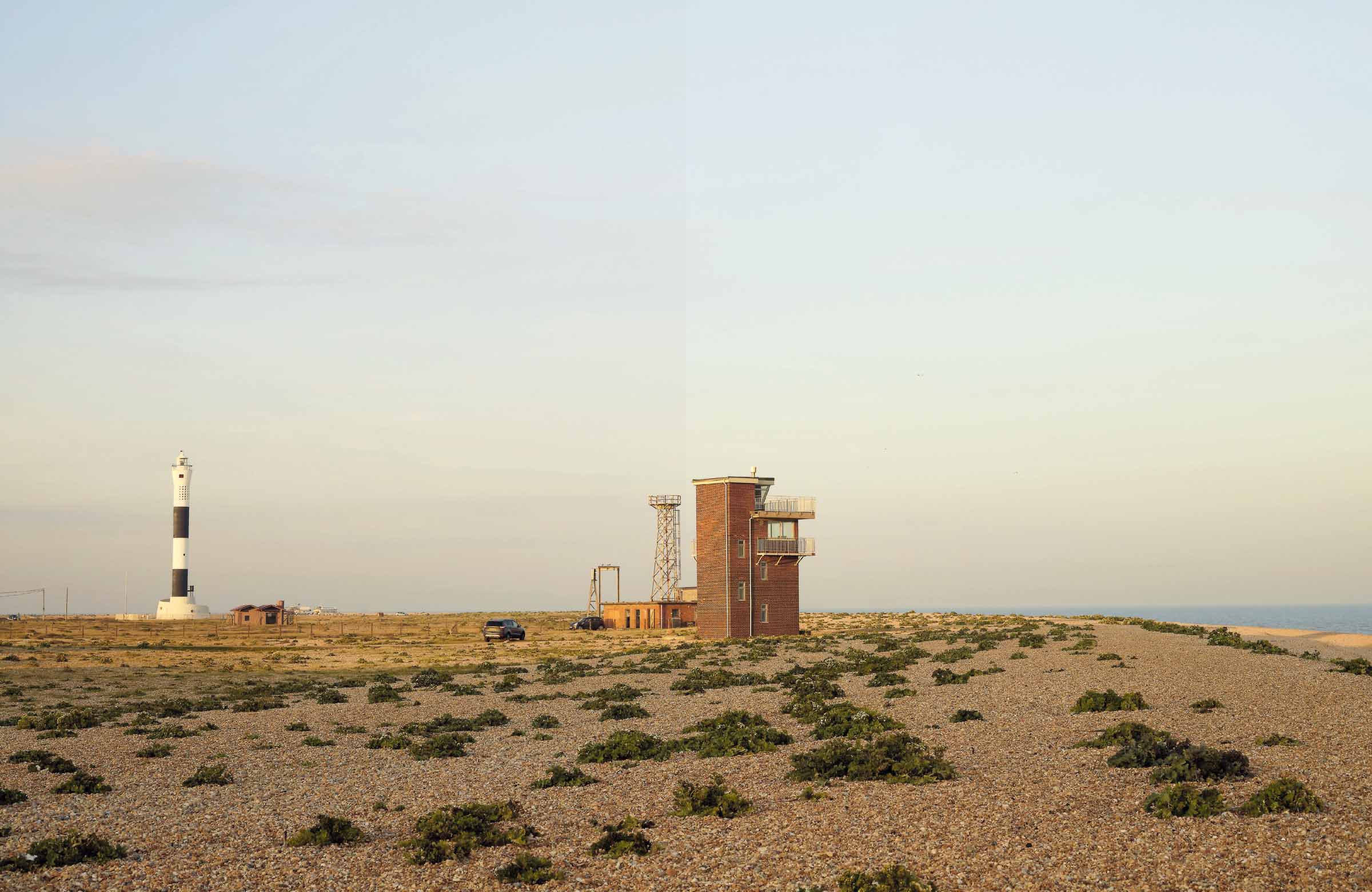

Stray buildings and structures of all kinds inhabit the headland, including the rectangular wooden bird hide up on the shingle overlooking an area of the sea known as The Patch.

Old fishermens floats and metal carry crates are among the many found objects that add to the character of the garden at Derek Jarmans .

Pavilion

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Pavilion

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2022

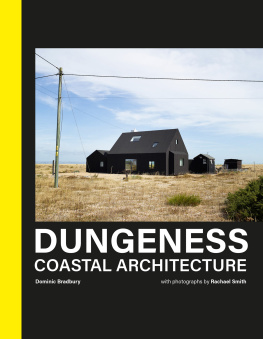

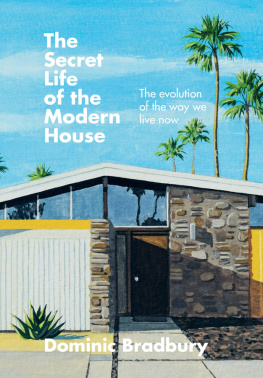

Text copyright Dominic Bradbury 2022

Photography copyright Rachael Smith 2022

Dominic Bradbury asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 9781911663737

eBook ISBN: 9780008601669

Version date: 2022-08-30

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

- Change of font size and line height

- Change of background and font colours

- Change of font

- Change justification

- Text to speech

- Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9781911663737

Contents

A view of the building just behind it.

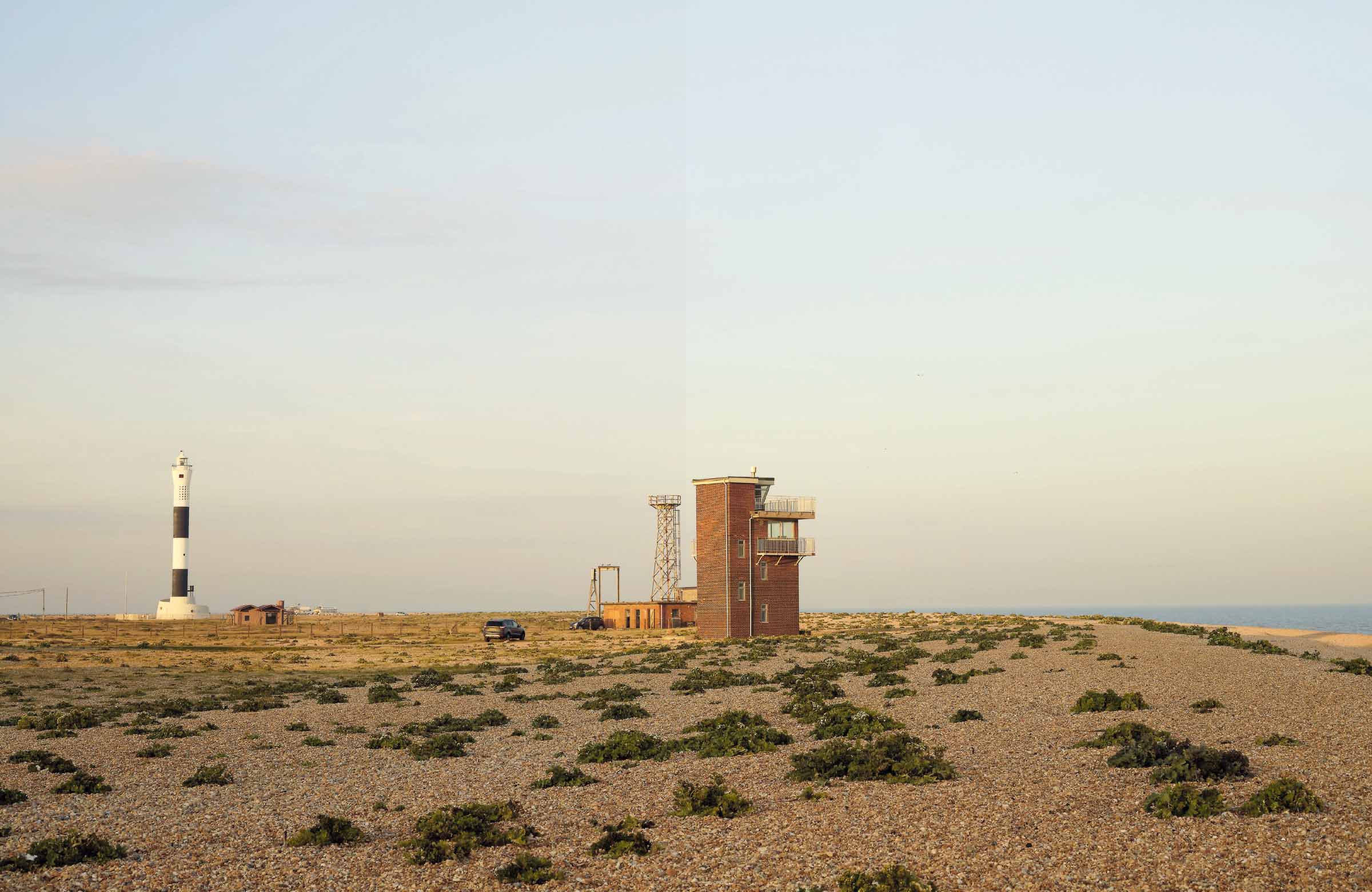

The headland and hamlet of Dungeness has a unique character all of its own. This is a place of poetic extremes and eclectic charms, which makes it such a special place to live in or to visit. The way that the shingle beach pushes out into the English Channel makes it a key marker for shipping and for geographers, but also helps to set the place apart both physically and emotionally. The landscape is so open and exposed that people here often talk about feeling as though they are part of the Ness itself. Its a feeling enhanced by a healthy tradition of making do without borders, barriers and fences, even around private cabins and cottages, which is another important trait in the personality of the place.

Dungeness is one of those escape points where the rhythms of nature can be keenly felt but here they are accompanied by man-made movements, adding to the balletic quality of everyday life on the headland. There are the natural motions of the tides, the dawn and sunset, all of which become explicit in Dungeness, along with shifts in the open skies, with any changes in the weather visible many miles away. Add to this the patterns of the changing seasons, particularly the gradual adjustment from the challenges of the winter to the awakenings of spring, which are dramatic even in this shingle hinterland between land and sea, along with the migration patterns of the incoming and outgoing birds.

There are also the rhythms created by the continual maritime traffic out in the Channel and the daily rituals followed by the fishing boats. On a clear night, not only are the running beacons of the ships visible but also the blinking shore lights over on the French coast, while at any time of year Dungeness lighthouse casts its own constant spell across the beach and the water. Then there is the rhythmic hum coming from the extraordinary elephant in the room, the power station. Yet, after a time, the power station somehow seems to fade into the background, partly because your gaze is constantly being drawn elsewhere and particularly across the shingle to the sea.

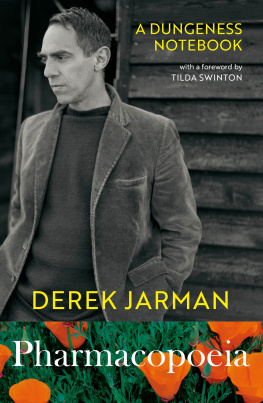

One of the headlands most revered residents, Derek Jarman, described the Ness as a desolate landscape where the silence is broken by the wind, and the gulls squibbling round the fishermen bringing in the afternoon catch. But as Jarman himself testifies in his book Modern Nature, Dungeness is not all desolation: there is a rich ecosystem here, so much so that the headland is part of a nature reserve that is home to many rare species of plants and other kinds of wildlife, while the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) also has a dedicated reserve alongside the Dungeness Estate. Jarman famously delighted in creating his own garden at ).

Remnants of one of the skipway tracks, once used for carting fish across the shingle; they are among the many historic markers that can be seen on the headland.

A view from the living-room window of the building and the sea beyond.

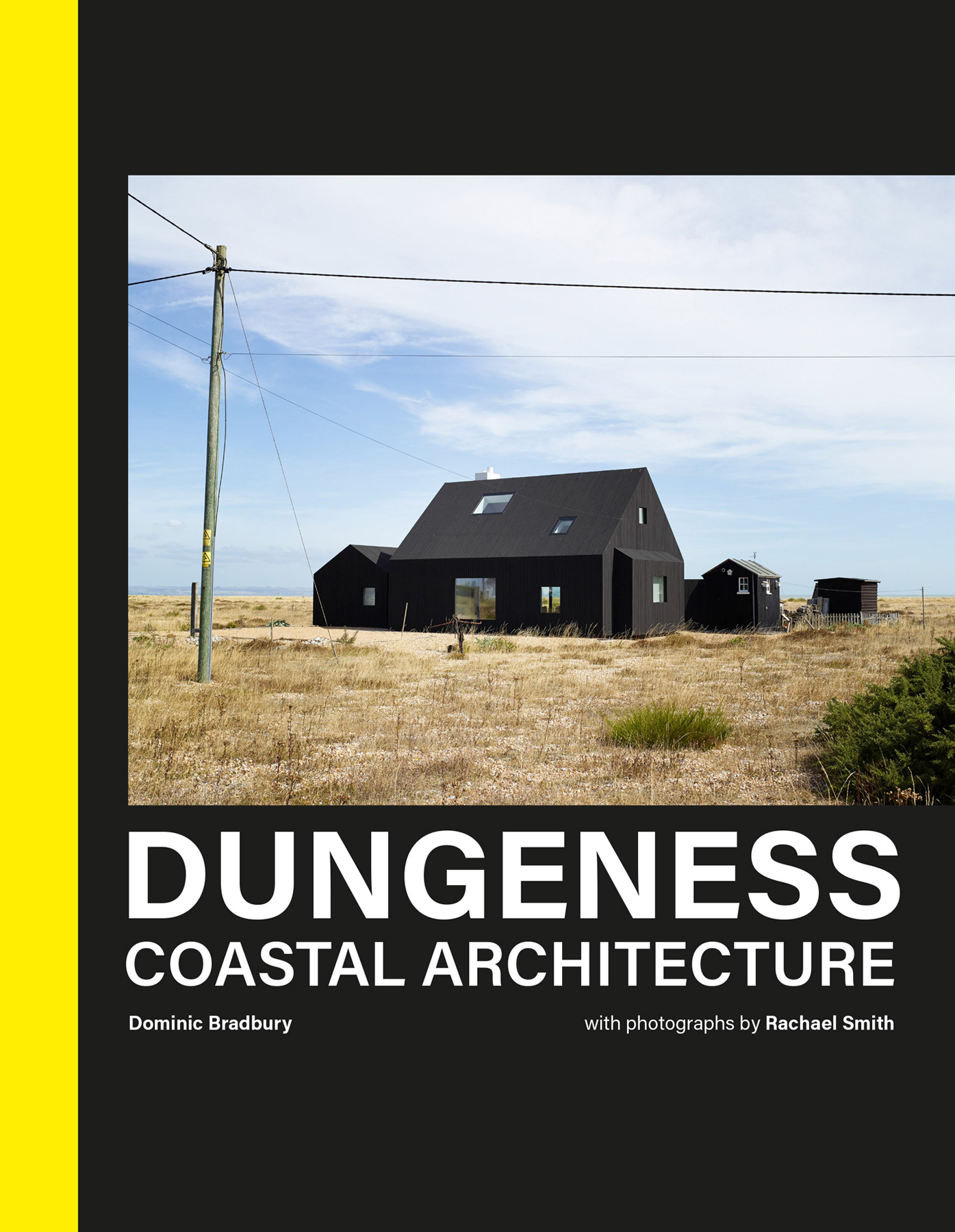

All of these things help to make Dungeness a place apart, but its unique collection of houses and cabins are unique in themselves and provide the focus for much of this book. Dungeness is little more than a hamlet with barely a hundred homes, yet within it stand buildings and structures full of history, character, originality and invention. Some are fishing-family cottages that have grown and evolved over many years, while others date back to the 1920s, when the staff of the South Eastern Railway were offered redundant rail carriages at knockdown prices, along with a small parcel of shingle on which to put them. These beachside carriage houses, which were also extended over time, marked the start of Dungeness transition into a micro resort, enlarging the community and its modest stock of homes. Together, the fishing cabins and the carriage houses created a characterful Dungeness vernacular.

Over recent years a number of these existing buildings have been sensitively updated and upgraded to create houses better able to withstand the extremes of the winter, harsh weather and salt-water spray. But there have also been imaginative conversions and adaptations of other non-residential buildings here that have added to an already eclectic mix. These include wartime buildings, structures used by Trinity House to test out navigation systems and new technology during the 1950s and 60s, and other redundant structures such as the . All have been restored and revived.