BANNED

BANNED

A History of Pesticides

and the Science of Toxicology

Frederick Rowe Davis

Published with assistance from the

foundation established in memory of

Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class

of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2014 by Frederick Rowe Davis.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in

whole or in part, including illustrations, in

any form (beyond that copying permitted

by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S.

Copyright Law and except by reviewers

for the public press), without written

permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be

purchased in quantity for educational,

business, or promotional use. For

information, please e-mail

(U.S. office)

or (U.K. office).

Set in Galliard with Poetica Display type

by Westchester Book Group.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN: 978-0-300-20517-6 (cloth)

Library of Congress Control Number:

2014944393

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of

ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my parents

Dan Clifford Davis

and

Judith Rowe Davis

When the public protests, confronted with

some obvious evidence of damaging results

of pesticide applications, it is fed little

tranquilizing pills of half truth. We urgently

need an end to these false assurances, to the

sugar coating of unpalatable facts. It is the

public that is being asked to assume the risks

that the insect controllers calculate. The

public must decide whether it wishes to

continue on the present road, and it can do

so only when in full possession of the facts.

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1.

Toxicology Emerges in Public Health Crises

CHAPTER 2.

DDT and Environmental Toxicology

CHAPTER 3.

The University of Chicago Toxicity Laboratory

CHAPTER 4.

The Toxicity of Organophosphate Chemicals

CHAPTER 5.

Whats the Risk? Legislators and Scientists Evaluate Pesticides

CHAPTER 6.

Rereading Silent Spring

CHAPTER 7.

Pesticides and Toxicology after the DDT Ban

CHAPTER 8.

Roads Taken

PREFACE

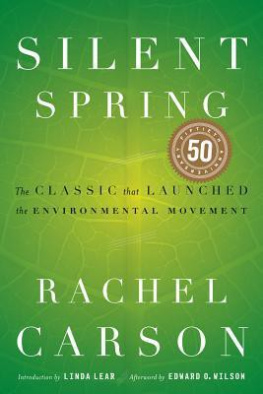

Late in 1972, William Ruckelshaus, administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, announced that he was canceling the registration for DDT, in effect banning the use in the United States of one of the most popular insecticides available since its introduction after World War II. Environmentalists hailed the ban on DDT as a crowning achievement of the American environmental movement and the culmination of a decade of activism that had coalesced in the wake of the publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson in 1962. Carsons damning critique of the indiscriminate use of chemical pesticides and the resulting widespread ecological contamination in the United States captured the hearts and minds of Americans as few other books had, and it inspired extensive hearings in the Presidents Science Advisory Committee and Congress. The passage of the National Environmental Protection Act in 1970 and the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that same year signaled to Americans that their concerns had been heard. The DDT ban terminated applications of one of the most notorious and environmentally destructive chemicals in America. Could there be a more perfect conclusion to a dark chapter in the story of American agriculture and public health?

In May 1982, several bird-watching friends (retirees) invited me to join them near Rochester, New York, to find as many bird species as we could in a single day. The big day started at about 1:00 a.m. as we headed out to find nocturnal owls and nighthawks. By 4:30, we had arrived at Norway Road, a renowned hotspot for migrating birds west of Rochester. In the early morning darkness, we heard an American woodcock, and just before dawn a veery began singing its ethereal song and a wood thrush soon joined in. By daybreak, dozens of other speciesneotropical migrantscould be heard: warblers, vireos, thrushes, tanagers, cuckoos, flycatchers, and sparrows. The phrase dawn chorus fails to capture the deafening cacophony of thousands of birds in full breeding song. My ears were still ringing when I arrived back home near midnight. Even as a teenaged birder I knew that I had witnessed something special that morning. It did not occur to me that I would never again hear anything like the dawn chorus I heard on the May morning so long ago.

Fast-forward thirty years to March 12, 2013, the New York Times reported on a study revealing that acutely toxic pesticides correlated to declines in grassland birds in the United States more closely than habitat loss through agricultural intensification. Three days later, a federal judge considered a motion to dismiss a 2011 lawsuit in which the Center for Biological Diversity and the Pesticide Action Network alleged that the EPA has allowed pesticide use without required consultations with federal agencies. What is going on here? More than fifty years after the publication of Silent Spring and forty years after the ban on DDT, pesticides still account for widespread deaths in birds and other wildlife. Could it be that Carsons statement in the epigraph applies to the risks of pesticides today? My purpose in writing Banned is to explain one the great ironies of the American environmental movement.

Writing this book emerged out of a simple objective. I had read Rachel Carsons Silent Spring, and I wanted to explore her scientific and medical sources in building the case against DDT. As I originally understood the story, Silent Spring was a significant catalyst in the environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s as well as in the banning of DDT. But I soon discovered that Carson began researching pesticides in earnest during the late 1950s, at a time when American scientists, legislators, and regulators were debating the risks and benefits of the still-new chemicals as they revised existing laws. Moreover, concerns about chemical exposures had much deeper roots that significantly predated this period.

Inspired by the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Carsons book, Banned examines the development of synthetic pesticides and the science of toxicology over the course of the twentieth century, as well as the legislation that governs exposures to these chemicalsfrom the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 to the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 and beyond. By studying the larger context of the evolution of pesticides and toxicology, in this book I reveal how environmental science and policy evolved across the twentieth century. Carson published Silent Spring at a critical moment in the history of environmental science. Studying her sources and rereading her careful interpretations of science deepens our appreciation of the achievement of Silent Spring. But an analysis of pesticides policy and usage patterns in the decades following the ban on DDT exposes a tragic irony in the worldwide proliferation of the organophosphate pesticides, chemicals that Carson and the toxicologists acknowledged to be far more toxic to wildlife and humans alike.

Next page