First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2016

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

My job as principal has not only been to educate children, but also to protect them. While I have been completely truthful in this book about my experience starting a school in Brownsville, certain names and identifying biographical details have been changed (in one case, a composite character was created) in order to protect the identities of not only students but also family members and teachers.

PREFACE

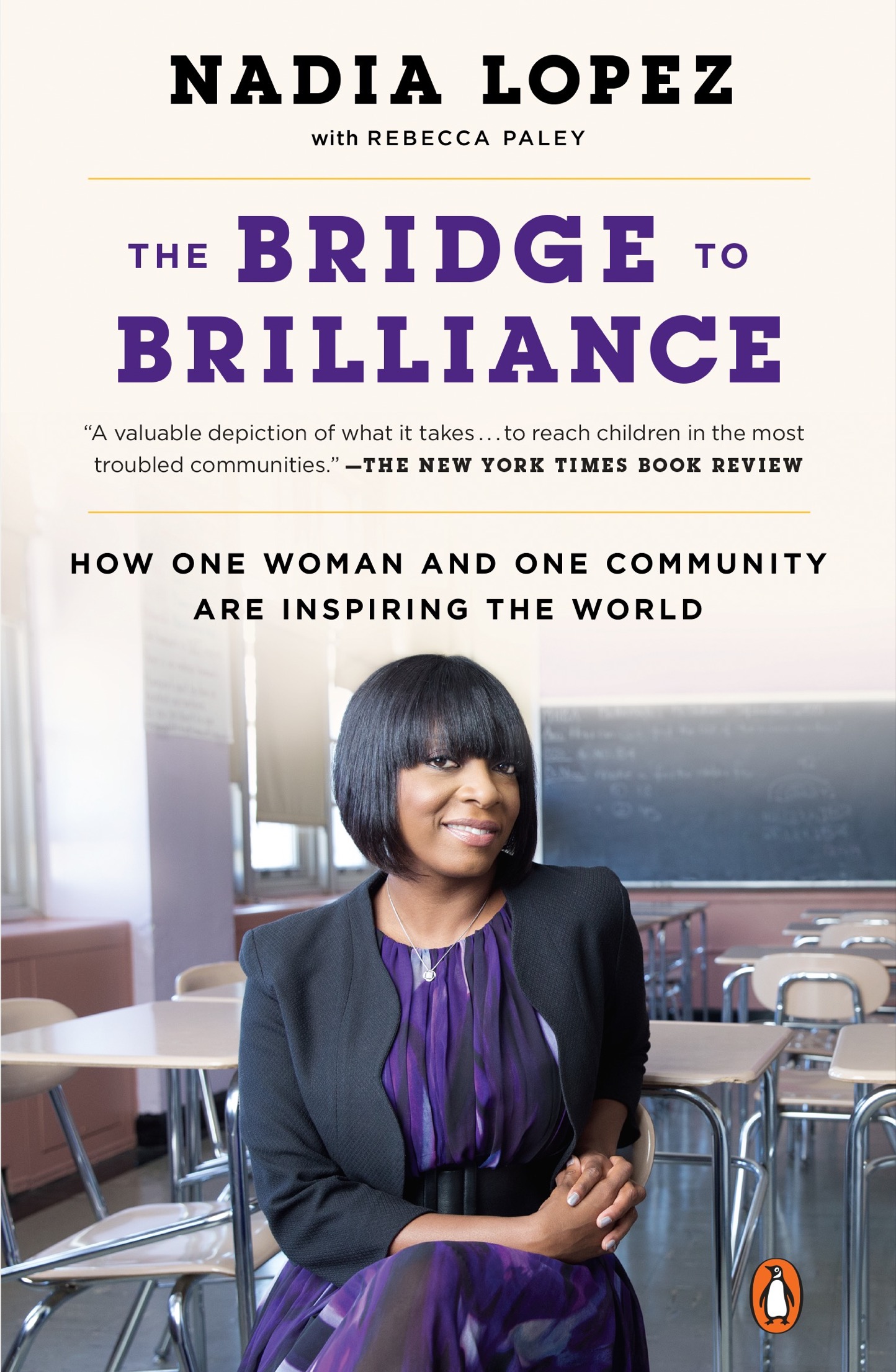

S itting at my desk, I contemplated all the paperwork that had piled up since my school, Mott Hall Bridges Academy, was thrust into the spotlight a few months before. A small public middle school in one of the poorest and most underserved neighborhoods of Brooklyn was an unlikely candidate for an international press sensation. But ever since one of my boys brought attention to Mott Hall through a comment he made on the popular blog Humans of New York, ordinary people around the world had been captivated by what I was trying to dowhich was simply to take care of kids everyone else seemed to want to forget.

I had barely started on the stack of performance reviews awaiting my attention when Malik walked in and sat down in one of the chairs across from my desk. The kids in this building know my door is open to them anytime.

I need to have a talk, the sixth grader said in such a soft voice I could hardly hear him.

Talk about what? I asked.

About me.

What about you?

My work.

What about it?

Its hard.

Okay, which classes are hard for you?

Every class. Except PE. Its too hard. Im failing. I always fail.

His problems had begun back in his elementary school when his fourth-grade teachers, who couldnt tolerate his angry demeanor, let him fall behind.

Malik, with chubby cheeks from baby fat hed soon lose and sad eyes that he kept downcast, was typical of a kid from a failing elementary school; he was two years older than most of the children in his grade because hed been held back a couple of times. The first thing people notice about him is that he looks like hes angryall the time. His expression makes it seem like he cant be bothered, like he doesnt want to hear what you have to say. That couldnt be further from the truth, but you would never know it unless you speak to him, which his expression keeps people from doing. I always tell my kids, You need to understand there are teachers in this world who, if they dont like you, have that power to derail you. Even if you dont feel like theyre invested, you cant stop doing your work. Because they will be fine with you failing and repeating the grade.

I understood how Maliks demeanor could deflate a whole room and how frustrating that might be for a teacher just trying to get through a curriculum that was necessary to prepare a class to take state exams. But it wasnt that he didnt care; he acted like he didnt care. Some teachers in his elementary school, however, took his negative behavior personally. Instead of supporting him and working with him until he understood the material, they just held him over. That started a trajectory from which it would be very hard for Malik to deviate.

Making kids repeat grades unfortunately is rarely about remediation and more about punishment. So when Malik came to us, not only did he still lack the academic skills he should have had by sixth grade but, as a thirteen-year-old in class with mostly eleven-year-olds, he was also disconnected from his peers. He would become agitated by how loud the other children in his class, who were at a different maturity and energy level, would get.

Dont mistake me, Malik was not innocent. Soon after he arrived at Mott Hall, he had to call his mother from my office because he was talking back to his teacher and arguing with his peers. He got on the phone and said, Yeah. So Im told I need to call you because, like, I was rude. Yeah. Uh-huh. Uh-huh. Yeah, aight. Then he hung up.

Who were you talking to? I asked.

My mother.

No, no. I know I told you to call your mother. But Im going to tell you, dont ever talk to your mother like that. You cant aight her or dismiss her.

She aint have a problem with it.

But I do, and I am a mother. So maybe she doesnt want to have that type of conversation with you, but I will. Dont you ever in your life, as long as Im in your space, talk to your mother like that.

Aight. Aight.

Malik! What did I just say?

Malik wasnt a bad kid or even a troublemaker; he was just always in trouble. It was heavy as he sat across from my desk and admitted he always failed, not least of all because this wasnt the first hard conversation he and I had had that week.

Two days earlier, I had let him know he wasnt going on the big Harvard trip with the rest of the school. In a much-publicized event, people from all over the world had funded the trip once they learned that there was a principal who wanted her underserved students to experience what it was like at one of Americas elite institutions of higher learning. Everyone at Mott Hall was excited beyond words to go, but Malik and a handful of other students wouldnt be invited to participate. He wasnt going because of his defiance toward adults, although he tried to argue, I can act right on a trip.

First, I told him, you have to remember that acting right starts in school. If you dont behave yourself here and respect the adults who love you, then you dont get the privilege of choosing when it will be convenient for you to do so. I dont prepare you for trips. I prepare you for life, I said. You need to identify how we can help you become the best scholar. Because if you think the only way of surviving life is going on a Harvard trip, then your priorities are not in the right place.

Now that he had come into my office to explain the source of his attitude and anger, I knew it was genuine. He wasnt trying to ingratiate himself, because Malik and all the kids at Mott Hall knew me better than that. My expectations are high and I never waver from them. He wasnt going on the trip, which hadnt been an easy decision for me. I didnt enter education to punish children.

In the last few days, though, something in Malik had clicked, a nebulous connection between attitude, trust, and opportunity. He was in my office to finally talk about what was keeping him from succeeding in school. This was a moment of great achievement, at least in my school.

By all accountseconomic, social, academicthe state of education in America for children of color living in disadvantaged communities is extremely poor, while the consequences for them if they dont make it in school are severe. Many issues contribute to the devastating difference between education for white children and education for those of color, including poverty, inequitable distribution of resources, and lower parental involvement and education levels. But the punitive way the system deals with children of color cant be underestimated.