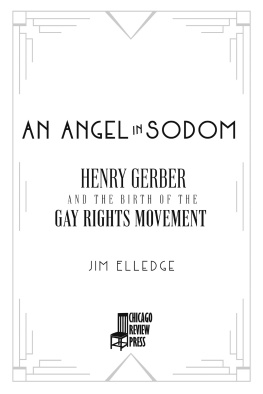

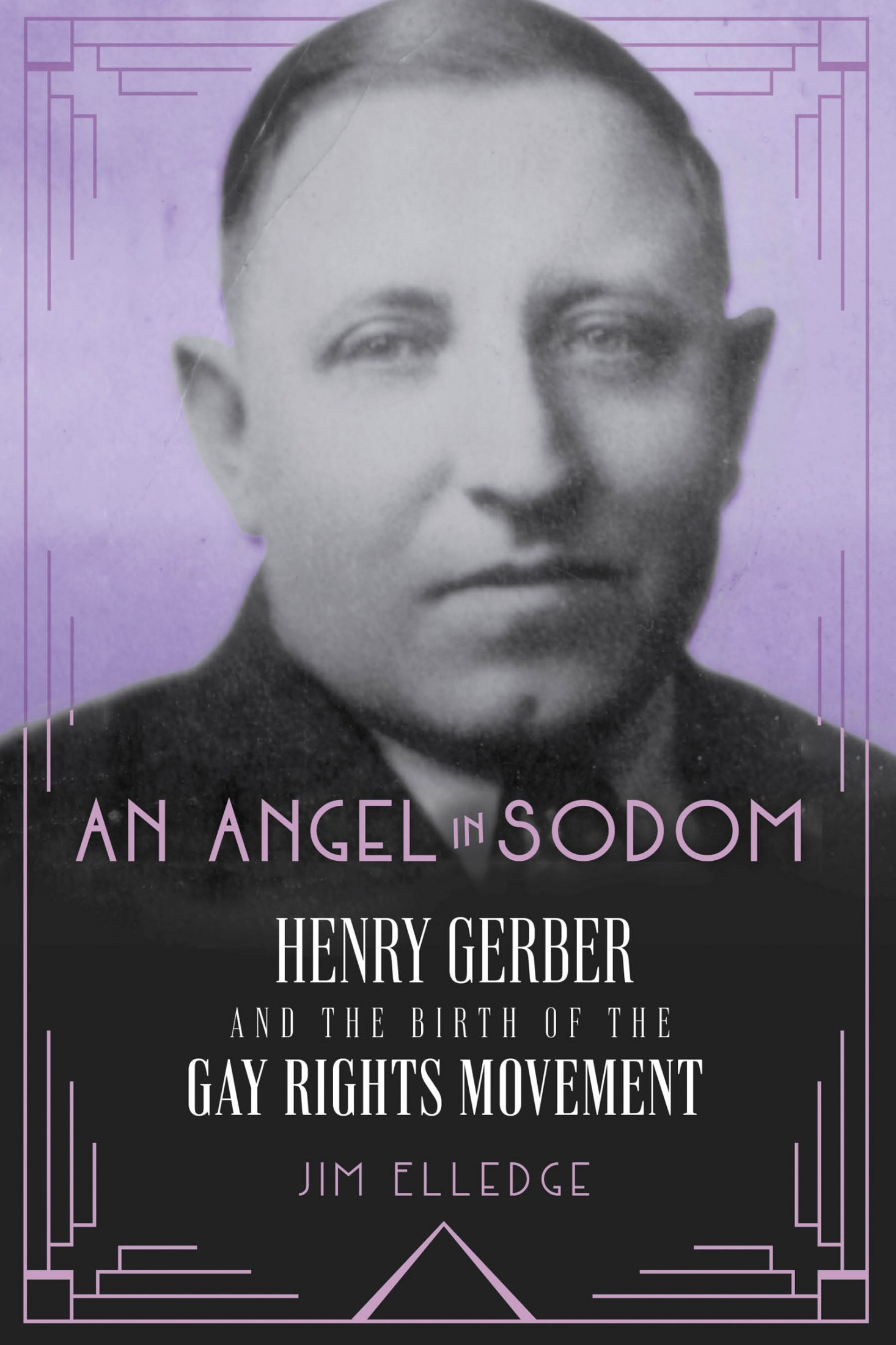

Copyright 2023 by Jim Elledge

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-64160-568-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022941128

Typesetting: Nord Compo

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

This digital document has been produced by Nord Compo.

For David

To hell with the do-gooders and filthy hypocrites

trying to tell us how to fuck.

Fuck em!

Henry Gerber

Contents

Acknowledgments

NO BIOGRAPHER, OR SCHOLAR of any discipline, can conduct research without the support of librarians and archivists. For me, those include the staff of the Chicago History Museum, Chicago; the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Historical Society, San Francisco; the Homosexual Information Center, California State University, Northridge; the Illinois State Archives, Springfield; the J. D. Doyle Archives at http://www.jddoylearchives.org; the Kinsey Institute, Indiana University, Bloomington; Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, New York; and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, University of Southern California Libraries, Los Angeles. I thank them sincerely for all the work they have done to provide me with information I needed for this book.

But there are more personal acts of support that friends and loved ones perform that also need acknowledgment. To Damon Dorsey, Romayne Rubinas Dorsey, Maggie Mattison, Mike Mattison, and Alison Ummingerwho all added to this volume in ways beyond my powers of descriptionI tip my hat and send my love.

My editors at Chicago Review Press, Jerome Pohlen and Devon Freeny, and copyeditor Alexander Caputo went beyond the call of duty and deserve accolades beyond measure.

Finally, my husband, Aelred B. Dean, can never be repaid for the patience and love he showed me during the process of writing this and previous books. Neither thanks nor expressions of love quite offer what he deserves, but regardless, I send them his way, hoping that they might repay him, at least in a small amount.

An Introductory Note

Henrys Epistles to the Perverts

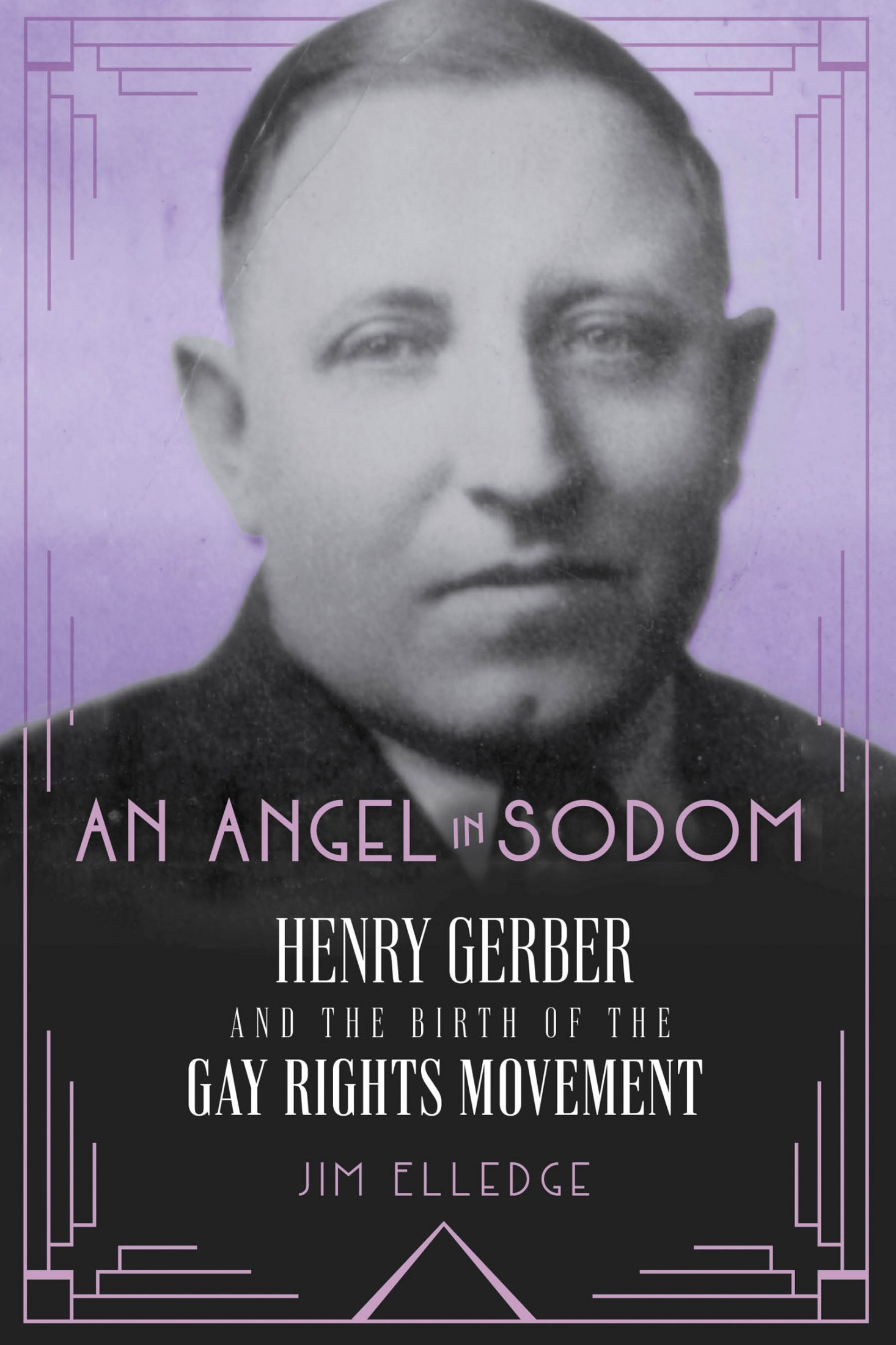

I FIRST LEARNED ABOUT HENRY GERBER when, in 1976, I bought and devoured Jonathan Ned Katzs Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. This seminal volume in queer studies became a classic the moment copies arrived in bookstores across the nation. A documentary, it provided thousands of letters, photographs, and a variety of historical records to anyone wanting to know about the queer past. Among them, Katz included several pages about Henry Gerber and his Society for Human Rights, which Gerber founded while living in Chicago in 1924. It was the first organization formed in the United States to attempt to work toward reforming the plight of gay men, to publish a journal focused on them, and to be legally incorporated as an organization.

As time passed, I used Katzs volume off and on for many of the projects I eventually undertook. It pointed me to sources for several of my own books, including Henry Darger, Throwaway Boy (2013), Masquerade: Queer Poetry in America to the End of World War II (2004), and Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Myths from the Arapaho to the Zui (2002).

Over the years, scattered mentions of Gerber and his activities popped up here and there during my research in footnotes and paragraphs in articles, but I never came across an actual biography. I assumed that the documents needed to write the story of his life didnt exist. All that changed when, several years ago, I visited ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives in L.A. to work on a project. The archive, I discovered, holds a treasure trove of Gerber and Gerber-related materials, specifically his, Frank McCourts, and Manuel boyFranks exchange of letters, what boyFrank dubbed Henrys epistles to the perverts.

The dynamics of the three-way correspondence is fascinating. boyFrank and McCourt were members of Contacts, a correspondence (or pen pal) club that Gerber headed in the 1930s. He had moved to New York by then. Correspondence clubs were important to many gay mens lives in the first half of the twentieth century. Through them, men passed information back and forth about all sorts of topics, including hot spots for cruising in specific cities, formed friendships and romantic relationships, and discussed societys various crusades against them. boyFrank instigated the trios correspondence when, on September 22, 1935, he wrote to Gerber, thanking him for sending him a notice that reminded him his membership in Contacts was about to lapse and to let Gerber know that he had recently begun exchanging letters with three male members of the club. Gerber, an atheist, had made his stand against organized religion known in several of the articles he wrote for a magazine he had published a few years earlier, Chanticleer, and boyFrank told him that he was also an atheist and gave his reason: Christianitys teachings against sexual expression. In the process, he also hinted he was gay. At the time, they were subject to extremely punitive laws, and they had to be circumspect in their dealings with other people, especially in their correspondence with strangers, which could be opened legally by postal authorities. He concluded the letter two pages later, one of the shortest letters he would ever write Gerber, with his thanks to Gerber for hearing him out. Their correspondence was sporadic during the rest of the 1930s but picked up in February 1940 and continued, off and on, for approximately twenty years.

McCourt joined in the letter writing on January 30, 1940. Gerber had disbanded Contacts by then, and boyFrank wanted someone to revive it. He even badgered Gerber to resurrect it. boyFrank learned through Contacts about McCourt and his hobbycollecting and taking physique photographs, a euphemism for black-and-whites of naked or near-naked men, usually bodybuilders but also any physically fit maleand sent him a letter. That letter has been lost, but he must have asked about McCourts collection, if he were willing to take the helm of Contacts, or if not, if he knew someone who might. McCourt wasnt at all interested in stepping into Gerbers shoes, didnt know anyone who would, but supported boyFrank in his quest, especially hoping for a men-only club. He concluded the letter by inviting boyFrank, who lived on Staten Island, to his brownstone on West 140th Street in Manhattan, which he shared with his partner Charles Chuck Ufford, for cocktails and to check out his photograph collection. boyFrank and McCourts letters often focused on physique photographs, including information on the amateur and professional photographers who sold them. McCourt sent many he had taken to boyFrank, and his last letter to boyFrank, which was barely a note, included several of his recent ones.

McCourt and Gerber didnt correspond with one another nearly as often nor as long as boyFrank and Gerber did. Their friendship was strained by religion. Because Gerber, the atheist, realized that Christianitys regulations against homosexuality and its partnership with city, state, and federal legislators created the struggles facing queer people, he didnt completely trust McCourt, the devout Roman Catholic. Gerber believed sex was a natural expression and couldnt understand how any gay man could align himself with those who wanted to punish them for following their natural inclinations.