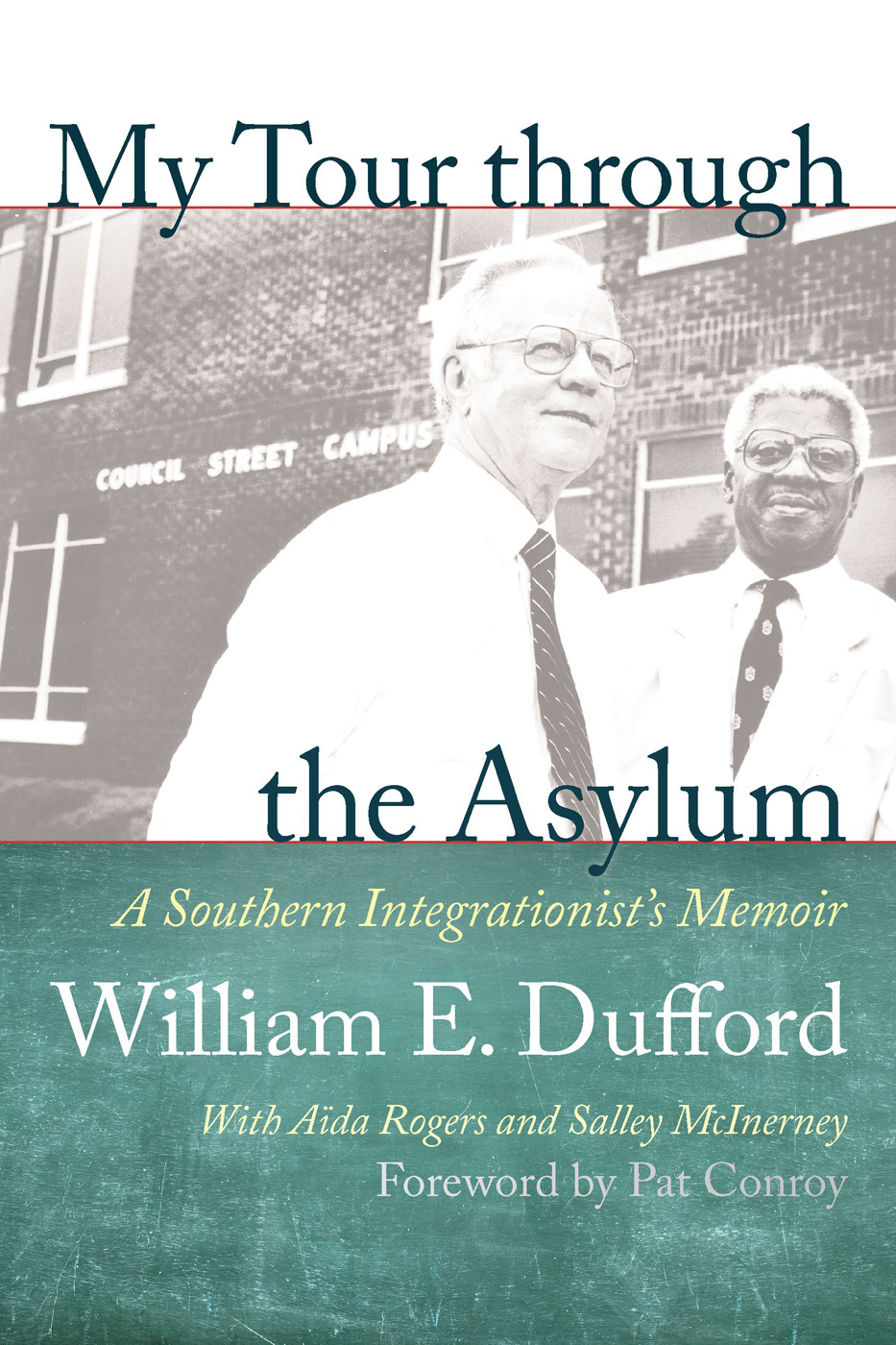

My Tour through the Asylum

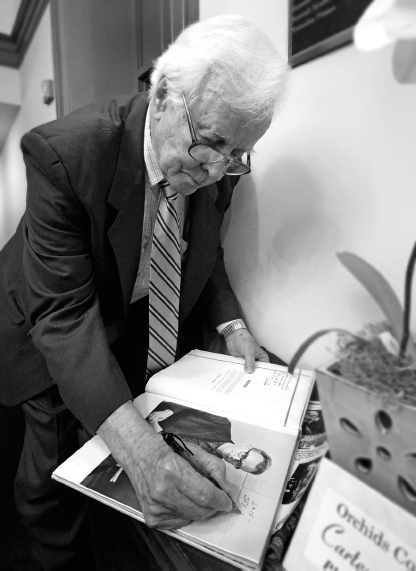

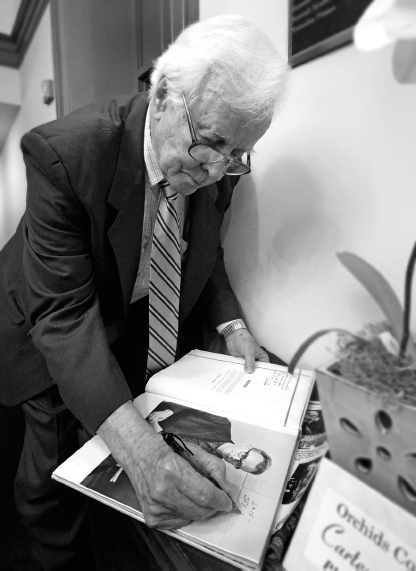

Bill Dufford signs a copy of the 1961 Beaufortonian yearbook at the Newberry Opera House on May 11, 2015, the night he was presented with the Order of the Palmetto, South Carolinas highest civilian honor. Photograph by Ted Williams, courtesy of the Newberry Opera House.

My Tour through the Asylum

A SOUTHERN INTEGRATIONISTS MEMOIR

William E. Dufford

With Ada Rogers and Salley McInerney

Foreword by Pat Conroy

The University of South Carolina Press

Publication is made possible in part by the

generous support of the William E. Dufford Fund

for Civil and Social Justice Publications.

2017 William E. Dufford

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/

ISBN 978-1-61117-896-8 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-61117-897-5 (ebook)

FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPHS: Bill Dufford with Dr. Earl Vaughn, principal of Lincoln High School in Sumter, South Carolina, in 1969, courtesy of the authors collection

South Carolina is too small for a republic and too large for an insane asylum.

James L. Petrigru to Benjamin F. Perry, December 8, 1860 From McPherson, Drawn with the Sword

RECORD RAINS, 2015

Jeff Greene, friend and former student of William E. Dufford

Last night, I called you to check in about the floods

and assuage my guilt at not being in touchnews

of record rains saturating your town nearly drowning me.

Your voice held the rising water at arms length,

that calm equanimity that had once rescued me

its own force of nature.

I never learned to swim properly, thrashing

through the alien water, a spastic amid

agile amphibians. It wasnt a natural disaster,

like the flood filling your basement

with things that swim and bacterial

mud from the Saluda and the Broad.

I asked how you were and you told me

of your gratitude, reminded me that so long ago,

I had taken care of you.

When the floodwaters recede, a new world is

visible, a baptism by disaster.

Oh! I must go back to the water

now that I can swim with such grace

and know who has been saved.

Contents

PAT CONROY |

SALLEY MCINERNEY |

WILLIAM E. DUFFORD |

ADA ROGERS |

WILLIAM E DUFFORD |

ADA ROGERS AND SALLEY MCINERNEY |

Illustrations

following page 64

following page 146

Acknowledgments

C OUNTLESS THANKS go to the many former students, colleagues, and friends who lent their own recollections to this project, to Pat Conroy for his gracious foreword (first presented as an introduction at the South Carolina Governors Awards in the Humanities induction ceremony), to Tim Conroy and Jeff Greene for their early readings of the manuscript and to Greene as well for his poem Record Rains, to Ada Rogers and Salley McInerney for their remarkable efforts in researching and telling a life story some ninety years in the making, and to the University of South Carolina Press and its former director, Jonathan Haupt, for preserving and sharing that story in the hopes that it might help chronicle our past and light the way to a brighter futuretogether, as one people.

Foreword

The Summer I Met My First Great Man

PAT CONROY

I N THE SUMMER OF 1961, when I was a fifteen-year-old boy, I was lucky to have the great Bill Dufford walk into my life. I had spent my whole childhood taught by nuns and priests and there was nothing priestly about the passionate, articulate man William E. Dufford who met me in the front office of Beaufort High School dressed in a sport shirt, khaki pants, and comfortable shoes in a year that history was about to explode in the world of South Carolina education circles. Because he did not wear a white collar or carry a long rosary on his habit, I had no idea that I was meeting the principal of my new high school. In my mind, I thought as I saw him moving with ease and confidence in the principals main office that day that he must have been a head janitor in the relaxed, unCatholic atmosphere of my first day at an American public school. It was also my first encounter with a great man.

I was a watchful boy and was in the middle of a childhood being raised by a father I didnt admire. In a desperate way, I needed the guidance of someone who could show me another way of becoming a man. It was sometime during that year when I decided I would become the kind of man that Bill Dufford was born to be. I wanted to be the type of man that a whole town could respect and honor and fall in love withthe way Beaufort did when Bill Dufford came to town to teach and shape and turn their children into the best citizens they could be.

Bill gave me a job as a groundskeeper at Beaufort High School that summer between my junior and senior years of high school. He had me moving wheelbarrows full of dirt from one end of campus to another. He had me plant grass, shrubs, trees, and he looked at every patch of bare earth as a personal insult to his part of the planet. At lunch, he took me to Harrys Restaurant every day and I watched him as he greeted the movers and shakers of that beautiful town beside the Beaufort River. He taught me, by example, how a leader conducts himself, how the principal of a high school conducts himself, as he made his way from table to table, calling everyone by their first names. He made friendliness an art form. He represented the highest ideals of what I thought a southern gentleman could be. He accepted the great regard of his fellow townsmen as though that were part of his job description. That summer, I decided to try to turn myself into a man exactly like Bill Dufford. He made me want to be a teacher, convinced me that there was no higher calling on earth and none with richer rewards and none more valuable in the making of a society I would be proud to be a part of. I wanted the people of Beaufort, or any town I lived in, to light up when they saw me coming down the street. I was one of a thousand kids who came under the influence of our magnificent principal, Bill Dufford. For him, we all tried to make the world a finer and kinder place to be.

Bill Dufford was raised in Newberry, in the apartheid South, where the civil rights movement was but a whisper gathering into the storm that would break over the South with all of its righteousness and power. Though Bill had been brought up in a segregated society, he charged to embrace the coming of freedom to southern black men and women with a passionate intensity that strikes a note of awe and wonder in me today. He went south to the University of Florida in 1966, four years after I graduated from high school, and there he came under the influence of some of the greatest educational theorists of his time. He returned to South Carolina with a fiery commitment to the integration movement in his native state. No other white voice spoke with his singular power. He headed up the school desegregation department, which sent people into all the counties in the state to help with the great social change of his time. I know of no white southerner who spoke with his eloquence about the great necessity for the peaceful integration of the schools in this state. What I had called greatness when I first saw him in high school had transfigured itself into a courage that knew no backing down, to a heroism that defied the ironclad social laws of his own privileged station from a great Newberry family.

Next page