Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Elizabeth

On the second day after the Red Army invaded Germany, we saw eight hundred Soviet children walking eastwards on the road, the column stretching for many kilometres. Some soldiers and officers were standing by the road, peering into their faces intently and silently. They were fathers looking for their children who had been taken to Germany. One colonel had been standing there for several hours, upright, stern, with a dark, gloomy face. He went back to his car in the dusk: He hadnt found his son.

Vasily Grossman, A Writer at War: A Soviet Journalist with the Red Army, 19411945

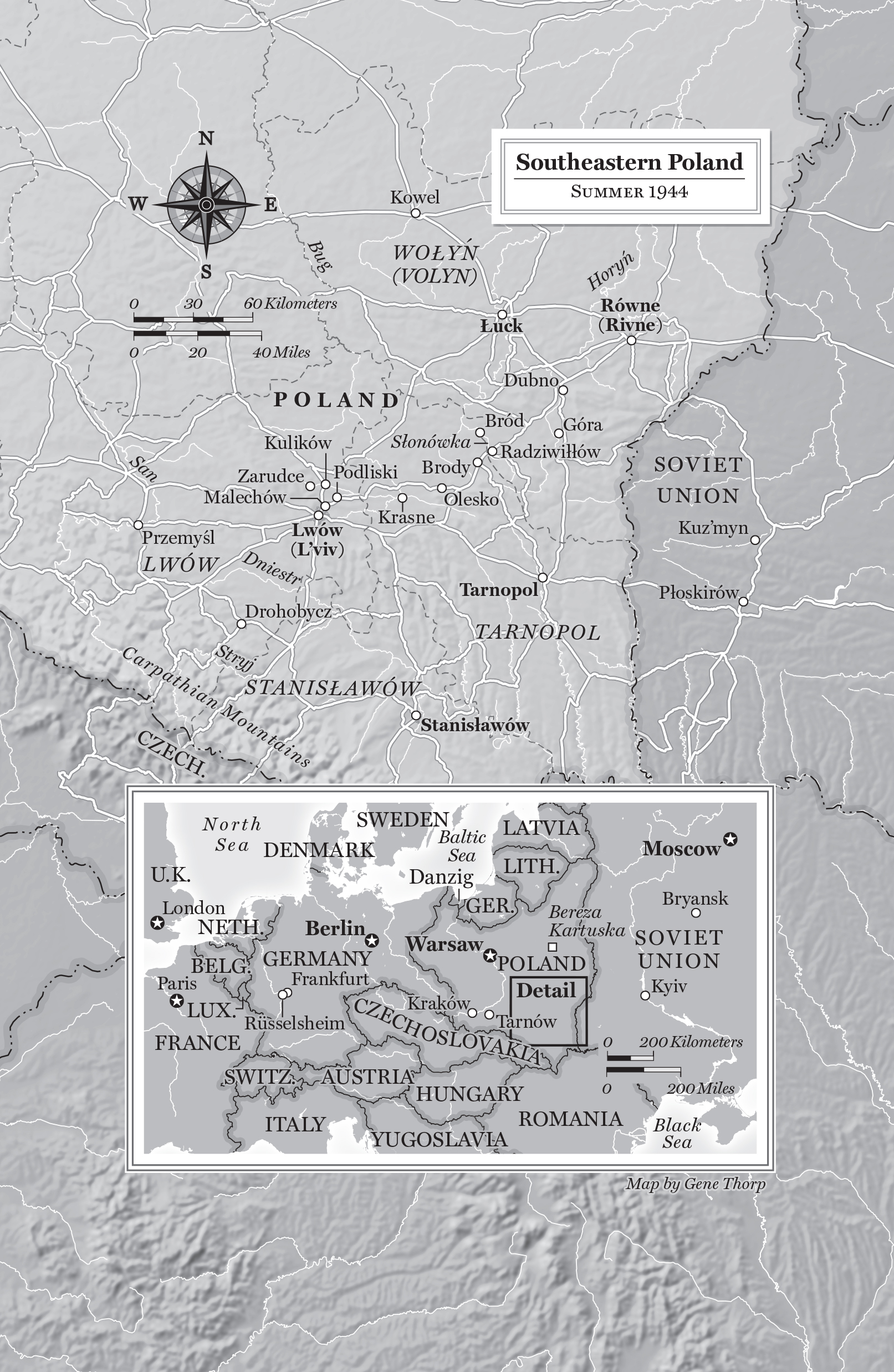

By late July 1944, the war in Europe has been raging for nearly five years.

German forces are being pushed back on both fronts. Britain and the United States have gained a foothold in France. The Soviet Red Army, with the help of the Polish Resistance, is advancing through Poland.

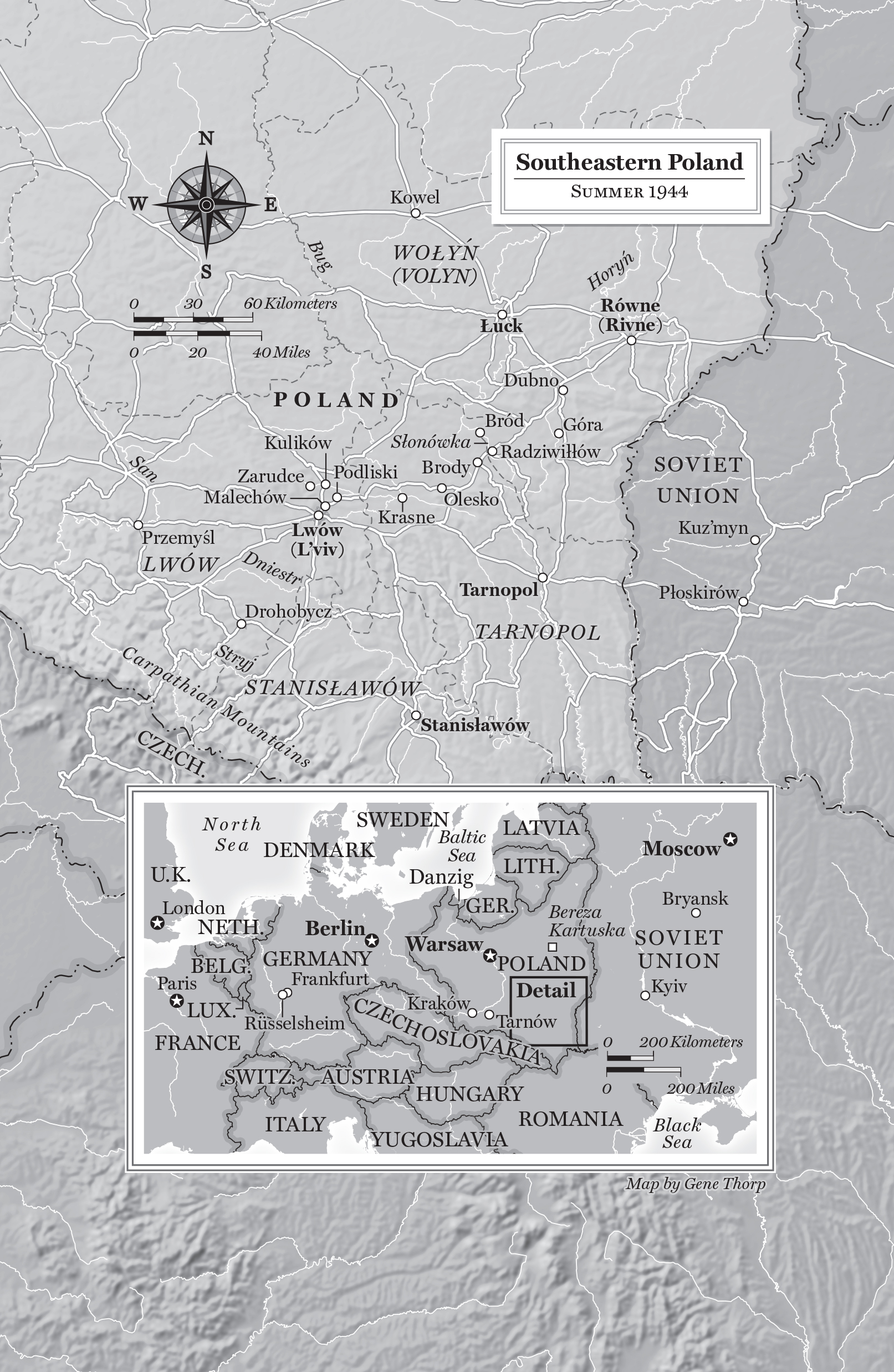

As the Germans retreat west, the Soviets move to consolidate power in Poland, already anticipating a new postwar order of Soviet control over Eastern Europe. They start disarming and arresting Polish Resistance soldiers. At the same time, they begin a brutal campaign against the UPA, Ukrainian nationalist partisans attempting to carve out an independent Ukraine from Polands disputed southeastern borderlands.

The Polish Resistance and the UPA have fought each other bitterly and bloodily through the years of German occupation. Historic grievances and injustices have become excuses for atrocities. Civilians have suffered the brunt of it. Tens of thousands have diedPolish civilians in massacres by the UPA, Ukrainian civilians in targeted reprisals by the Resistance. Now both sides, Polish and Ukrainian, face the prospect of another long occupation, another long war against another oppressive regime.

Both sides look to the western Allies for help against the Soviets once Germany is finally defeated. But western help is months awayif it comes at all.

Neither can afford to wait that long.

And neither can hope to win this war alone.

THE

SILENT

UNSEEN

LWW, POLAND

FRIDAY, JULY 28, 1944

Somebody had shot a political officer.

At leastI thought. My Russian wasnt anything at all to be proud of. But I had been handcuffed to this chair in this office listening to the junior officer out at the front desk shout into a telephone for over an hour, and I was pretty sure that was what he was saying between expletives: Somebody murdered a zampolit last nightyes, murdershot twice from behind at close range.

The culprit seemed to be one of their own men, which meant it wasnt me. I doubted I would be here, sitting relatively comfortably in this office, if they thought it was me.

My pistol, the Walther they took off me when they arrested me this morning, sat on the desk in front of me, pointing at me accusingly. It was half the reason I was herecarrying a weapon without authorizationand I guessed it was in here as evidence. It was the only thing I was carrying, which was the other half of the reason. I didnt have any papers. I had a perfectly valid excuse, but so far nobody had been interested in listening to it. Everybody had just assumed I was Polish Resistancea courier, perhaps, and apparently stupid enough to blunder right into a Soviet patrol.

The problem was I didnt know how to prove I wasnt. I knew enough about Soviet justice to know you were guilty until proven innocent. Sometimes even then.

The desk belonged to Comrade Colonel F. Volkov, 64th Rifle Division, NKVD. There was a nameplate. There were also two photographs in framesI didnt know of what; they werent facing meand a fountain pen in a holder, all precisely arranged. The drab green papered walls were empty, though you could see the odd dark spot here and there where previous occupants had hung things. They were still clearing out this place from the German occupation. Lww had been in Soviet hands for all of twenty-four hours. The dust hadnt even settled.

Somebody shut the office door behind me, muffling the sound of the ongoing telephone call.

Comrade Colonel F. Volkov came around the desk, unbuttoning his coat. He folded the coat neatly over the back of his chair, laid his briefcase on the desk, and set his smart blue cap beside it just so. Then he sat down facing me. He didnt look at me yet. He opened his briefcase and took out a piece of papermy arrest report, I presumedand spent a minute reading it in silence.

I knew how these things worked. I could guarantee you he had already read it. This part was just for show. But I wasnt complaining. It gave me a chance to size him up. I would put him at thirty-five or forty, prematurely gray, handsome in a stiff, austere sort of wayabsolutely unremarkable to all appearances, but I knew better. You didnt get to be comrade colonel of the NKVD by being unremarkable.

Maria Kamiska, he read aloud.

Da.

You may speak in Polish, he said disinterestedly, not looking up. Tell me if I need to make any corrections. Polish national, sixteen years old, resident of Brd, arrested for unauthorized possession of a weapon. He eyed the pistol just briefly. It was a German pistol, the Walther, which I assumed was doubly suspicious. No identification.

YesI mean, no corrections.

Where is Brd?

I didnt blame him for having to ask. There were about thirty-seven little villages called Brd in Poland. Brd just meant river ford. It was the sort of name I would make up if I were a spy or something.

On the Sonwka River in Woy Province, I told him. Ten kilometers from Radziwiw. Four days walk east of here. I didnt have a map, but I had divided the distance up by days on the big map in the train station back in Tarnw.

I couldnt tell whether the names meant anything to him. His face was expressionless. Why are you in Lww?

I wasnt, technically. They had arrested me on the road west of the city. But I didnt think Because your men brought me here was the answer he was looking for.

Im just trying to go home, I said.

Home from where?

Rsselsheimin Germany. The Opel automobile plant there. I was

Ostarbeiter. Taken for slave labor. He looked up for the first time. There was something almost hungry in the way his eyes searched over my face. You escaped?

During the bombing. There was an air raidthe Americans. The overseers left our barracks unguarded while they were in the bomb shelters. I started running.

Youve come from Rsselsheim on foot? He sounded more surprised than suspicious.

Just from Tarnw. Thats where the rail lines stopped. I hopped trains from Frankfurt.

He took out his fountain pen and made a note in Russian in the margin of the paper. How long since you were taken?

Two and a half years.

The pen paused.