Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my cousin Michael McDonnell who, during my visit to his then home in Kiltimagh in the spring of 2006, whetted my appetite for this story as we talked about family history. My thanks to the Franciscan community for facilitating access to the manuscripts of my great granduncle, Brother Paul Carney.

This project would not have seen the light of day if I hadnt participated in the MA (Writing) Programme at NUI Galway (20072008), where I was greatly encouraged by Professor Adrian Frazier, Dr John Kenny and Dr Patrick Lonergan, as well as by my fellow writing students.

I am thankful for the resources of the following libraries: Achill branch library (Pauline Quinn); Castlebar County Library (Ivor Hamrock); the Hardiman Library, NUI Galway (Marie Boran and Kieran Hoare);National Folklore Collection, University College Dublin; National Library of Ireland; Trinity College Library; Representative Church Body Library, Dublin. I was able to draw on the resources of the Berg Room, New York Public Library, and the Brooklyn Historical Society Library, while on a visit to the USA in September 2009.

I was privileged to spend time at the Heinrich Bll cottage in the shadows of Achills Slievemore in January 2009 while researching this book. I am grateful to John McHugh and to the Heinrich Bll Foundation for the residency, and also for the opportunity to present at the Heinrich Bll Weekend in May 2009. John OShea, Dooagh, was a mine of information on Achill, as was Pat Gallagher of the Valley House who responded to my numerous queries. I appreciate the valuable information received from relatives of Agnes and Randal MacDonnell and Irene Elliot: Jim and Marilyn Rankin, Ann and Richard MacDonnell and Randal MacDonnell.

It was helpful to have aspects of the research for this story published in a number of journals and magazines and I am grateful to the following publications and editors: the Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society (Dr Diarmuid Cearbhaill); Cathair na Mart Journal of the Westport Historical Society (Aiden Clarke); Verbal Magazine (Catherine McGrotty); The Irish Story (Eoin Purcell). I was also encouraged at being included among the prize winners in the Unbound Press (UK) competition for opening nonfiction chapters in 2010, and for inclusion in their anthology.

For their assistance with images and illustrations for the book, I am grateful to Glenn Dunne and Berni Metcalfe of the National Library of Ireland; Tom Kennedy, on behalf of the Wynne Collection; Isaac Gewirtz and Tom Lisanti of the Berg Collection, New York Public Library; Ivor Hamrock, Mayo County Library; Ann & Richard MacDonnell, UK; Michael McDonnell, Galway; and The Mayo News archives.

I appreciate the support of my siblings, Kathleen, Noreen and Paddy. On a sunny St Patricks Day in 2009 my brother, Paddy Murphy, and I visited a number of places associated with Brother Paul Carney around Ballyhaunis, County Mayo, including his birthplace in Ballindrehid, the site of the former Granlahan Monastery, and the graveyard of the Augustinian Friary, Ballyhaunis, where the monks parents (my great great grandparents) are buried.

I would like to thank Kathleen Thorne, David Rice and my fellow writers from the Killaloe Hedge School Writer Group for their constant support, and especially Ciarn Grofa for his detailed and perceptive comments on the draft manuscript. I am also grateful to my fellow book club readers in The Kyleglass Book Worms who have taught me much about reading and writing, and to Margaret Enright for reading the manuscript. Many friends in The Duck Walkers and Gawbatas listened patiently to accounts of my writing progess while rambling the hills and walking trails of Limerick, Clare and Tippeary.

Thanks to The Collins Press for accepting my manuscript for publication and for their work in getting this story into print. Thanks also to Isobel Creed, Vanessa OLoughlin and Patricia OReilly for their professional inputs.

Finally, thanks to Mick, my best reader, for his love and encouragement.

PROLOGUE

Achill

Summer 1888

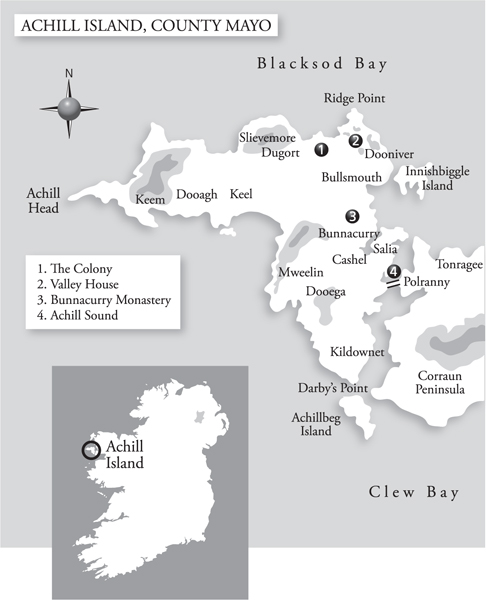

A gnes MacDonnell is exhausted. She has travelled by rail across England from her London home at Belsize Square, from Holyhead by steamer to Kingstown, and then the final leg of her journey across the breadth of Ireland on the Midland Great Western Railway train to Westport. She crosses the bridge to Achill Island to the rattle of car wheels and the clip clop of horse hooves, her body jerking from side to side with the movement. The glint of new steel on the railings reminds her of the city she has left behind. Had she travelled to the island a year earlier while the swivel bridge was under construction, the car would have had to wait until low tide to pass through the channel at the village of Achill Sound. It is just ten more miles to her new home at the Valley House in Achills northwest corner. There she will rest, replenish her energies, and tackle the challenges of the 2,000 acre estate she now owns.

Many travellers before her have come to this remote place. They followed the same approach road that swings in an arc around the south shores of Blacksod Bay. Four miles out from Achill, on turning the bend of Tonragee, the visitor faces the spectacle of Slievemore Mountain, mottled with shadows like patches on a piebald horse. The mountain overpowers the island and it is as if it wraps within its entrails the dramas that unfolded beneath its shade. The travellers to Achill in the previous half-century were many and varied: proselytisers imbued with a zeal to convert souls; independent Victorian women who wrote of famine horrors; men who hunted for red-brown grouse on mountain slopes; artists, mesmerised by the islands shifting light, who set up their easels at the Atlantics edge; seekers of the amethysts purple glow at the quartz quarry in Keem.

From Achill Sound the horse gallops along the islands spine road as far as Bunnacurry, where the tower of the Franciscan monastery juts into the sky. The car veers north through a treeless landscape where an expanse of bog stretches away as far as Agnes can see. Women in scarlet petticoats walk at the roadside in single file, bent beneath creels of turf and seaweed like beasts of burden. Children in bare feet shout and scamper after the car. Old men suck clay pipes and stare at her from the dark doorways of cottages. Agnes may not have yet observed how few young people there are on the island, many of them having made the annual migrant journey to the harvest-fields of Scotland and England. Everywhere, there is the smell of peat-smoke that oozes and circles languorously into the island skies.