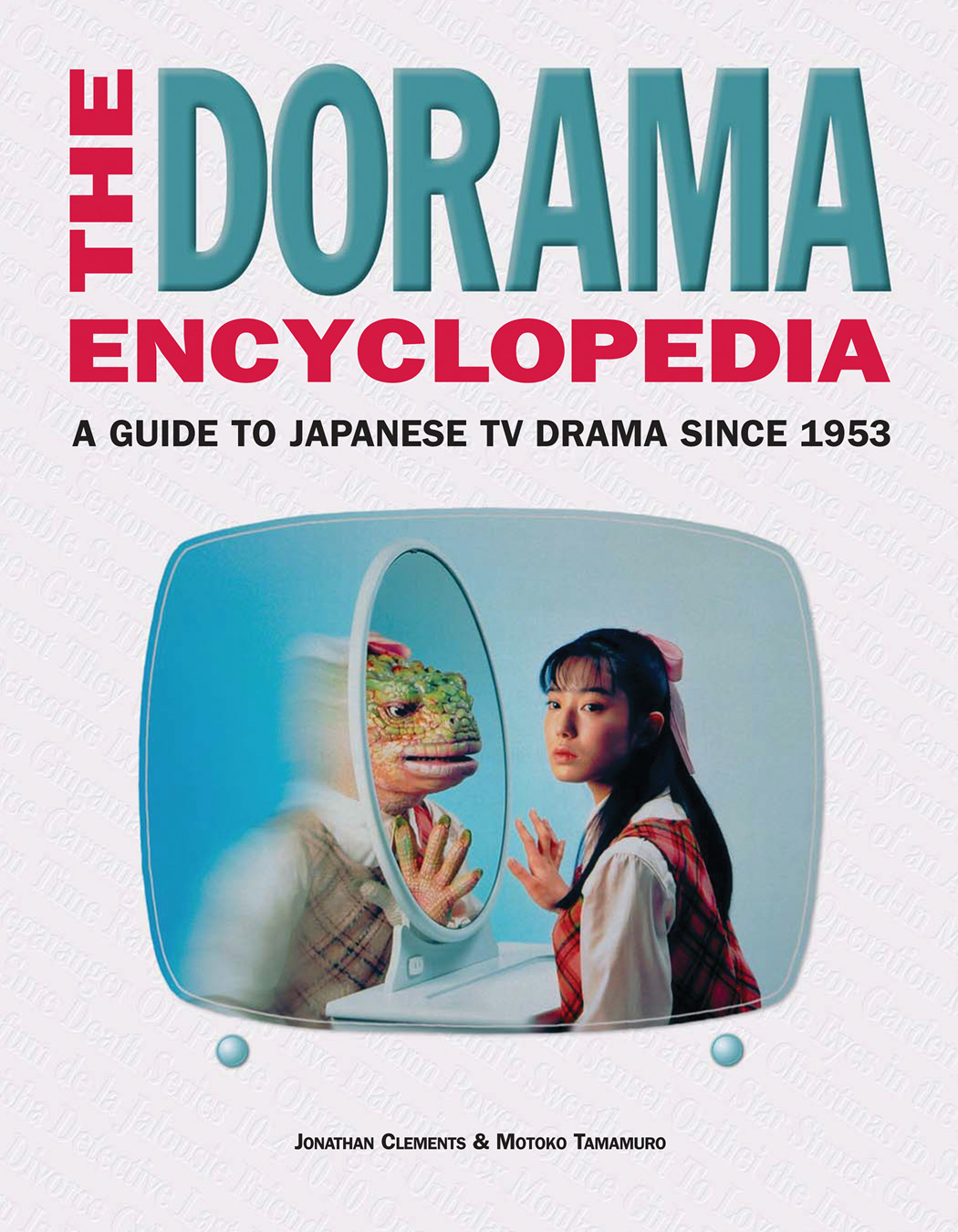

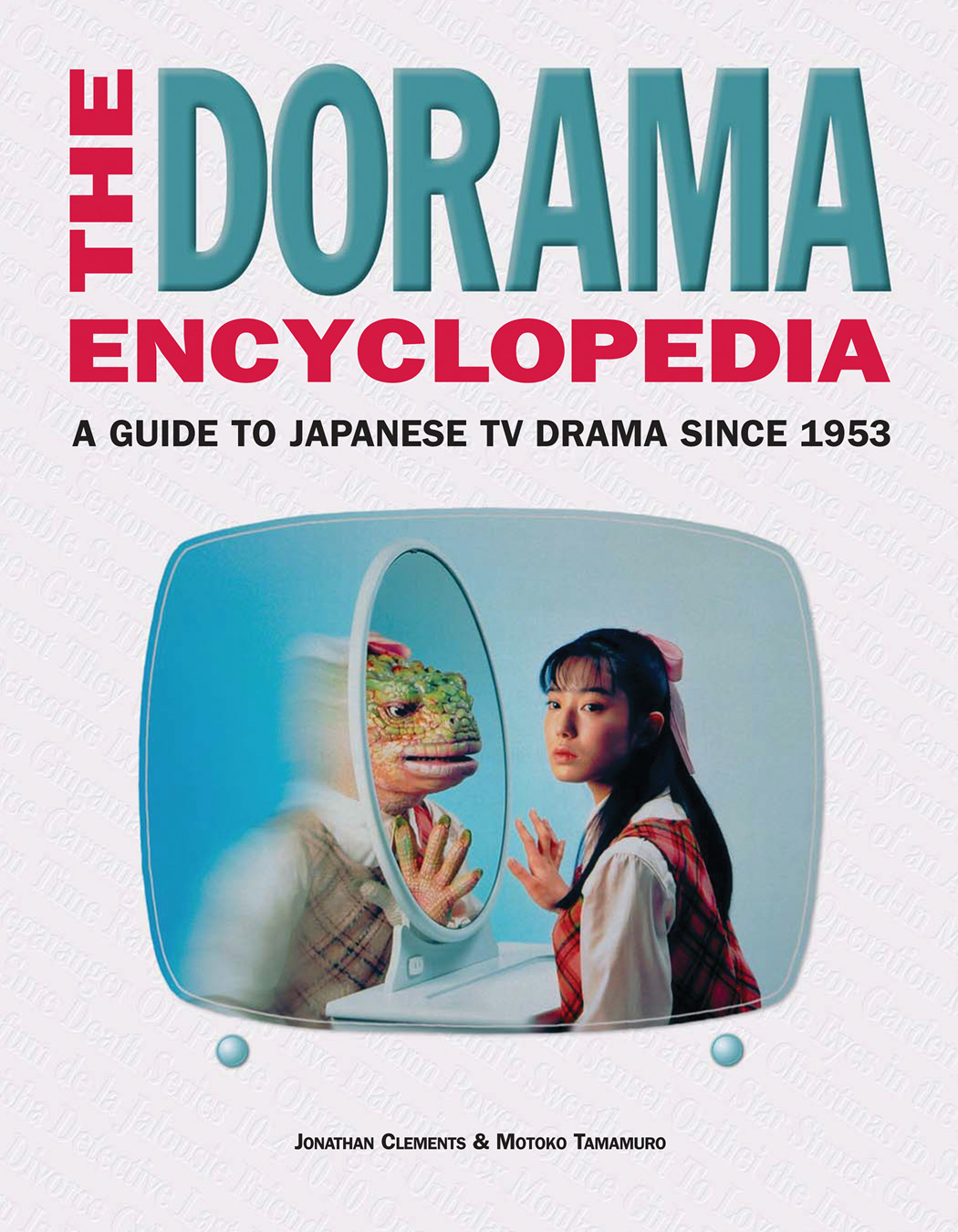

THE DORAMA ENCYCLOPEDIA

A Guide to Japanese TV Drama since 1953

Jonathan Clements & Motoko Tamamuro

Stone Bridge Press Berkeley, California

Published by STONE BRIDGE PRESS

P. O. Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707

tel 510-524-8732 sbp@stonebridge.com www.stonebridge.com

We want to hear from you! Updates? Corrections? Comments? Please send all correspondence regarding this book to doramainfo@stonebridge.com .

Text 2003 Jonathan Clements and Motoko Tamamuro.

Credits and copyright notices accompany their images throughout. Every attempt has been made to identify and locate rightsholders and obtain permissions for copyrighted images used in this book. Any errors or omissions are inadvertent. Please contact us at doramainfo@stonebridge.com so that we can make corrections in subsequent printings.

Front cover image: Daughter of Iguana (Iguana no Musume). Asahi TV.All Rights Reserved.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Clements, Jonathan, 1971

The dorama encyclopedia : a guide to Japanese TV drama since 1953 /

Jonathan Clements & Motoko Tamamuro.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-880656-81-7

1. Television plays, Japanese--History and criticism--Encyclopedias.

2. Television programs--Japan--History--Encyclopedias. I. Tamamuro,

Motoko. II. Title.

PN1992.3.J3 C58 2003

791.456--dc22

2003018182

To Lee Brimmicombe-Wood

INTRODUCTION

The idea of television was first discussed at the end of the 19th century, when futurists imagined not only hearing words and music, but also seeing pictures transmitted from a distant source. The French artist and writer George du Maurier depicted the idea in 1879 in Punch magazine, showing a couple sitting in front of their fireplace, with a screen above the mantelpiece showing a tennis match. His concept is still prescient today, since it not only evokes the 21st centurys plasma widescreen giants, but also interactivity, as du Maurier envisaged the viewers communicating with the people onscreen.

By 1882, another Frenchman, Albert Robida, predicted that this as-yet uninvented device would be able to bring images of distant wars into a familys home, make it possible to learn from teachers far away, shop without leaving an armchair, and even, once the ladies of the house were safely tucked away, peruse gentlemens entertainment of a more salacious nature.

In 1884, the German Paul Nipkow invented the Nipkow disk, a rotating disc whose spiral perforations permitted light to scan back and forth across its target. Though the Nipkow disc and other mechanical patents were later supplanted by electronic devices, their appearance allowed others to experiment further with the moving image.

As radio technology spread throughout the world, it dragged speculation about television in its wake. Inspired by the same Punch cartoons that fired European and American inventors, Kenjir Takayanagi wrote of his hopes for the coming medium in 1924. He experimented with primitive broadcasting technology, and in 1926, Takayanagi was able to recreate a fuzzy image of the character I from the Japanese katakana syllabary. It was the first thing to appear on a TV screen in Japan.

A FALSE START

The Nippon Hs Kykai, Japan Broadcasting Corporation, or NHK, was formed in 1926 by the merging of three independent radio stations in Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka. Charged with being the voice of the Japanese government, NHK also began early experiments in television on 13 May 1939.

The first television drama to be broadcast in Japan was Before Dinner ( Ygemae, 1940), written by Uhei Ima, and directed by Tomokazu Sakamoto and Ryji Kawaguchi. A 12-minute short about a family evening, it features two children waiting for their mother to return home. While the daughter, Kimiko (Shihoko Seki) prepares dinner, the son, Atsushi (Kiyoshi Nonomura) reads about a bus crash in the newspaper and begins to fret about his mothers safety. Mother (Izumiko Hara) eventually returns safely, clutching a photograph, which both children assume is a potential marriage partner for the other. Instead, it turns out to be a memorial picture of their father, presumed dead in the war in China, adding a poignant dose of pathos to an otherwise everyday scene.

Few people, however, got to see Before Dinner, as television sets were not on sale to the Japanese public. Soon afterward, in June 1941, NHK suspended all television experiments in preparation for the coming war.

Defeat, occupation, and reconstruction meant that television did not reappear in Japan until the 1950s. World War II also halted most TV activity abroad, but the Allied victors were soon continuing their experiments. Regular network broadcasting began in earnest in both America and Britain in 1946, giving the TV industry of the English-speaking world a further five-year head start on its Japanese counterpart. This gap in development would prove to be crucially important in later years.

first steps

Just as the demilitarized Japanese manufacturing industry was steered into toys and consumer durables, the nascent new TV medium was urged to avoid controversy. Toward the end of the Occupation, the Japanese were encouraged to emulate American soap operas. NHK continued its experiments, making another test broadcast with the light comedy Newly Wed Album ( Shinkon Album, 1952). NHKs TV arm was established in a licensing model after the fashion of the British Broadcasting Corporation, funded through subscriptions paid by TV set owners. However, there was already competition among other companies for the right to begin commercial broadcastingin other words, a TV station that gained its financing from sponsorship and advertising. The first to acquire a license was Nihon TV (NTV), an affiliate of the Yomiuri Shinbun newspaper, but NHK was still ahead in development. Consequently, the first official TV broadcast to the people of Japan was an NHK production on 1 February 1953. At the time, Japan had only 866 television sets that could receive it.

This first true broadcast was a nod to dramatic traditionAct IV Scene I of the famous kabuki play Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees. It features Shizuka, the mistress of Yoshitsune , as she walks with a shape-shifting fox, who protects both her and the drum she carries, which was made from his parents hides.

Just three days later, NHK showed a drama that had been specially commissioned for the screen, not lifted from another medium Flute on the Mountain Path ( Yamaji no Fue ), written by Kayoko Sugi and directed by Tsuneo Hatanaka. Based on a northern Japanese folktale, it depicted a sad love story between musician Tjir (Tsutomu Shitamoto) and his wife/guardian angel (Michiko tsuka). With limited resources, the drama had to be broadcast live, leading to Japanese TVs first blooper, when a cameraman mistakenly left the camera pointing at tsuka during one of her costume changes.

Other programming in the early days attempted to find subjects that could be exploited by the limited broadcasting resources of the day. Deals were struck with radio stations to have cameras present at news bulletins and musical performances, essentially adding little but a visual gimmick to programming already available on the radio. Sports, however, proved to be a far better use of the new medium, particularly if it was something like wrestling, boxing, or sumo, where the competitors could be expected to spend most of their time in a small area that could be covered by a single locked-off camera. With their Yomiuri Group affiliations, NTV soon began covering baseball in great detail, particularly the exploits of the Yomiuri Giants team.