Emperor of the Earth

Czeslaw Milosz

University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England First Paperback Edition 1981 ISBN 0-520-04503-3

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-20005 Copyright 1977 by The Regents of the University of California Printed in the United States of America

Preface

"We are now like the Dalmatians in the collapsing Roman Empire. They cared when the others wouldn't give a damn." This is how a friend of mine from Poland spoke of the difference between the so-called Eastern and Western Europeans. He might have added that although we have been attracted to the great Western European centers of learning and art for generations, our admiration has never been without reserve. Yet it is true, something new has taken place in the last decades. Changed into outsiders by the political division of Europe, we began to see more clearly than before that which Western man, submerged by everyday life, has been reluctant to admit, and the spectacle appearing before our eyes did not seem very promising. In my friend's mixture of scorn and regret, regret prevailed. He would say that even if the only civilization that made possible the conquest of the planet by modern science has entered the stage of spiritual decline, this should still not be interpreted as auguring the emergence of a new civilization able to replace it. At best the vital tasks have to be taken over by the peripheries, by less illustrious nations, simply because the others have grown slack.

This conversation is well suited to introducing a collection of essays on subjects taken mostly from Slavic literatures. It is not difficult to detect in my friend's views the residue of an old love-hate relationship between the rural and industrial areas of Europe, as well as an echo of the accusations leveled by the

Slavs at the materialistic West for at least a hundred and fifty years. And yet, in the new context of this last quarter of the twentieth century, the possibility of a shift from the center to the peripheries cannot be dismissed lightly. I must abstain from conjectures, for I cannot pretend to be an impartial judge. Divergences of opinion on particular points do not make me very different from my colleagues in Poland, Czechoslovakia, or Lithuania. Even if I am skeptical of the generalizations typical of any philosophy of history, I recognize something specific in both our common heritage and our present attitudes.

Why such a concern with man's destiny, why such an obsession with the riddle of Evil active in History? Whatever the answer, most of the following pages are dedicated to authors who passionately believed that they were called to influence the future, be it through Cassandra-like warnings regarded, it seems, as a kind of magical counteraction. Intensity may easily lead to delusion, and as is often the case, intensity coupled with pessimism may result in odd ideas. Nevertheless, it is energy, and as Blake says, "Energy is Eternal Delight."

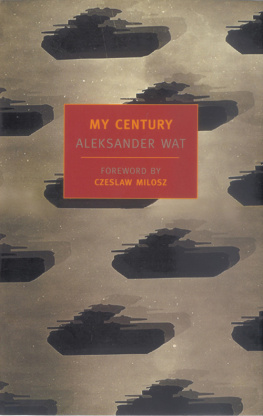

As to the composition of this book: I did not try to be scholarly where I was tempted to be personal, and traces of my wanderings through various lands and several languages and literatures are noticeable. I begin with a true story, "Brognart," where I describe facts that came to my attention when I lived in France. This story, a confession of remorse, gives a glimpse at the fate of countries situated between Germany and Russia, but in reality tells of my (our) conflict with French intellectuals. The essay on Vladimir Solovyov, "Science Fiction and the Coming of the Antichrist," was inspired by the memory of a fresco by Luca Signorelli in the cathedral of Orvieto. The piece on Stani-slaw Ignacy Witkiewiczan apocalyptic visionarylinks my student years in the thirties, when he fascinated me, with the present day. "Krasiriski's Retreat," another return to my student readings, attempts to determine how a Polish romantic poet could write in 1833 (at the age of twenty-one) a drama on the approaching world revolution. "On Pasternak Soberly" is a polemic, not unrelated to my practice as a poet, with certain poetics of our century represented perfectly by the oeuvre of this Russian poet. "On Modern Russian Literature and the West" raises the old issue of two radically opposed perspectives. "The Importance of Simone Weil" is a tribute to a thinker who pushed to an extreme her disagreement with "the world" and the powers that rule over it. "Shestov, or the Purity of Despair" is about a great Russian philosopher akin to Simone Weil in his refusal to assuage the unbearable character of human existence with vain consolations; the essay also recalls a desperate young woman in Paris who took great comfort in his books. "Dos-toevsky and Swedenborg" is the outcome of reflections on the great Swede who has been maligned and often treated as a madmanthough not by Dostoevsky. The name in the next title, "On Thomas Mayne Reid," says nothing to the public: I relate who he was, how I discovered him in my childhood, and why he is known in Slavic countries. "Joseph Conrad's Father" sketches the biography of a poet and revolutionary. "Eastern Europe" is a vague term because we repeatedly encounter a conflict between the Russians on one hand and the remaining nationalities on the other, but the nearly exemplary life of this nineteenth-century Polish romantic should give insight into these tensions. Moreover, it throws some light upon the fate of the hero of the last chapter, "A One-Man Army: Stanislaw Brzozowski." This philosopher was a major influence in my youth and is still at the center of intellectual controversies in Poland. In turn a Nietzschean, a Marxist revisionist, a self-avowed disciple of Giambattista Vico and Cardinal Newman, his spiritual itinerary is expressive not only of his own time but of ours as well.

Some sections of the present volume were written in English and some in Polish, the latter being translated by myself or others. I wish to thank those students who occasionally helped in giving final shape to my own versions, as well as my colleague professor Francis J. Whitfield for his attentive reading of the manuscript and very valuable suggestions.

Acknowledgments are due to the following magazines where the texts first appeared: to Kultura, Paris, for "Brognart"; Dissent for "Science Fiction and the Coming of the Antichrist"; Tri-Quarterly for the essays on Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz and Lev Shestov; Books Abroad for the essay on Boris Pasternak; California Slavic Studies for "On Modern Russian Literature and the West" and the first part of my study on Brzozowski; The Slavic Review for "Dostoevsky and Swedenborg"; and to Kultura and Mosaic for "Joseph Conrad's Father."

C.M.

Brognart: A Story Told Over a Drink

Once quite a while ago in the fifties, I found myself in Marles-les-Mines, a small town in Pas-de-Calais, a black coal-mining region. A wet winter. In the fields the dazzling green of winter wheat, inky waste heaps and movement in the air: the turning gears of the lifts. It rained almost incessantly in Maries; walls blighted with dampness, mud between pavement stones, skeleton trees. The first passerby I asked for directions, a miner with skin tattooed by coal dust who was returning from work carrying a lantern, answered in the language in which I addressed him. I have a sharp eye, he was a Pole; probably half the people in Maries understood Polish. The hue of light there is murky, foggy, and whenever the door of a cafe was opened, a gust of steam burst forth (maybe I'm unfair in transferring the smoke and the steam to the light there in general). There were bikes in front of the tiny cafes and inside, over shots of calvados, everyone was talking about Brognart. And there in Maries, the matter gripped and moved me.