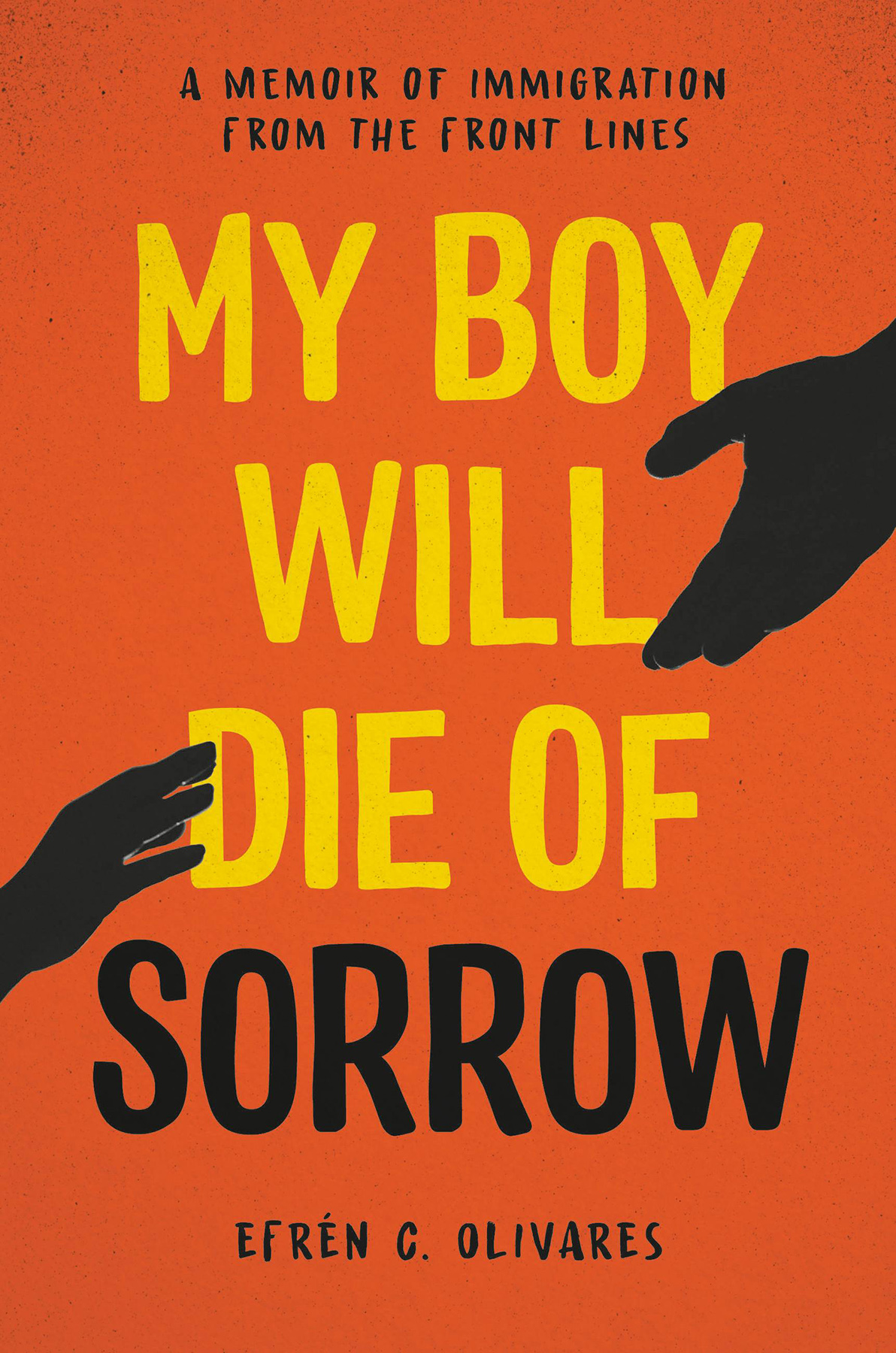

Efrén C. Olivares - My Boy Will Die of Sorrow

Here you can read online Efrén C. Olivares - My Boy Will Die of Sorrow full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Hachette, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:My Boy Will Die of Sorrow

- Author:

- Publisher:Hachette

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

My Boy Will Die of Sorrow: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "My Boy Will Die of Sorrow" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

My Boy Will Die of Sorrow — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "My Boy Will Die of Sorrow" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2022 by Efrn C. Olivares

Cover design by Terri Sirma

Cover photograph Fedortcov / Shutterstock

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

HachetteBooks.com

Twitter.com/HachetteBooks

Instagram.com/HachetteBooks

First Edition: July 2022

Published by Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Olivares, Efrn C., author.

Title: My boy will die of sorrow : a memoir of immigration from the front lines / Efrn C. Olivares.

Description: First edition. | New York, NY : Hachette Books, [2022] |

Identifiers: LCCN 2021059948 | ISBN 9780306847288 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780306847271 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: ImmigrantsFamily relationshipsUnited States.

Classification: LCC HQ536 .O38 2022 | DDC 305.9/06912073dc23/eng/20220217

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021059948

ISBNs: 978-0-306-84728-8 (hardcover), 978-0-306-84727-1 (ebook)

E3-20220517-JV-NF-ORI

To my family. And to the millions of families around the world who have dared to move across the earth in search of safety and opportunity.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

And the yelp

Of the coyote morphing

Into an infants cry, filled

With such longing, I wondered

What country Id stepped into.

From the poem Owl, by Jos Antonio Rodrguez

B orders separate. Borders divide and alienate. Borders make some feel secure, others trapped. Borders rise up and dissolve. Borders appear, disappear, reappear, and shift, sometimes slowly over decades and centuries, sometimes overnight. The Rio Grande River, which demarcates part of the boundary between the United States and Mexico, shifted its course time and againtaking the border with ituntil the 1970s, when the two countries agreed to fix the line for good with coordinates in a treaty. The river that served as a natural boundary turned out to be a poor marker to achieve the political purpose of a border: to separate. The U.S.-Mexico border, wrote Gloria Anzalda in the opening chapter of Borderlands/La Frontera, is an open wound, una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again.

This book explores this bleeding from a deeply personal perspective, a bleeding that sometimes gushes out violently, as it did in 2018, and other times slows down to a trickle. But it never stops.

In the summer of 2018, I found myself representing hundreds of immigrant families separated at the Texas-Mexico border under the Trump Administrations Zero Tolerance policy. That policy called for the mandatory prosecution of every person who crossed the border without authorization, charging them with the misdemeanor crime of illegal entry, or, if they had been deported before, the felony of illegal reentry. Zero Tolerance led to thousands of children being separated from their parents at the U.S. southern border, and I interviewed dozens of these parents and heard first-hand how Border Patrol agents took their children from them through deceit, subterfuge, and sometimes outright violence.

Twenty-five years earlier, I had been separated from my father when he migrated to the United States to look for work. He emigrated first, and the rest of us stayed behind, seeing him only when he was able to visit, but without him in the day-to-day of our lives in Mexico. For four years, we saw my father only occasionally, until we were finally able to join him. In 2018, it took me months to fully appreciate the extent to which the separation I lived when I was just a boy has informed the work I did, and continue to do, for immigrant families.

Although being without my father was not easy, my experience pales in comparison to those I have heard from my clients over the years. Like millions before us, we migrated out of economic necessity, in search of work and a better future. We were not fleeing violence, death threats, or persecution. To the extent migrating to the United States was a choice, it could be said that my family chose to be separated. The circumstances pushed us to migrate, and the law forced us to be separated, but if it was a choice at all, we had the privilege of choosing to be apart. By contrast, the hundreds of immigrant families I encountered in federal court in McAllen, Texas, had no say in the separation whatsoever: our government forced the separations upon them. What my family and I lived in four years of an episodic and voluntary separation, these families experienced in an intense, compelled, and violent rupture. And they were powerless to prevent it.

In the pages that follow, I strive to tell their stories as accurately as they shared them with me, and as faithfully as I lived through those weeks and months. In telling their stories, I also share part of my own, and reflect on what borders do to families. Whether over many years or in a flash, the effects borders have on those they separate are long-lasting. Sometimes it is the physical, geographical border, sometimes it is the legal and psychological, the indeterminable border between identities, cultures, and statuses that Anzalda so powerfully explored, at the edge where earth touches ocean / where the two overlap / a gentle coming together / at other times and places a violent clash.

This book is about the suffering and resilience of those who find themselves separated by a border. My hope is that it will stir us to question the foundation of our immigration laws, and push us to reimagine our understanding of political borders and those who cross them into one that is more humane for individuals, for families, and for communities on both sides.

(May 24, 2018)

G eorgina and I walked into the courtroom and found Azalea as she shuffled through the days docket looking for her handwritten notes, which she had made on the right margin in blue ink. Azalea was an assistant federal public defender in McAllen, Texas, and this morning she wore a spotless pastel suit that contrasted with the disarray happening in the courtroom. We only have five today, she said, referring to the separated parents of the day. A couple of moms, both from Guatemala, one of them with three children, ages seven, eight, and eleven. And three dads, each of them traveling with a son. This one is from El Salvador, and she continued flipping the pages hurriedly.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «My Boy Will Die of Sorrow»

Look at similar books to My Boy Will Die of Sorrow. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book My Boy Will Die of Sorrow and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.