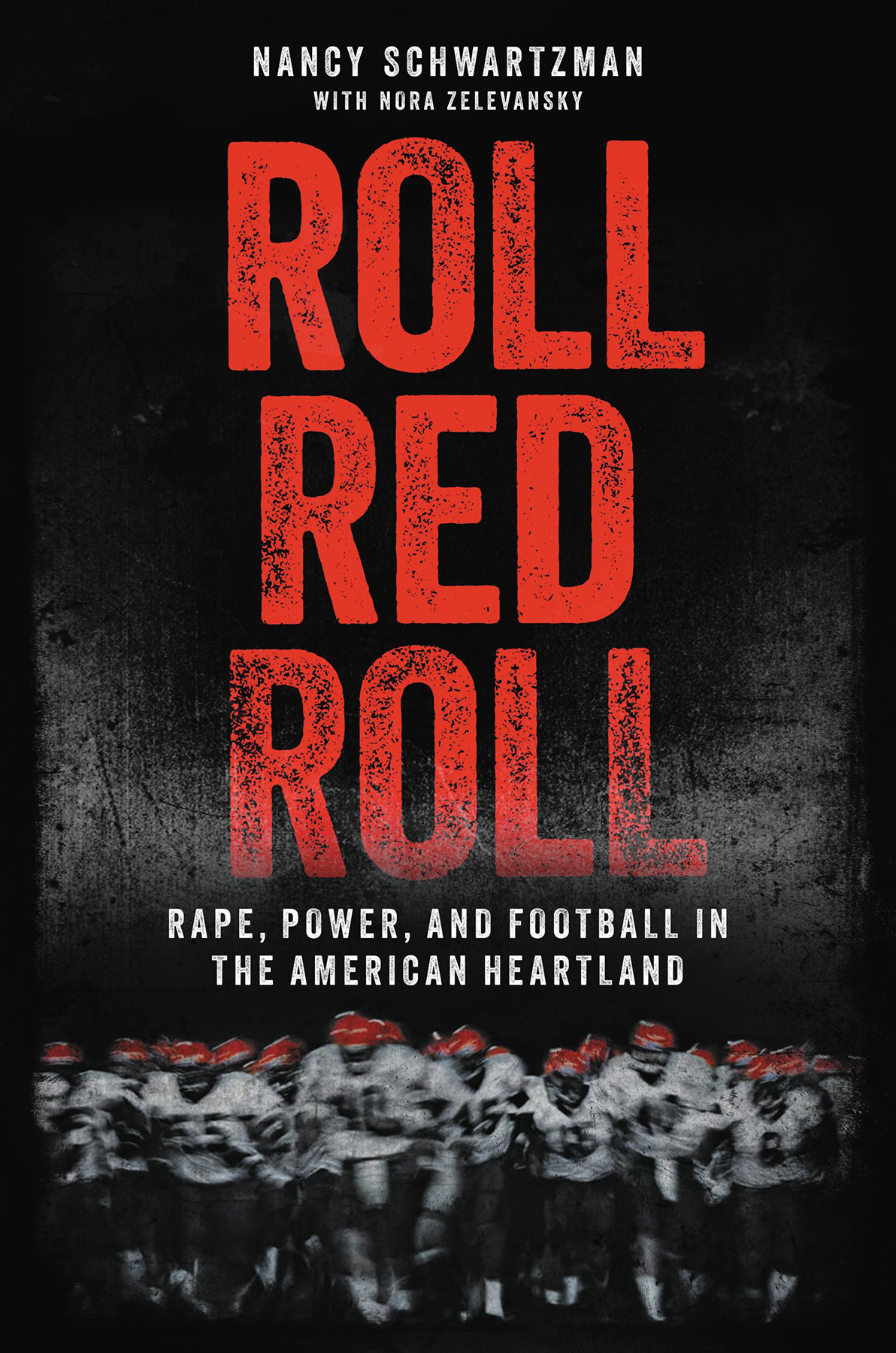

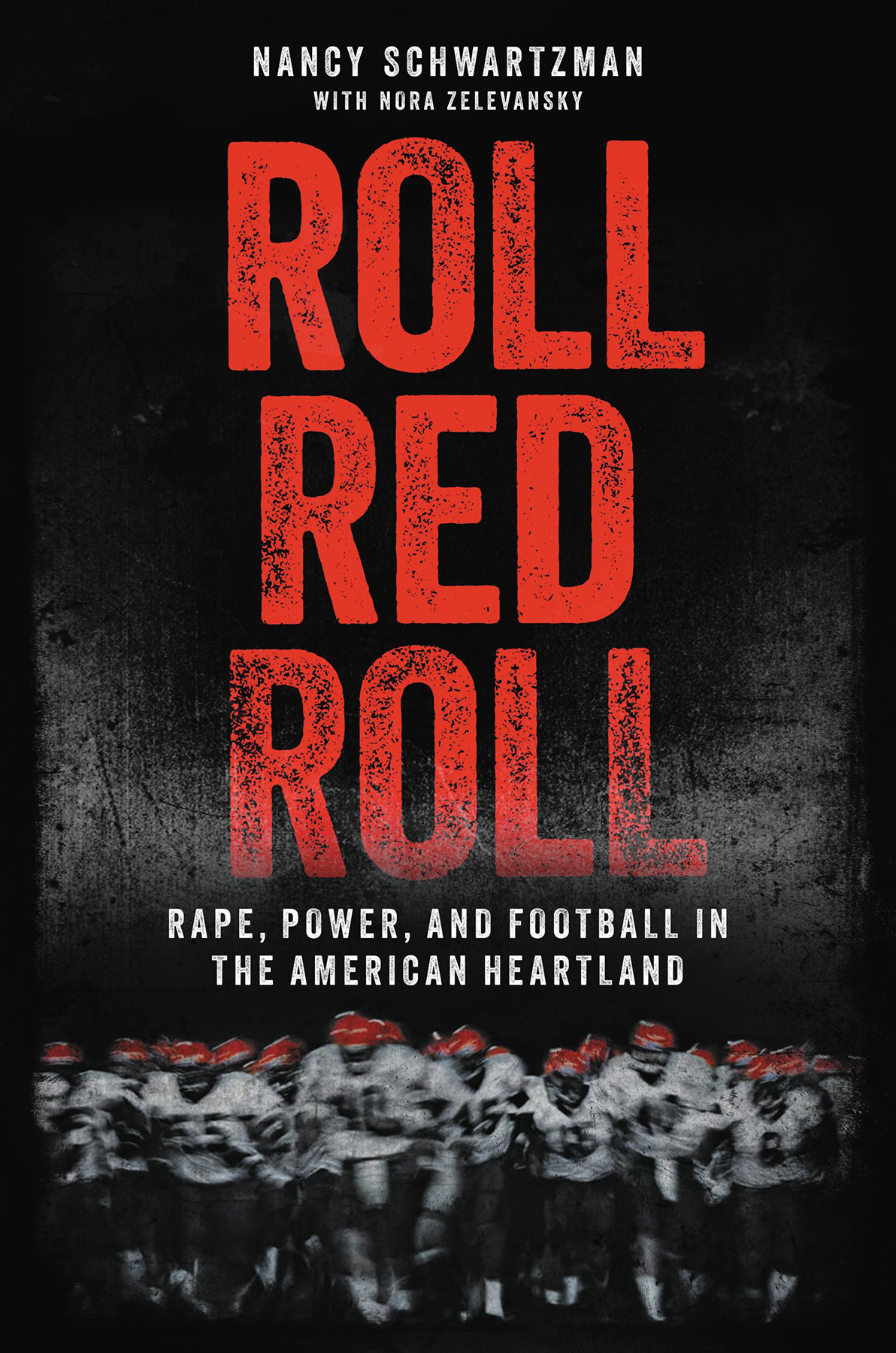

Copyright 2022 by Nancy Schwartzman

Cover design by Terri Sirma

Roll Red Roll documentary art: Image and title design by Rob Fuller, Composition by Briana Fahey; texture by Wilqkuku / Shutterstock

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

HachetteBooks.com

Twitter.com/HachetteBooks

Instagram.com/HachetteBooks

First Edition: July 2022

Published by Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events.

To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022936476

ISBNs: 978-0-306-92436-1 (hardcover), 978-0-306-92438-5 (ebook)

E3-20220513-JV-NF-ORI

For my beloved father, Dr. Robert J. Schwartzman,

a die-hard football fan, who held this story

with me, every step of the way.

19392021

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

I N DECEMBER 2012, when I first learned of the Big Red football case in Steubenville, Ohio, I almost wrote it off as just another awful story. As a human rights activist and documentarian focused on gender-based violence, Id seen countless rape cases played out in the press, the focus primarily on the victims role and complicity, rarely on the perpetratorstheir behavior, the need for consequences. The Steubenville story seemed like all the others. After all, the Department of Justice estimates that one in six women are the victims of attempted or completed rape annually, and we know that those numbers are higher in actuality, as rape is a vastly underreported crime. The risk for young women ages eighteen to twenty-four is three times higher than the average population. In reality, the average rapist has to commit twelve assaults before going to prison. Steubenvilles story is practically the norm in the United States.

But as I learned more about what happened, adrenaline began to rise in my chest: this case, which involved the sexual assault of a teenage girl by high school football players in a downtrodden former steel town, offered a window into rape culture unlike anything Id seen before. The rape was live-tweeted by the local teenage boys, who anticipated, observed, and recounted it without concern for privacy, accountability, or the girls well-being. As a result of their tweets and texts, in the aftermath they couldnt deny what theyd done. This was a glimpse at the perpetrators mindset, illuminating the different roles people play in an assault like this oneand why. It demonstrated how easily a seemingly average set of circumstances can spiral into something horrific when theres a culture of enablement, entitlement, and denial.

I set out to make a documentary film about the crime and ensuing case. I would ultimately arrive on the ground in Steubenville a year to the day after Jane Does assault, prepared to discover for myself what kind of environment birthed the incident. I spent the next three years filming, traveling in and out of the town, learning its rhythms, talking to locals, and recording their often-divided perspectives. Over that time, I learned that a powerful economic force of boosters funneled big money into Steubenville High Schools Big Red football program. I learned that the depressed communitys sense of self, fragile after years of economic instability, hinged on the success of that team. And I learned about a legacy of systemic sexual abuse that had hung over Steubenville for generations. Thats one of the reasons why Jane Doe herself does not feature prominently in the work Ive done around this case. What needs investigating and interrogation isnt about the victim. Its about the perpetrators, the bystanders, the culture that created them and then, inadvertently or not, allowed them to thrive. For a long time, nothing had changed. And I came to realize that the culture of this place didnt just reflect the residents of this Ohio town; it was the legacy of our shared history. This was a microcosm. This was our heartland. This was our America.

This is our future if we dont make a change.

I went to a high school with alcohol-fueled weekend parties not unlike those of Steubenville High School. A varsity tennis player, I came from a sports-loving family and understood intense relationships with coaches, what it meant to your family for you to succeed on the field or court. When the entire town of Steubenville, or any community, comes together to celebrate in the stands on Friday nights, it can be a beautiful thing, but not when celebrating the boys takes precedence over protecting the girls.

When digging into the trove of social media and text messages traded between those involved, I felt like I knew these teens, especially the ringleaders. They reflected some of the same attitudes of my peers growing up, and even some of my own. If I had stayed in my hometown, a tight-knit and somewhat conservative community outside of Philadelphia, my worldview might not have shifted. I took a different pathleft home, moved to New York City, and traveled the world. Motivated by my own experiences and those of friends and even strangers, I chose activism, using storytelling and technology to create safer communities for women and girls. Before shooting my film, I created Circle of 6, an award-winning mobile app designed to reduce sexual violence among Americas youth. Recognized by organizations from the Obama White House to the United Nations, its been used by more than 350,000 people in thirty-six countries. The Steubenville story, at the intersection of rape culture, technology, and athletics, is an amalgamation of everything that makes me who I am.

Understandably, I was fascinated by the undercurrents of this disturbing situation. Rape culture wasnt unfamiliar to meI could recognize that I was born and bred inside of it like everyone elsebut the social media platforms were new. I wanted to understand what empowered boys to talk about rape so casually and broadcast it so publicly. What was specific to this place, and many others today, that enabled unabashed rape culture like this to fester? It was all out there. Prosecutors sifted through more than 360,000 text messages and hundreds of tweets to uncover the truth. And, as I read the texts and social media posts myself, the lack of empathy and remorse chilled me, as it did many others across the country who followed this story.

While technology is mainly neutral, the way we use it is variable. Seeing it overlap in the gender space, I was amazed at the power of social media: to incriminate, to empower, and to shine a light in the darkness.