Copyright 2022 by Elena Conis

Cover design by Pete Garceau

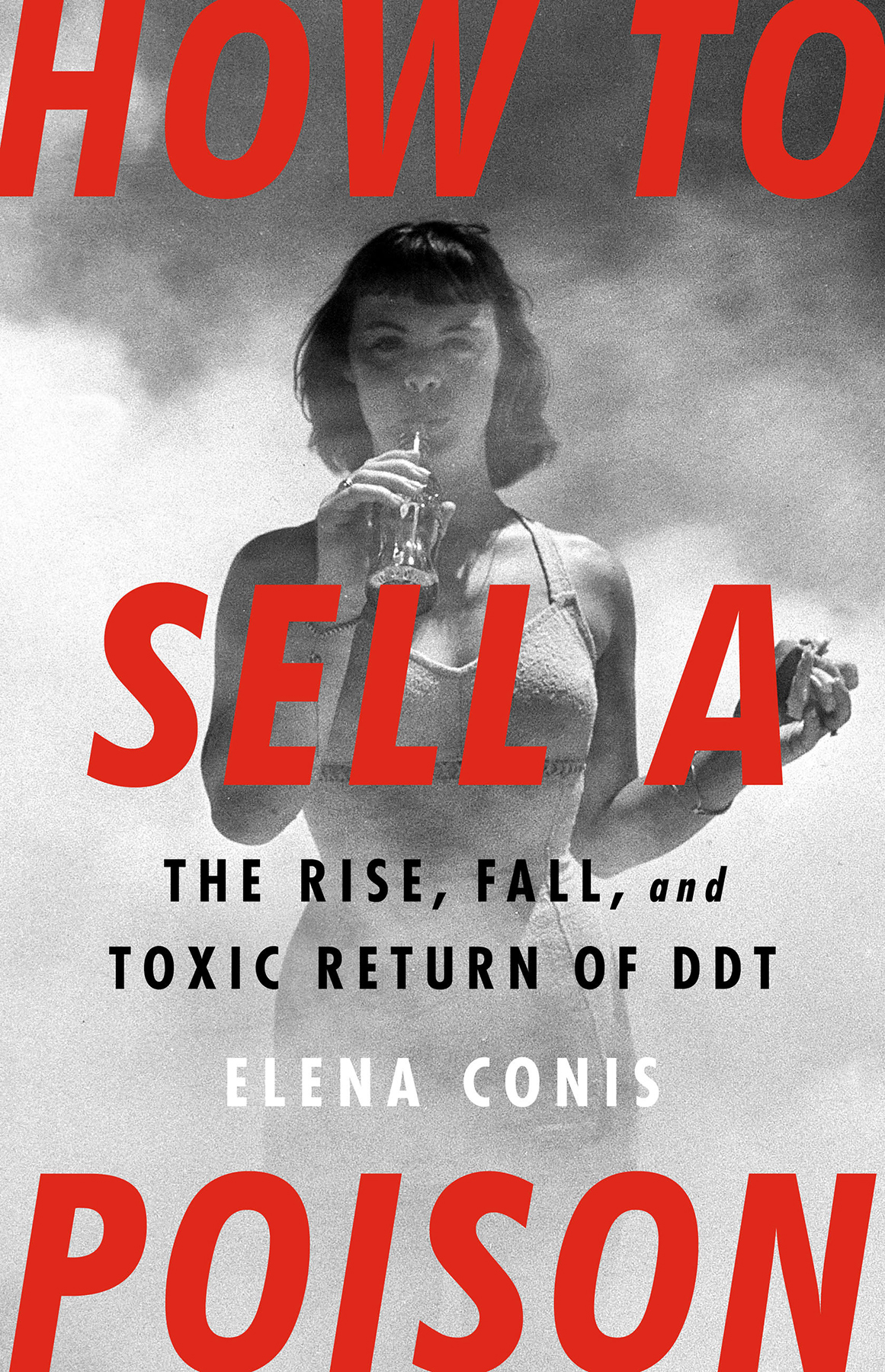

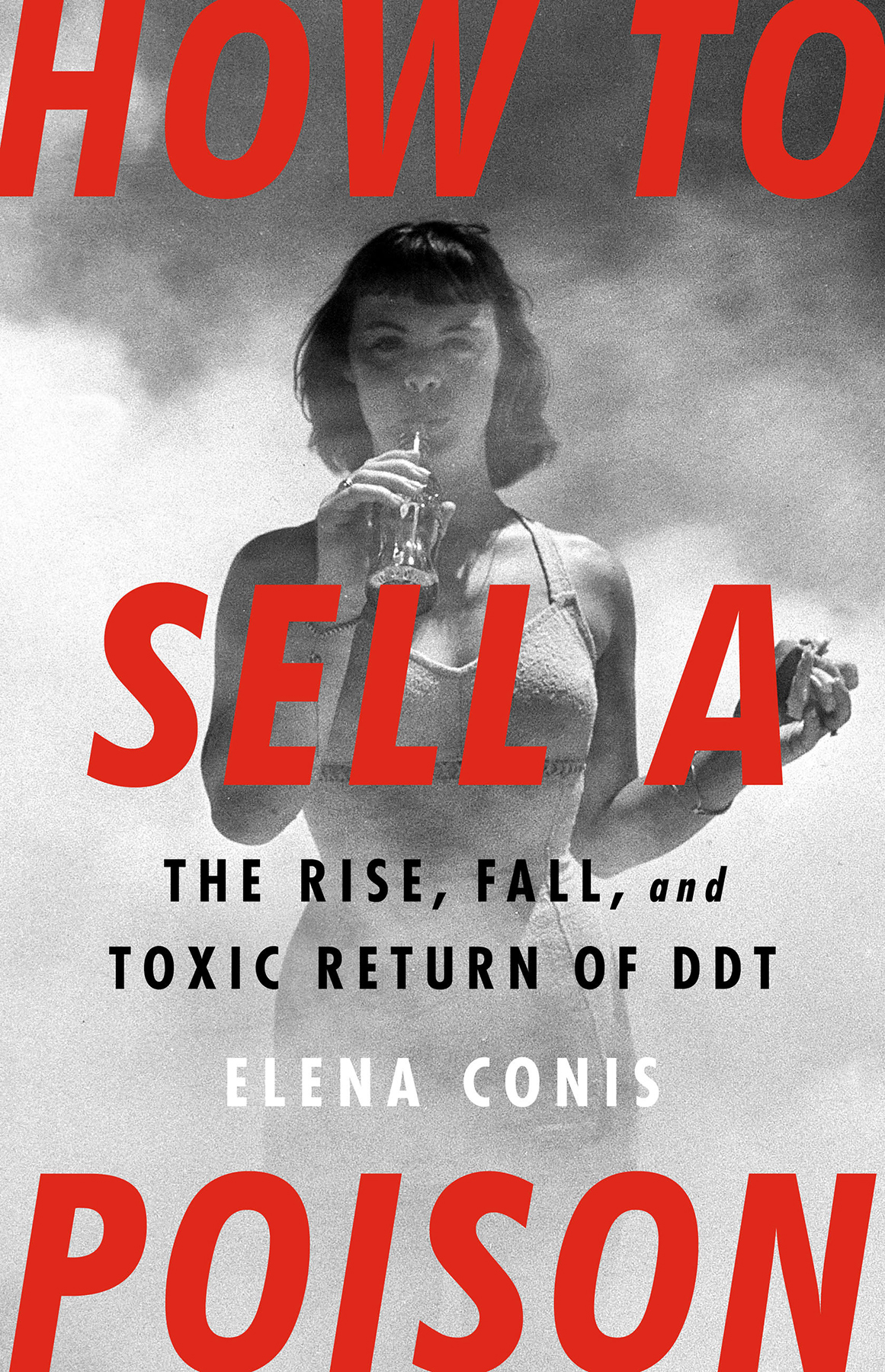

Cover photograph of woman standing in DDT spray George Silk/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Bold Type Books

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10003

www.boldtypebooks.org

@BoldTypeBooks

First Edition: April 2022

Published by Bold Type Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Bold Type Books is a co-publishing venture of the Type Media Center and Perseus Books.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Conis, Elena, author.

Title: How to sell a poison : the rise, fall, and toxic return of DDT / Elena Conis.

Description: First edition. | New York : Bold Type Books, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021047425 | ISBN 9781645036746 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781645036753 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: DDT (Insecticide)Toxicology. | DDT (Insecticide)Health aspects. | DDT (Insecticide)Environmental aspects. | DDT (Insecticide)Physiological effect.

Classification: LCC RA1242.D35 C65 2022 | DDC 632/.9517dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021047425

ISBNs: 9781645036746 (hardcover), 9781645036753 (ebook)

E3-20220309-JV-NF-ORI

For my family

In the summer of 1944 Robert Mizell was leafing through Time magazine when an article in the Science section caught his eye: censorship had just been lifted on one of World War IIs top-secret discoveries, a chemical called DDT.

At first glance, DDT sounded mundane. It killed bugs. Flies, bedbugs, moths, roaches, dog fleas, potato beetles, cabbage worms, fruit worms, corn borers, mosquitoes, their larvae, and more. But a US Army official said that by killing mosquitoes, DDT promised to wipe out malaria. He claimed it would revolutionize medicine as much as the discovery of antiseptics had revolutionized surgery. Mizell, a top administrator at a university in Atlanta, clipped the article and underlined the bit about malaria. He attached a note and sent it to an old college friend, Robert Woodruff, the soft-drink magnate who ran Coca-Cola.

If the stuff is as good as reported, have you thought about the tremendous economic implications? wrote Mizell, who often advised his friend on business and charitable matters. Maybe we should buy some cheap land. Say nothing about it. In the chemical he saw gold: ranches, housing developments, vacation resorts, and golf courses going in where mosquitoes and flies once thrived. Many like him did. A journalist for Life magazine reported that where US troops were stationed in the South Pacific, DDT had proved that it could easily convert a verminous hellhole of an island into a health resort.

When the war was over, DDT came home a hero. It entered a booming postwar consumer marketplace, where it became the solution to a long list of postwar problems. Farmers sprayed it on orchards, vineyards, and croplands and dipped whole herds of cattle in it. Developers erected new suburbs using DDT-coated plywood. Home owners moved in and decorated with DDT-slicked wallpaper. They sprayed kitchens to kill ants and roaches, dusted mattresses to kill bedbugs, and treated pets to kill fleas. Dry cleaners added DDT to their cleaning solutions to ward off moths. Hotel and restaurant decorators arranged bouquets of DDT-impregnated fake flowers to repel wasps and bees. City officials sent out cavalcades of DDT spray trucks to clear neighborhood streets of insects, and children ran behind them, playing in the mist.

In just a few short years, the pesticidea relatively simple compound of carbon, hydrogen, and chlorine, used with abandonhad come to symbolize our postwar nations capacity to vanquish age-old scourges with modern science and technology.

Three decades later, it was banned.

The 1972 bantechnically a regulatory restriction of DDTs approved usesfollowed years of mounting protest boosted by a nature writer named Rachel Carson. Her 1962 book Silent Spring implicated all of the new postwar pesticides, DDT included, in an epic attack on American wildlife. DDT was a neurotoxin with a predilection for fat tissue and a tendency to stick around, or persist, long after it had been sprayed. It killed beneficial bugs, fish, and birds. Carson also speculated that its broad class of chemicals, the synthetic postwar pesticides, was responsible for the nations rising number of cancer cases. But she was mostly concerned with what DDT had come to symbolize to her: the nations rush to embrace quick-fix technologies without taking the time to learn about their unintended consequences, especially those that werent immediately apparent. Following high-profile hearings held by the nations brand-new Environmental Protection Agency, DDT left the market with as much fanfare as it had arrived.

Then, a generation later, a seemingly grassroots movement rose up to call for DDTs return. DDTs defenders argued that the chemical was the best tool against malaria, which was resurgent in sub-Saharan Africa. They also argued that its harms had been gravely overstated. Rachel Carson was wrong, they said. It was time to bring back DDT.

That didnt happen, but when more than a hundred nations signed an international treaty in 2001 to phase out another class of chemicals to which DDT belonged, the persistent organic (that is, carbon-based) pollutants, they did carve out an exception for the chemical. DDT, the signatories agreed, was critical for public health, even if it was known to be toxic.

Thats DDTs story in three neat acts: war hero turned pariah turned exception. For a historian of medicine like me, its a familiar story; its one Ive shared with students many times. But the third act always nagged at me. Why was the late 1990s the moment when Americans suddenly started calling for DDTs return? A few years ago I decided to try to figure that out. In a handful of emails and letters in a collection of corporate documents, I found an unexpected answer.

In the late 1990s, public relations specialists for Philip Morristhe tobacco companywere compiling a list of the centurys most important and inspiring women as part of a stealth campaign to promote Virginia Slims cigarettes. Rachel Carson was on the list for her groundbreaking work exposing the dangers of pesticides such as DDT. At the same time, however, Philip Morris executives were funding an entirely separate campaign, one to bring back DDT.

The tobacco industry had no interest in selling the pesticide, of course; it was trying to sell cigarettes. But it found DDTs story to be a helpful scientific parable, one that, told just right, illustrated the problem of government regulation of private industry gone wrong. DDT, in this tale, never should have been banned in the first place. Companies, not liberal activists and politicians, should be trusted to make responsible choices. DDTs fate showed what happened when government got in the way. To sell one poison, in short, the tobacco industry sold a morality tale about another.