Acknowledgements

Hyekyoung Ahn: for talismans and continual cultural guidance.

Hind Baki: for encouragement to write only what feels right.

Kyu-tae Cho: for gifting my grandfathers legacy.

Youngsoon Choi and Eunjun Kim: for meals, art and language lessons.

Dahlia Gerstenhaber: for sharing a mutual passion for the haenyeo.

Youngsook Han: for finding our property, liaising with our contractor, and being by my side at any hour.w

Mikyoung Kang: for honoring us in our home during Chuseok season.

Shinhwan Kang: for constant care and attention while we lived in Gwideok.

Kyounghee Kang and Keun Lee: for loving nurturance and practical and aesthetic construction advice.

Jong-ho Kim: for sharing Aewol history.

Seungeun Kim and Jee-eun Lee: for their island enthusiasm and our food club adventures

Soonjin Kim: for her green thumb in our garden.

Father Patrick McGlinchey: for recollections of Hallim Handweavers.

Sister Rosarii McTigue: for her spiritual and resilient character.

Kyeungsook Min: for tender house-sitting during the summer of 2017.

Jung-hwan Moon: for managing construction of our house with care, patience, taste, and humor.

Jolena Pamilar: for a most memorable summer together and house moving assistance.

Giuseppe Rositano: for insights on shamanism and Jeju culture.

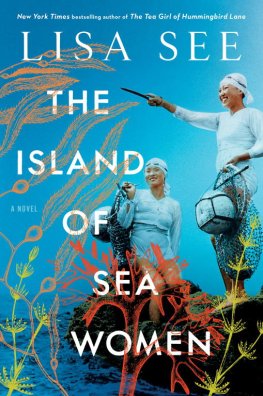

Lisa See: for writers inspiration and a shared moment together in Jeju

Thu Kim Vu: for creative listening and post-manuscript R&R in Taiwan.

Soonja Yang: for urging me to write before its too late and for introducing me to her native island and world of textiles.

Kwangsook Yim: for being my sidekick and companion in the sea.

Hank Kim and Misoon Yang, my publisher and his wife, for their steadfast faith in my projects and encouragement to discover my truths.

Eugene Kim, my editor, for her insightful comments and broader perspective that kept me on track. And Todd Thacker for his meticulous copyediting eye.

There are also thosenear and farwho knew of this project and supported me continuously with their love. Thank you. You know who you are.

Jan, my life partner: for keeping our marriage as improvisational as jazz. And David, our son: for adding syncopation.

Additional Photo Credits

Robert Koehler

Song Myongjoon

Image Today

About the Author

Brenda Paik Sunoo

Brenda Paik Sunoo is a third-generation Korean-American writer and photojournalist based in Jeju Island, South Korea. Born and raised in Los Angeles, California, she graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles, with a Bachelors Degree in sociology and received a Masters of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from Antioch University. Before becoming a photojournalist, she worked as a reporter for The Orange County Register and served as news editor for the English edition of The Korea Times (Hanguk Ilbo).

In 20072009, she spent a total of seven months conducting research on Jeju Islands aging free divers, known as haenyeo. This project resulted in her book Moon TidesJeju Island Grannies of the Sea (2011), which contributed to the successful campaign for UNESCO designation of the haenyeo as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Shes also written two previous books: Seaweed and ShamansInheriting the Gifts of Grief and Vietnam Moment. When she is not writing or taking photos, she pursues her passion for mixed media art.

www.brendasunoo.com

MOON TIDES

Jeju Island Grannies of the Sea

Written by Brenda Paik Sunoo

Interpreted and Translated by Youngsook Han

240 pagesUS$ 65.00 / 42,000 wonHardcover

For centuries, Jeju Islands sea women have faced the tempestuous tides of history and struggle for survival. Their intimate relationship to the land and sea, their shamanist beliefs, and their communal village life have protected them throughout their lives. However, Jeju Islands haenyeo are a dying breedperhaps the last of their generation. Their numbers have dwindled from 15,000 in the 1970s to approximately 5,600 in recent decades. This is the first book by an American journalist to document the lives of these rare divers through intimate interviews and photographs. Their stories will appeal to those desiring a life of purposeundulating and infinite as the sea.

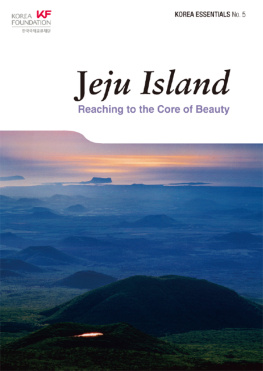

Aewol, Moon by the Water

I pinch myself whenever I look at a map of Jeju Island. The mainland peninsula of Koreabordered by China to the northwest and Russia to the northeastappears as a westward-facing tiger. Below it, Jeju Island floats in the Yellow Sea like an Easter egg. By choice, the scope of my life has shrunk from ultra-large to extra-petite when my husband and I bought a dilapidated stone house in Aewol, a traditional fishing port village on the northwest coast of Jeju Island.

We didnt intend to buy land, nor build a house. Our original idea was to search for a large two-bedroom apartment with a sea view. But when our friendsnatives of Jejuviewed our options, they wondered: Why do you need to move so close to the sea? The sea is all around you. If you live too close, your car will rust. Your windows will be blasted by strong typhoons, and your bones will ache from constant damp weather. Move inland.

Their well-heeded warnings led us to seriously consider what type of residence would be appropriate. What kind of social and cultural environment did we want to inhabit? We could see construction popping up everywhere: new pensions, apartment buildings, cafs, office structures, restaurants. Foreign investorsgiven permanent residency incentiveswere buying land in the mid-mountain areas, creating new colonies of suburban-style homes. Most building projects were being designed in a Western style, changing the indigenous architectural landscape of Jeju Island. Younger mainlanders seeking a better quality of life for their families were fleeing Seoul and moving into the new high-rise apartments in Seogwipo, on the south side of the island.

We viewed this rapid development with sadness. In reaction to the construction boom occurring everywhere, we decided to search for a doljip (stone house) in a coastal village. Not one within immediate view of the sea, but one within close walking distance. If we were to invest in property, it would have to be something that supported cultural preservation and allowed us to live in a historically embedded community. Having lived in big cities and California suburbs, we wanted to live more simply and in closer harmony with the natural environment and Jeju locals.

The first time I visited Jeju Island in the 1980s, I was immediately attracted to these iconic doljip with green, orange, or blue corrugated roofsits intersecting seams squeezed together like white cake frosting. From higher ground, the rooftops create a colorful patchwork. These days, the traditional dwellings have become more rare and expensive as mainlanders have purchased and converted them into rental units and cafs. So, I asked my friend Youngsook to scan the newspaper ads. In August 2015, she found one listing located in Aewol.

Although this area today is a tourist magnet, Aewol is located near significant historical grounds. Our village is not far from where Korean military units built a fortress to resist an invasion from Mongolia in the thirteenth century. I try to imagine that the roads I travel by car were once occupied by the Mongols for one hundred yearsled by Genghis Khans grandson, Yuan Kublai Khan, who brought with him 160 horses by ship.