Derek Jarman

PHARMACOPOEIA

A Dungeness Notebook

Contents

About the Author

Derek Jarman was born in London in 1942. His career spanned decades and genres, from painter, theatre designer, director, film maker, to poet, writer, campaigner and gardener. His features include Sebastiane (1976), Jubilee (1978), Caravaggio (1986), The Last of England (1987), Edward II (1991) and Blue (1993). His paintings for which he was a Turner Prize nominee in 1986 continue to be exhibited worldwide, and his garden in Dungeness remains a site of pilgrimage to fans and newcomers alike.

ALSO BY DEREK JARMAN

Dancing Ledge

Derek Jarmans Garden

Modern Nature

Chroma

Smiling in Slow Motion

At Your Own Risk

Kicking the Pricks

Editors Note

This book is composed of extracts from across Derek Jarmans published works. In particular, it draws upon his journals, Modern Nature and Smiling in Slow Motion, his ode to colour, Chroma, and the posthumously published, Derek Jarmans Garden. Pharmacopoeia was conceived as a celebration of Derek Jarmans nature writing and was begun with the approval of Keith Collins and the Keith Collins Will Trust.

Foreword

Artists live in houses and make work in them; they make work in other peoples houses, too. There are countless plaques on countless walls across the globe running to catch up with the trail of inspired moments down the ages: here he wrote such and such, between the years blank and blank, she completed so and so, he lived here, she boarded here, even for a week/a night, they slept here. Artists also work on the bus, in trains, in cafes and on the sides of roads, under trees and canvas and bedclothes by torchlight. Lets maybe conclude that art is generated everywhere.

This idea flicks a beautiful switch, in my view. It de-exoticises and brings closer the idea of an artists work, rubs it into the landscape of regular lived human life. This is closer to an accurate picture, as I know it to be. Artists writers, painters, sculptors, film-makers, performers, musicians, philosophers make work within our lived days and in between the doorways of a social mortal span It would be impossible to catch, therefore, like a butterfly in a net, every site of every artists creative inspiration. Lets just say that might be The World Itself, after all.

But there are some places that represent something worth preserving not, in fact, simply because they represent a past point in history and a footnote regarding a single life once lived, but because of the influence they had on that life, the working practice they made possible, the liminal energy they afforded and might still afford open souls seeking their nourishment.

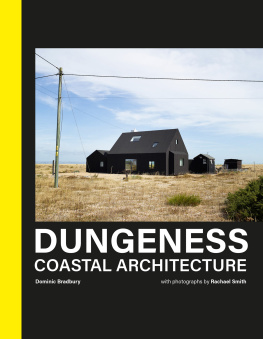

I first saw Prospect Cottage the day that Derek did. We had driven down to find a bluebell wood to shoot in: I had remembered a wide bluebell expanse in Kent from my schooldays there. We pottered down in my ramshackle little car and found the idyll now covered in concrete. A little disheartened, we headed for the coast, abandoning bluebells in search of fresh air. Dereks father had recently died and left him a small inheritance. Life on Charing Cross Road had become somewhat overstimulating, and Derek was looking for a place to be quieter. He had a friend who lived on the shingle at Dungeness, that pocket of southern England which sounded to me so tantalisingly Scottish, the dangerous nose, the Fifth Quarter of the globe

We drove along the shore road and stopped to skim flat stones like flints into the waves, pocket a few pebbles that we found with perfect holes in them, little knowing that this would be the first of a thousand afternoons for us spent in much the same way. As we were turning to drive back to London, we saw, at the same moment, a small black-painted wooden house with yolk-yellow window frames on the left-hand side of the road facing the sea. It had a For Sale sign stuck in the stones at its feet. I remember distinctly turning in without a word and stopping the car.

We knocked on the door, were let in by the charming lady who lived there and, after a tour that cannot have lasted longer than fifteen minutes, were back on the road heading north. Derek decided before we reached Lydd that he would buy it. And within a couple of months, we were taking down chintz curtains and prising open the lid of the first of gazillion gallons of pitch-black paint with which to anoint his new kingdom.

The pleasure he took in transforming this modest bungalow into the Tardis he created the setting for his films, his books, his garden, the solace of the sea and the peculiar glamour of the nuclear power station (!) especially at the moment at which he discovered himself ill is incalculable. He made of this wee house, his wooden tent pitched in the wilderness, an artwork and out of its shingle skirts, an ingenious garden now internationally recognised. But, first and foremost, the cottage was always a living thing, a practical toolbox for his work.

Our initiative to preserve this treasure that might otherwise be lost to our cultural landscape is not that we are seeking to set in a time warp a precious object of historical significance for posterity only; but, crucially, to resuscitate and ensure the continued vibrational existence of a living battery: to clear space around it and feed the energy of a resource that was only ever intended to be that. This is a vision not of taking but of giving.

Just as Derek was self-determinedly dedicated to process above product, to collective work, to empowering voices that might feel alienated, my excitement about this vision for Prospect Cottage lives in its projected future as an open, inclusive and encouraging machine for the inspiration and functional working lives of those who might come and share in its special qualities, qualities that, as a young artist, I was lucky enough to benefit from alongside Derek and so many of our friends and fellow travellers.

Beyond the plaques, there are some places that offer the vision of a continued evolution as a point of encouragement and metaphysical enlightenment. I suggest that Prospect Cottage is such a place.

Derek memorably said that he would prefer his works after his death to evaporate and disappear. For what its worth, and in honour of the supremely contrary nature of my friend, I feel fully confident that he would be extremely enthusiastic about the generosity of this vision for the continuance of the life of his beloved Prospect Cottage as a possibility for future artists, thinkers, activists, gardeners to gain from it the practical and spiritual nourishment it lent him and for which he was and is eternally grateful

Tilda Swinton

2020

to whom it may concern

in the dead stones of a planet

no longer remembered as earth

may he decipher this opaque hieroglyph

perform an archaeology of soul

on these precious fragments

all that remains of our vanished days

here at the seas edge

I have planted a stony garden

dragon tooth dolmen spring up

to defend the porch

Next page