Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lembersky, Yelena, author. | Lembersky, Galina, author.

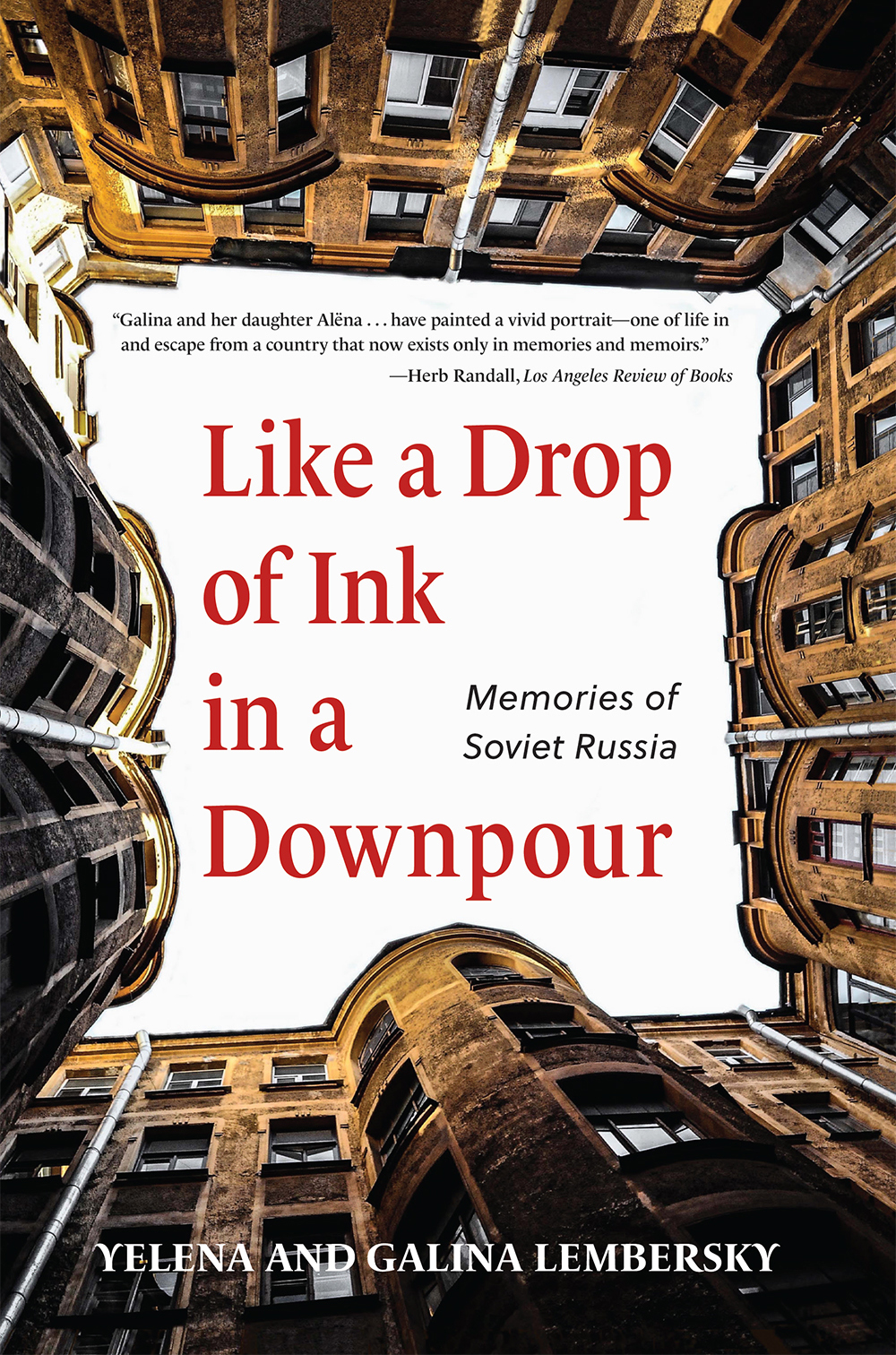

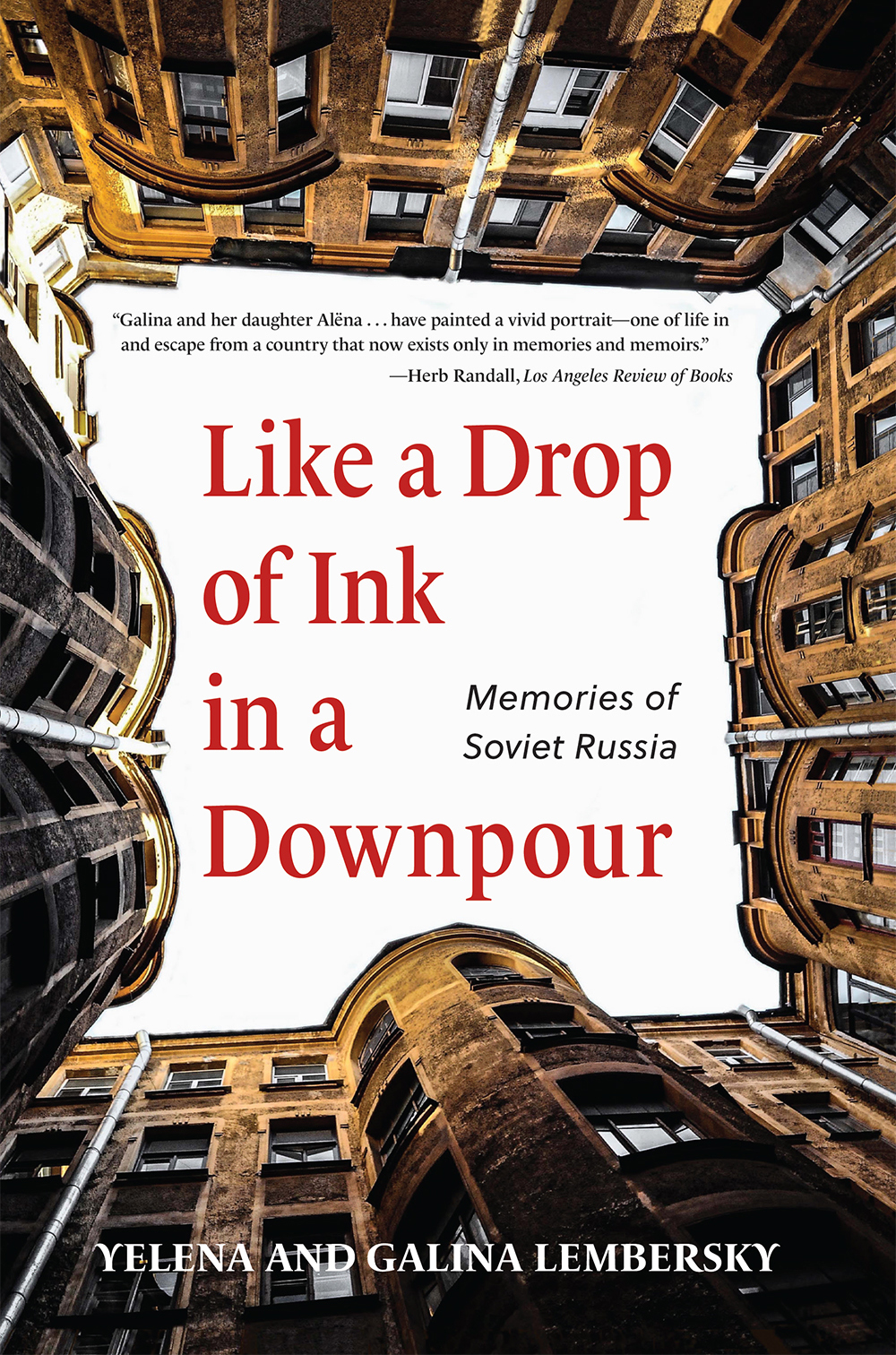

Title: Like a drop of ink in a downpour : memories of Soviet Russia / Yelena Lembersky and Galina Lembersky.

Description: Boston : Cherry Orchard Books, 2022.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021034748 (print) | LCCN 2021034749 (ebook) | ISBN 9781644696699 (paperback) | ISBN 9781644696705 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781644696712 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Lembersky, Galina. | Lembersky, Yelena. | Soviet Union--Biography. | Women--Soviet Union--Biography. | Jews--Soviet Union--Biography. | Artists--Soviet Union--Biography. | Russian Americans--Biography. | Prisoners--Soviet Union--Biography.

Classification: LCC DK37.2 .L46 2022 (print) | LCC DK37.2 (ebook) | DDC 947/.004924--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021034748

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021034749

Copyright 2022 Yelena Lembersky. All rights reserved.

ISBN 9781644696699 (paperback)

ISBN 9781644696705 (adobe pdf)

ISBN 9781644696712 (epub)

Book design by Grace Peirce

Cover design by Whitney Scharer

Published by Cherry Orchard Books, an imprint of Academic Studies Press

1577 Beacon Street

Brookline, MA 02446, USA

www.academicstudiespress.com

Praise for Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour

Like a Drop of Ink pulls readers into the raw realities faced by Jews who tried to emigrate from Soviet Russia. While focused on Leningrad in the 1970s and 80s, the account has new relevance today. The precise details, recalled from the separate viewpoints of a young daughter and her mother, are shocking but all too familiar for many. Reactions to the loss of their home, false imprisonment, anger, and stubborn ambition to survive are expressed with harsh and often poetic honesty. The profound influence of their father and grandfather, artist Felix Lembersky, his belief that art and integrity are crucial, is a constant and sustaining theme of their chronicle of life in limbo.

Alison Hilton, Wright Family Professor of Art History, Emerita, Georgetown University, author of Russian Folk Art

This is a profoundly powerful and poignant memoir, both significant and stunning . It combines an incomparable and sweeping overviewof a time and place of great horror and sometimes hope that remain completely unknown to those who did not live itwith an artists eye for intimate detail and a poets ear for metaphor and simile.

Ori Z. Soltes, Teaching Professor of Jewish Civilization, Georgetown University

A gripping memoir about outwaiting political injustice , outwaiting political anti-Semitism, and about the nonnegotiable price of winning. A miracleaccomplished in great measure by the understated love and loyalty, beautifully crafted and presented, between mother and daughter.

Rabbi Joseph Polak, author of After the Holocaust the Bells Still Ring

For Vitaliy and our children

Also by Yelena Lembersky

Felix Lembersky: Paintings and Drawings

Contents

Note on Names

Following are the names of the coauthors and their immediate family. Yelena and Galina Lemberskys names are followed by the nicknames or the diminutives by which they were known in Russia. All other people in the accountfriends, neighbors, coworkers, or prison inmatesare real, but some names have been changed.

Alna (pronounced Ale-yna), aka Alnushka, Alnka, Alshenka, Yelena Lembersky : daughter of Galia and narrator of Parts One and Three

Galia, Galka, Galina Lembersky : mother of Alna, daughter of Felix and Lucia Lembersky, and narrator of Part Two

Felix Lembersky (19131970): grandfather of Alna, father of Galia, husband of Lucia. A prominent artist born in Lublin, Poland, raised in Berdichev, Ukraine, educated at Kultur-Lige and the Art Institute in Kiev, and the Academy of Art in Leningrad

Lucia, Lucy, Lucinka Lembersky (19151994): wife of Felix Lembersky, mother of Galia, and grandmother of Alna

Mikhail Ksendzovsky : uncle of Lucia Lembersky. Singer, actor, and director of the Theater of Musical Comedy and the Summer Theater at Sad Otdikha in Petrograd-Leningrad in the 1910s and 20s

PART ONE

Alna

In the Woods

A KNOCK ON THE DOOR , a muffled, tentative thud. Not Mamas.

All that morning, September 15, 1981, I had walked holding my thumbs folded into my fistsa Russian superstition: hold your thumbs and think of someone to bring them good luck. Mama does it for me when I have a test at school or go onstage to read her favorite poem: Comrade Lenin, I report to younot a dictate of office, the hearts prompting alone. Vladimir Mayakovsky. The Soviet avant-garde. She taught me to recite it with feeling, raising my voice at The quotas for coal and for iron fulfill and then lowering it for But there is any amount of bleeding, muck and rubbish around us still.

She did not let me come with her to the trial. You dont need to see this circus.

Some had advised her to take the childfor leniency and the compassion of the jury.

Like hell they will have compassion, she said.

I watched from my window as she walked down the muddy footpath, stepping on islands of broken concrete. She went toward the Leninsky Avenue metro station and did not detour to Schastlivaya (Lucky) Street, even though I asked her to. Thats too bad, I thought. She turned around to face me and kept walking backward. Good luck! Good luck! I yelled out so she could hear me. And then, quietly, so that luck would fly to her like a swarm of bees, I waved to her hard, so I would feel pain in my wrists. Just in case.

I would recognize Mamas footsteps rap-a-tap with the echoing off the stairway, the loud smooch of her plum handbag against the door, her keys giggling inside it, playing hide-and-seek with her hands. The door would swing open and she would sail in on a blustering wind with plans and ideas, new assignments for me and a review of everything I had done in her absence.

This knock is not hers. I open the door. Its Zhenia. One of Mamas many work friends. Zhenia stands on our landing, thumbing her wrinkly purse, crossing and uncrossing her feet in short booties trimmed with a thin strip of fur. She can tip over standing like that, I think. Zhenia, once a schoolteacher, now a hairdresser. Standing before me, she is rustling in her mind through pages of textbooks on preteen psychology, readying for a difficult heart-to-heart conversation.

I cut her off. Should I get my things?

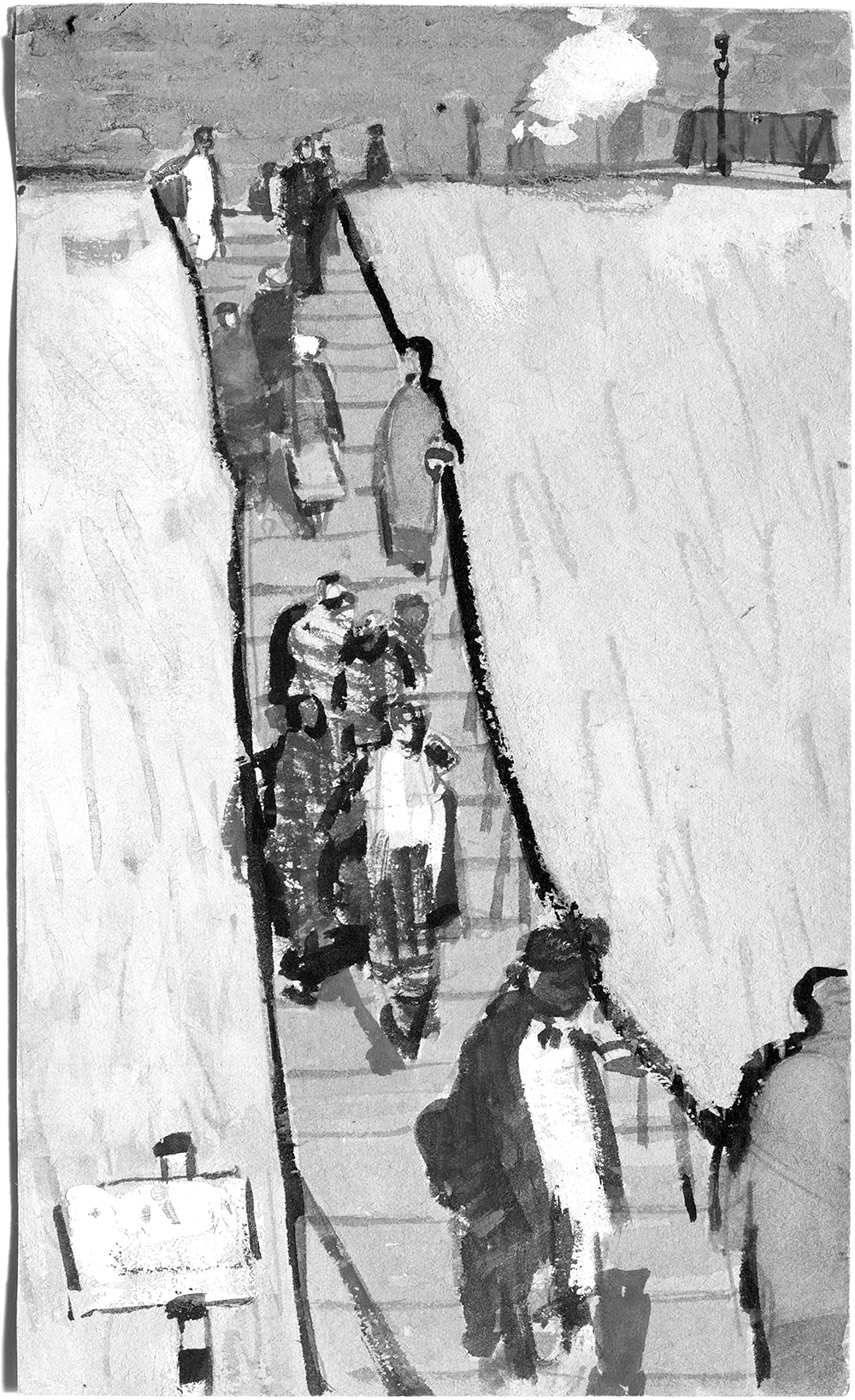

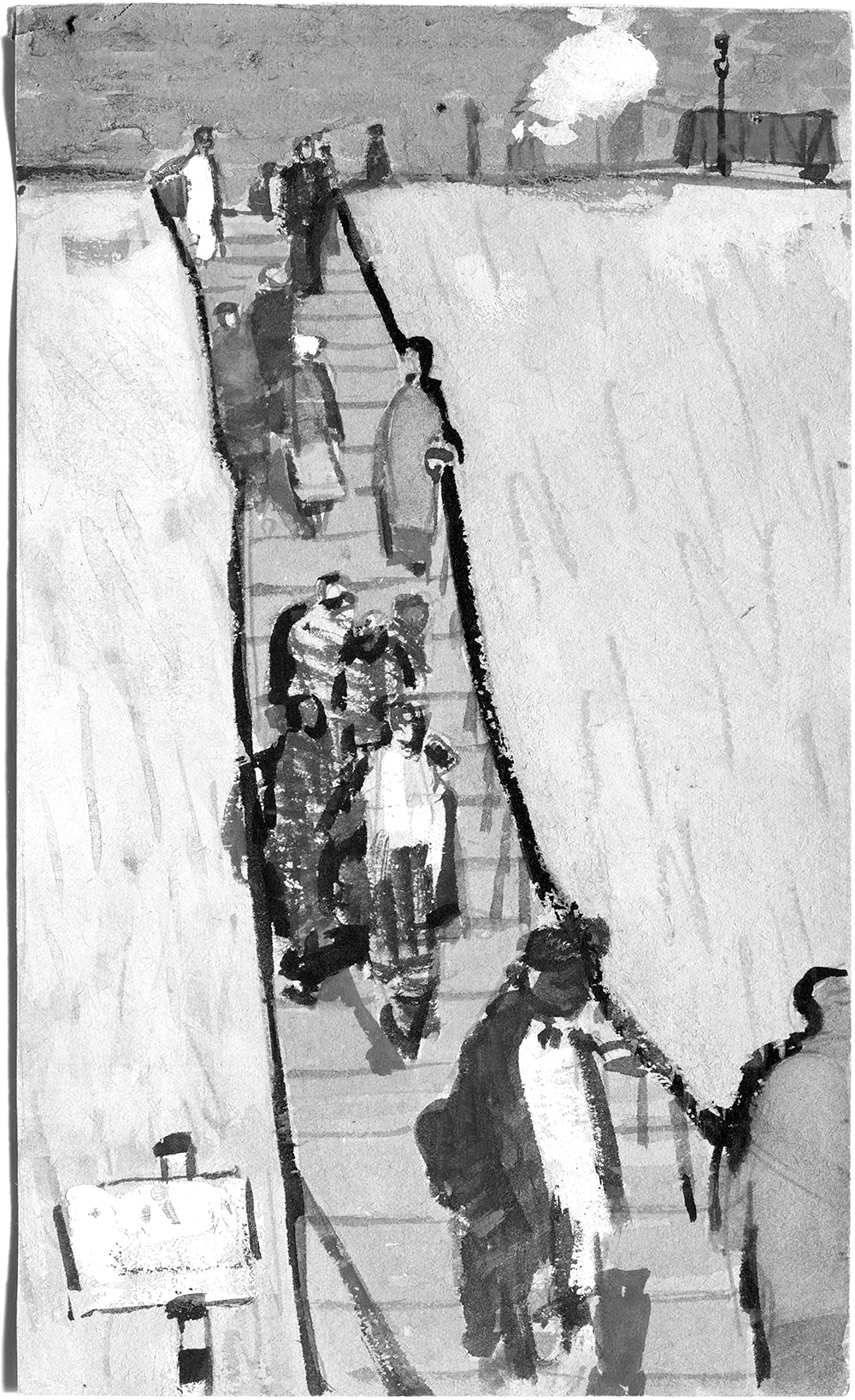

On our way to Zhenias home, she keeps looking at me sideways, waiting to see my eyes turn swollen and red. They wont. Not when we go down into the pit of the metro station with the stench of burned rubber. Not when we stand at the platform strewn with dirt and sawdust that a janitor mops up around our feet. Not when a train jolts and thrashes and we grip the handrails and the coats of passengers to stay upright. Not after we eat a dinner of hot dogs and mashed potatoes, and Zhenia makes up my bed, moving her son to a folding aluminum cot. She tells him, Alnas mother has gone away. Alna will stay with us until she comes back. I am not glad for her hospitality. It is not her fault.

Next page