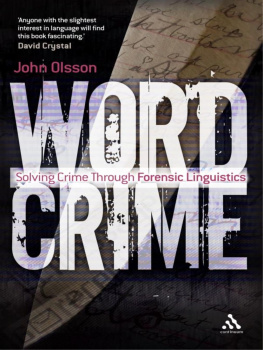

Wordcrime

Also Available from Continuum:

Forensic Linguistics: Second Edition

John Olsson

Where Words Come From

Fred Sedgwick

Language: The Big Picture

Peter Sharpe

Understanding Language: Second Edition

Elizabeth Grace Winkler

Language and The Law

Sanford Schane

The Language Instinct Debate

Geoffrey Sampson

The Grammar Detective

Gillian Hanson

The Language of The Third Reich

Victor Klemperer

WORDCRIME

SOLVING CRIME THROUGH

FORENSIC LINGUISTICS

John Olsson

Continuum International Publishing Group

The Tower Building 11 York Road, London SE1 7NX

80 Maiden Lane, Suite 704, New York, NY 10038

www.continuumbooks.com

John Olsson 2009

First published in 2009

This paperback edition published 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978-1-4411-9352-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Publisher has applied for CIP data.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

What is forensic linguistics? If you have gotten this far, it is a question that you may have some answers to already. On the other hand, forensic linguistics might be a subject that you have heard nothing on, but want to know more about.

My name is John Olsson, and for the past 15 years I have been (and still am) the worlds only full-time forensic linguist. This book concerns my work, and is designed in part to illustrate how forensic linguistics can help solve crime. Before I move onto this though, I would like to go over some background information. Let me detail in brief how the science of forensic linguistics came into being.

In 1968 a Swedish linguist working at the University of London heard about a case which had occurred a number of years previously. It concerned the murder of several women and a baby at an infamous London address, 10 Rillington Place, Kensington. Rillington Place became so notorious that the authorities were eventually forced to change its name to Ruston Close at the request of the people who lived there. However, the bad associations remained and eventually the local council demolished the entire street and a new development of houses was constructed there in the 1970s.

The ground-floor tenant of 10 Rillington Place was one John Christie, a quiet perhaps even shy man, apparently contentedly married. Above him lived Timothy Evans and his wife Beryl and their baby daughter. Evans disappeared from Rillington Place in 1949 and questions began to be asked about the whereabouts of his wife and baby. In November of that year, Evans handed himself into police in South Wales where he had been living with his uncle at Merthyr Tydfil. Forensic linguistics comes into the story at this point because Evans was supposed to have given several statements to the police confessing to the crime. Evans was found guilty partly on the basis of the statements and partly on the basis of evidence given by John Christie. Evans was hanged in 1950. Later Christies wife disappeared and neighbours began asking questions about his odd behaviour. After Christie moved out another tenant occupied his flat and, while attempting to put up a shelf made a gruesome discovery: a partly clothed womans body. When police arrived at the house they found evidence of several other murders. Christie was eventually tracked down, charged, found guilty and later hanged. Not long before he died he confessed to the murder of Evans wife and probably of their baby. Despite urgent requests to investigate these claims before Christies execution date the Home Secretary refused to halt the hanging and Christie was put to death in July 1953. The crimes he had confessed to for which Evans had been hanged continued to be attributed to Evans for over a decade until journalist Ludovic Kennedy became interested in the case in the 1960s and the statements also drew the attention of a Swedish professor working at the University of London. Jan Svartvik examined the statements and concluded that they contained not one but several styles of language, most of which were written in what is known as policemans register. Svartviks analysis and the unwavering campaign by Kennedy caused the Home Secretary to reverse the conviction and Evans was posthumously pardoned. This was probably the first murder appeal in the world in which linguistics played a prominent part. Because Svartvik used the term forensic linguistics in his report on the statements he is credited with being the father of the discipline.

In the 1990s the case of Derek Bentley drew the attention of linguists at Birmingham University where I was doing postgraduate research in linguistics. Several anomalies appeared in the statement Bentley is supposed to have dictated to police officers after the shooting of Police Constable Sidney Miles at a burglary in South London by Bentleys co-burglar, Chris Craig. A number of other previously accepted confessions now fell under suspicion and one after another several convictions were quashed, largely on the basis of evidence provided by ESDA trace, an electrostatic procedure which has certain elements in common with photo copying and reveals indentations from other sheets if several sheets were placed on top of each other in the course of writing.

In 1994 I founded the Forensic Linguistics Institute in the United Kingdom which has since become one of the leading linguistics laboratories in the world. Along with my colleagues I examine texts of all types for authorship, authenticity, interpretation of meaning, disputed language and other forensic processes. An early case involved the analysis of an alleged terrorists statement to police at Paddington Green Police Station in the mid-1980s. Since that time I have handled nearly 300 forensic linguistics investigations. These have ranged from examining the language of suicide letters for genuineness, assessing threat in extortion demands, evaluating police interview tapes for alleged oppressive interviewing (a rare occurrence these days), and the authorship identification of many hundreds of letters, emails and mobile phone texts in a range of inquiries from murder to extortion to witness intimidation, sexual assault and internet child pornography. I get commissioned by police forces, solicitors, international companies and organizations, and even private clients who have received hate mail from someone who might live just down the road or even next door.

In an early case I was asked by the president of a dog club in the midwest of the United States to see whether a spate of hate mail letters the club had received came from one of their own members. The most likely author turned out to be an elderly mild-mannered lady who had devotedly carried out the clubs administrative affairs for many years, but who had been disappointed by the failure of one of her pets to win a prize at the clubs annual dog show. It may come as something of a surprise, but hate mail also occurs within families: in one case a disgruntled woman had become infuriated at the success of her younger brother in his hotel business and wrote a spate of poison letters to the local chamber of commerce not only denigrating his efforts but insulting his wife, accusing him of nazism and claiming that the hotel often hosted white supremacist weekends. In another case a teenage girl grew jealous of her sisters impending marriage and tried to poison her against the bridegroom. On the other hand, not all hate mail is from family members: I recently had to attempt an identification in which a middle-aged male, having been sexually rebuffed by a teenage boy, then wrote to the boys parents accusing their son of being a child molester. The boys father perhaps as a result of this accusation against what he perceived to be his familys honour then committed suicide.

Next page