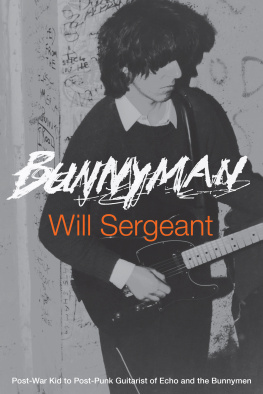

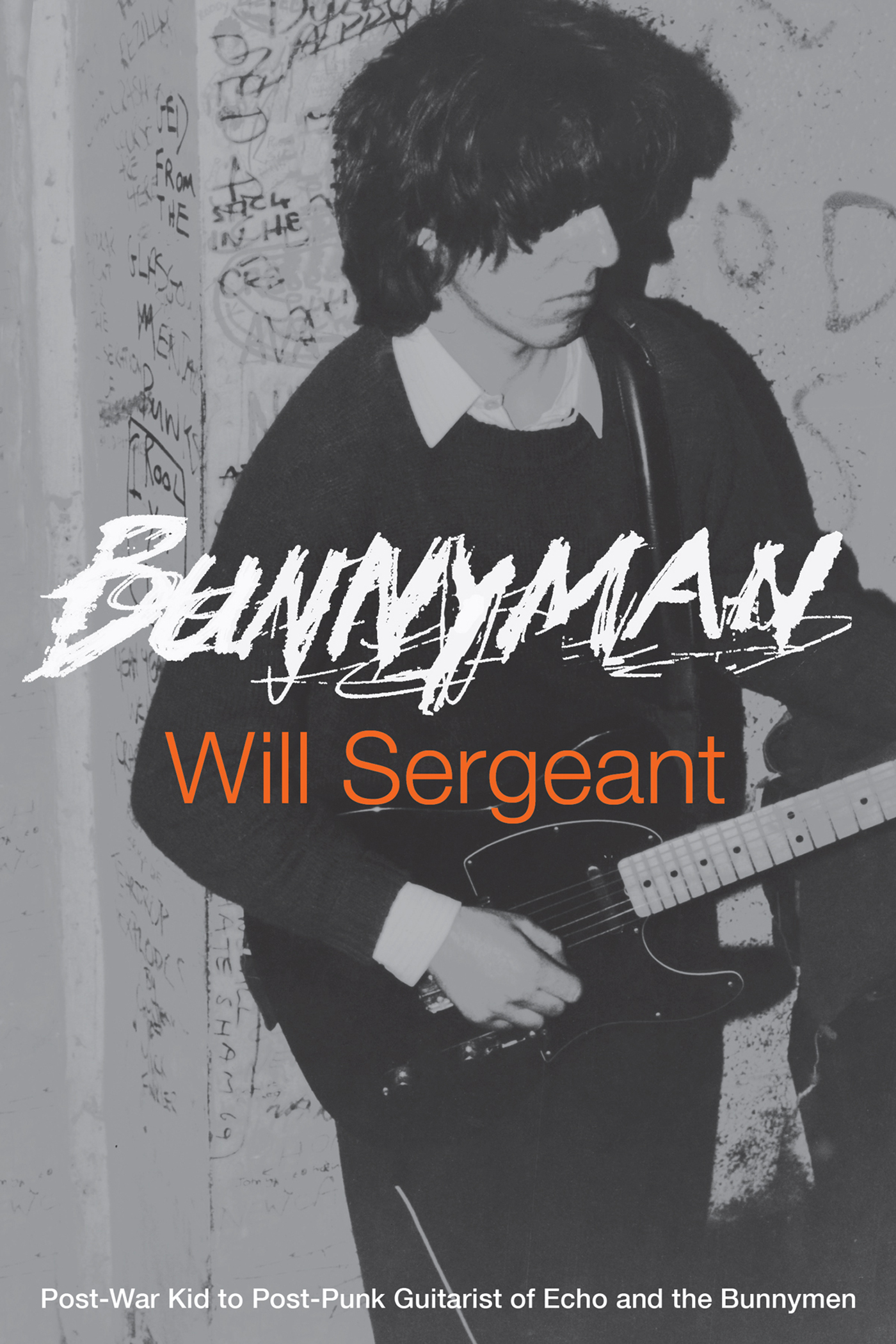

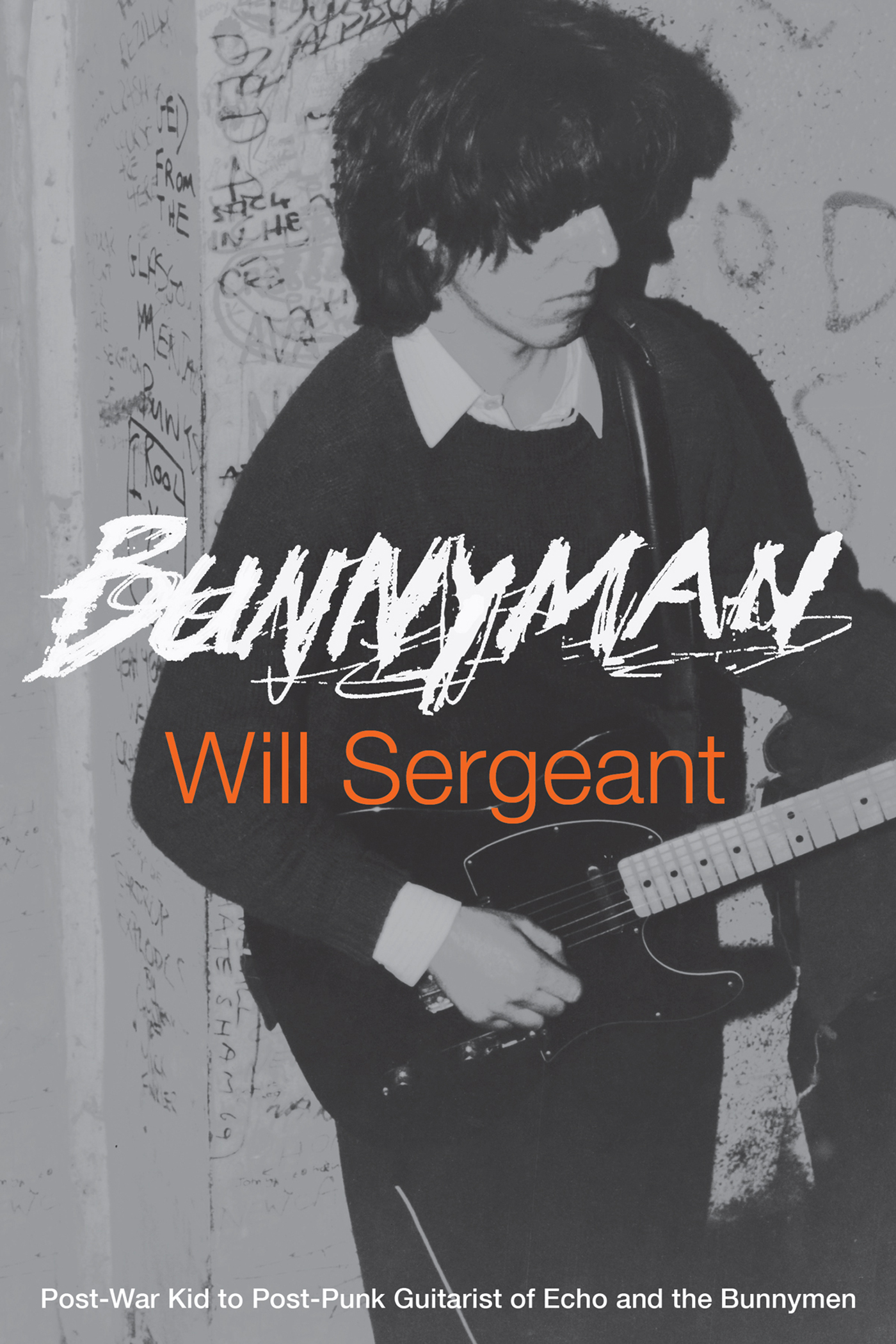

Bunnyman

BUNNYMAN

Post-War Kid to Post-Punk Guitarist of Echo and the Bunnymen

Will Sergeant

https://www.thirdmanbooks.com/bunnymanbook

password: bunnyman

Bunnyman: Post-War Kid to Post-Punk Guitarist of Echo and the Bunnymen

Copyright 2021 by Will Sergeant

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

For more information:

Third Man Books, LLC, 623 7th Ave S.

Nashville, Tennessee 37203

A CIP record is on file with the Library of Congress.

FIRST USA EDITION

ISBN 9781734842289

Cover design and collage by Will Sergeant

Additional layout by Jordan Williams and Maddy Underwood

Front and back cover photos by Mick Finkler

To my girls: Paula, Alice & Greta

Contents

Station Road in the 1960s.

1.

Fried Beans

Tequila The Champs

I am William Alfred Sergeant aka Will Sergeant aka Sgt Fuzz. This is my story from the beginning.

The Sergeants that is mum Olive, dad Alf, sister Carole, brother Steven and me all lived on the council estate on Station Road in the heart of the village of Melling. The houses on Station Road were built five years after the end of the Second World War. A massive building drive was in full swing; the new government, led by the reinstated war leader Winston Churchill, was rebuilding its way to a new future, after the six years of horror the European continent had just lived and died through.

Our family moved to Station Road in 1952. I am reliably informed by my sister that we were the first family to be housed on the road. It seems my grandfather Tom Sergeant who was a Justice of the Peace and a rural district councillor was not averse to using his power to help his own family out. A crafty push up the council house waiting list got the Sergeants a new three-bedroom semi-detached, complete with front and back garden. They are solid houses, built of a brown brick. These bricks were used in the construction of a lot of northern council houses of this period. Im not sure how a brand-new sturdy house can become so shitty in such a short period, but by the time I was aware of these things, I knew our house was a bit of a dump. I do not think we were poor compared to others in the street. The truly poor were called povos, a slang word for poverty stricken or skint.

Though Melling is only eight miles from the city centre of Liverpool, it was still far enough away for us locals to be called woolly backs, a derogatory term connoting an intimate relationship with a farm animal. It never bothered me much; I like being a woolly back. At least it wasnt the old classic sheep shagger, a term generally reserved for real rural folk.

I always think of Melling as the place where Liverpools sprawl ends and the countryside begins. In Liverpool, the perception of Melling was that it was posh. Well, it might have been in some parts but not Station Road. We were the scum, the ruffians from the council estate. To be fair, there was a high proportion of nutjobs, criminals, wife beaters, drunkards and thugs and that was just in our house.

Even though Melling felt very rural, there was a great big factory right in the middle of the village: the BICC. This stood for British Insulated Callenders Cables. They made all sizes of electrical cables. Lorries or wagons as they were called back then would constantly be leaving the gates of the BICC transporting these massive reels of wire all over the world. It seemed that most people in the village worked at the BICC, including many of my friends mums and dads. The factory gave the village its own distinctive smell a heady scent best described as a cross between burning plastic and Napalm, with a hint of liquorice. Not unpleasant, and almost comforting. God knows what those noxious fumes were doing to our pristine young lungs. Probably not that much, considering everyone smoked non-stop at that time: Senior Service, Capstan Full Strength and good old Woodbines, or Woodies as they were more commonly known. Ciggies would be in the gobs or sandwiched between yellow-stained fingers of just about every man, woman and child you came across. Not much time was spent worrying about what this passive smoke was doing to the kids.

The village is carved up by the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. This exciting waterway was a playground for all the local children. It was always fun messing about down there, though it was only about three to five feet deep; a death trap by todays standards, but this was a health-and-safety free time. Kids would jump off bridges into the brown water. The canal was home to discarded barbed wire, old beds, bikes and general junk. The classic shopping trolley had not turned up at this point, simply because we had no supermarkets to nick them from. Its surprising that nobody got killed or injured. We would fish for tiddlers sticklebacks with nets on the end of bamboo poles. We would generally muck about clambering across swing bridges or making rafts.

Among the flotsam and jetsam of the canal, the occasional dead dog would float by. Back in the 1960s, dead or even still living old dogs would be best disposed of in the canal. Alsatians mainly would appear, their backs bald and blistered by the sun. These were possibly scrapyard guard dogs, too old, arthritic and well past their growl-by date. The sad and rotting beasts, bloated with gas, floated high, bobbed in among the weeds, caught by the wind sailing alongside the towpath, flyblown ears drooping and sad. They made challenging targets for a canal-side scallywag like me, armed with a brick (you had to make your own entertainment in the olden days). Even stuffing unwanted puppies or kittens in a sack and then chucking them into the canal was normal behaviour for some of the more nasty postwar adults. I am guessing that seeing people blown up in the Liverpool Blitz, witnessing death and destruction all around Europe in the not-too-distant past, hardens you up a little.

Liverpool had the shit kicked out of it by the Germans and bore many scars of the devastation. The bombed out St Lukes Church at the top of Bold Street is a permanent reminder of those grim days, still standing roofless and pocked with bites taken out of the stone by shrapnel. The city was once an architectural jewel in the empire, but now was left as rubble, peppered with bombsites. Plenty of those wastelands were still about well into the 1980s.

My mum, Olive, in the late 40s.

My mum Olive told me of a time when, as just a teenager, shed been caught out by a bombing raid before she could get to the air-raid shelter in Walton. Walton is pretty much next to the docks at Bootle. Bootle was and still is one of Britains main ports, a prime target for the Luftwaffe, the German air force. Mum was rushing to get to the shelter instructed by an ARP (Air Raid Precautions) warden, on his head a shiny black helmet bearing a white W painted on the front. The warden was cycling along and clearing the streets of people. A bomb fell and exploded very close, sending flames and shrapnel all over the street. My mum witnessed the wardens head getting cleanly blown off his shoulders. The black helmet with the neat W stencilled on the front spun into the air and landed with a clatter on the ground. The wardens legs peddled on for one or two rotations, then the bike fell to the cobbles. Mum ran as fast as she could into the relative safety of the shelter.

Next page