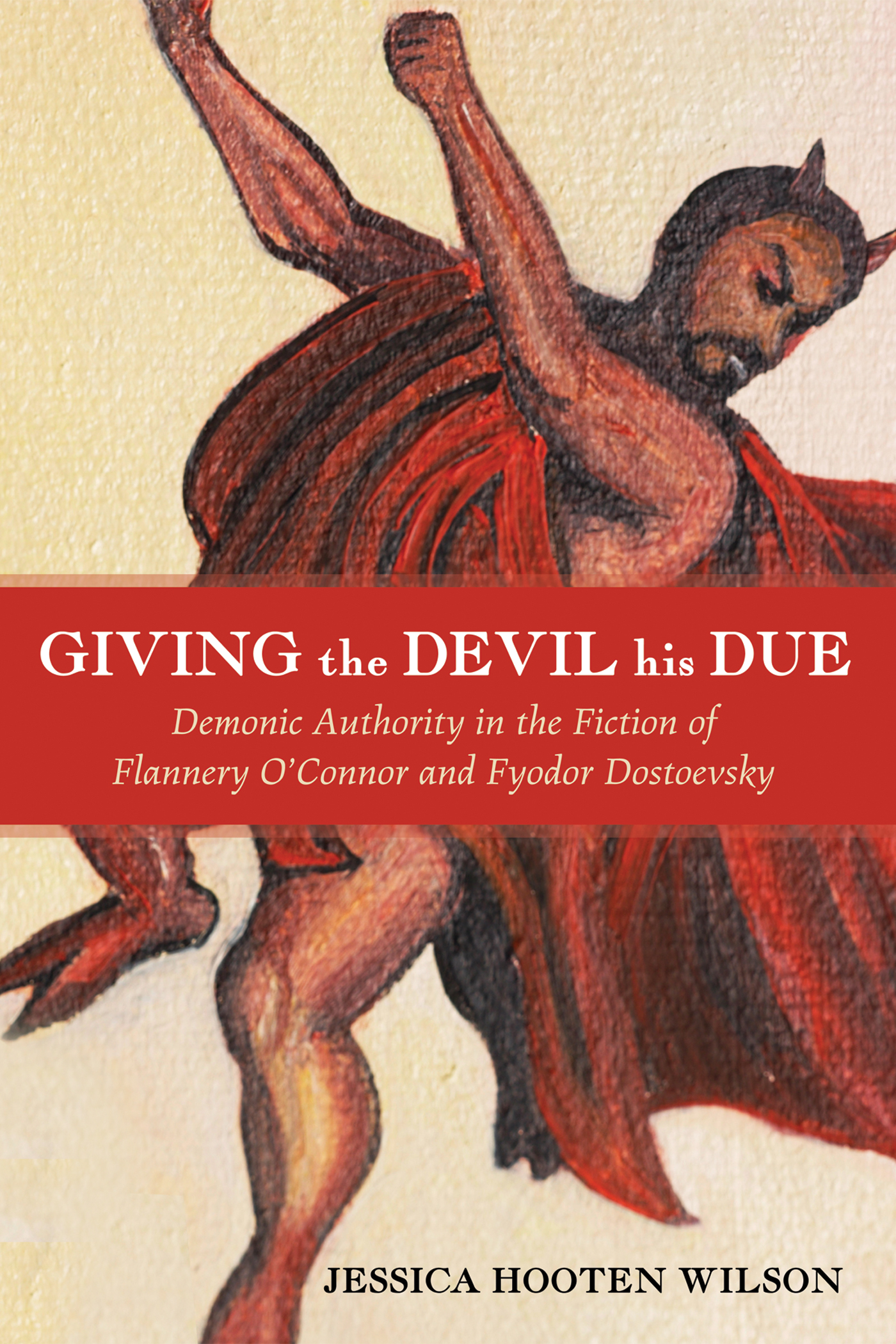

A t the mere mention of Flannery OConnor and Fyodor Dostoevsky, some people experience distaste, revulsion, or horror. People accuse the writers of being dark, violent, and even misanthropic. As a scholar of these two authors, I often hear remarks such as, Ick, OConnorall those dead bodies, or, You smile too much to be a Dostoevsky scholar. On the other hand, the readers who love these two authors often deem them to be saints, elevate their works to the status of near-biblical revelation, make pilgrimages to their grave sites, and display memorabilia on office walls and computer screens. Both OConnor and Dostoevsky may have expected their audiences aversion, but they would have been ill at ease with the adulation. After all, they set out to expose the comfortable lies that had been digested by their generations and to replace these lies with ancient truths from Christian Scripture. Those who attempt to imitate Christ should expect the world to hate them for it.

Although from different sects of the church, both were passionately devoted Christians: OConnor was a cradle-born Roman Catholic, and Dostoevsky was Russian Orthodox, and became more devout following a conversion in prison. While the rest of the world was becoming progressively secular, these two remained loyal to their faiths and considered their art to be their vocation. Neither succumbed to the popular accommodation of church doctrine, as will be shown lateralthough Dostoevsky was swayed for a brief period of his life by Christian Socialism, only to turn degrees from it. And, it is the faith of these two writers that undergirds not only their aesthetic visions but also their themes and ideas. The way in which these two writers set about putting their faith into fiction has been discussed ad nauseum by many scholars, but I want to look more closely at how their faith led them to unveil a modern deceptionthat of the autonomous self.

To elucidate their common revelations, I turn to the work of Ren Girard, who first discovered the lie of the autonomous self when reading Dostoevsky. Originally a French literary scholar, Girard branched into cultural criticism in 1961 when he published his first book Deceit, Desire and the Novel , an examination of five novelists, including Dostoevsky. Girard uncovered the nature of conversion in the novelists work. For Girard, the romantic lie bought and sold by most modern novelists is that of the autonomous self whereas the novelistic truth unveiled by great literature is the opposite, the mimetic nature of each human being.

In Ren Girard and Secular Modernity , Scott Cowdell gives a brief but accurate description of secular modernity in the Western world that shows how religions hold on society disintegrated from the late Middle Ages until now. His accounts attempt to pull together the narratives put forward by thinkers such as Richard Dawkins and, on the other end of the spectrum, by Charles Taylor. While versions of the story emphasize alternately the developments in science, or changes in economic structures, or moves in government towards democratization, most seem to recognize secularization as the increase in personal autonomy accompanied by a variety of alternative metanarratives from the Judeo-Christian one. This world in which God is not the authority for society, nor the Alpha and Omega for individual persons, is labeled secular. However, Cowdell offers a caveat via Girard. In Girards theory, the greater autonomy of the modern self is an illusion. Girard sees secular modernity in the West as functionally religious, Cowdell notes, though its religion is based on a sovereign self versus a divine authority.

Girards theory has developed and evolved since 1961 and been extended into numerous other arenas of the academy (which this book will not delve into). For my purposes, I will look at his discoveries as they pertain to literature, mostly to those found in Dostoevsky that may be extracted and applied to OConnor. As previously stated, in summary, Girard asserts that all human beings imitate the desires of others, whether or not they acknowledge the imitation. Behind his theory are theological assumptions based on Judeo-Christian Scriptures. Girard clarifies these suppositions in a handful of his works, including The Scapegoat , I See Satan Fall Like Lightning , and Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World . Rather than quote extensively from numerous sources, I will delineate his assertions here. According to Girard, because God created humans in his image, a model exists from the beginning that we can embrace or deny. In biblical accounts, one of Gods angels, Lucifer, denied the authority of God, denied being a creature and considered himself an autonomous individual. Satan, as he became known, established himself as an alternative model. When the Son of God renounced his high place in the Trinity to appear historically on earth as Jesus Christ, he countered this modelnot with a showcase of power but with humility by becoming a victim to the violence of those who followed Satan. Thus, the choice of whether to follow Christ or Satan is also whether to be humble or proud, whether to be truthful or blind, and whether to suffer or cause violence.

The same choice that Girard is convinced lies before human beings, whether to imitate Christ or Satan, underlies all of OConnors and Dostoevskys respective works. In Dostoevsky, his character Ivan Karamazov famously reduces the choice when he says, Without God, all is permissible. One watches as the notorious Ivan, who has accepted his own premise, is driven mad by the devil on his shoulder. In OConnor, The Misfit in A Good Man is Hard to Find echoes the choice with Girardian language: If [Jesus] did what He said then its nothing for you to do but... follow him , and if He didnt then its nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best you canby killing somebody . Such a choice sits uncomfortably with the readers of OConnor and Dostoevsky who want to inhabit a middle ground.

OConnor and Dostoevsky scandalize the modern reader by portraying this unwanted truth to readers. The either/or choice outlined by Girard and presented by these authors does not allow for the possibility that someone could be a good person without following Jesus Christ, or could be an autonomous individual who also believes in Jesus as God. When Ivan decries the terms of Gods harmony and returns his ticket, he becomes not only possessed by a devil but also complicit in his fathers murder. In OConnors novels, Hazel Motes denounces Jesus as a liar to found the Church without Christ, and then he justifies the homicide of Solace Layfield with his own moral system. Similarly, in OConnors second novel, after Rayber asserts that religion is insubstantial propaganda used to control and restrain a persons natural and good intuitions, he finds himself unable to validate his son Bishops existence and later becomes complicit in filicide. In Dostoevsky and OConnors fiction, the Christian life is not one option among many; rather, it is the only alternative to violence.

The truth that Girard discovers in Dostoevsky is the same truth that OConnor propagates in her fiction. Few critics have examined her work in this light. In 2007 Susan Srigley relied on Girard to take readers beneath the surface of OConnors scandalous fiction to understand the source of violence and the possibility of self-sacrifice as a way to bear it.